Teacher Pages Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade

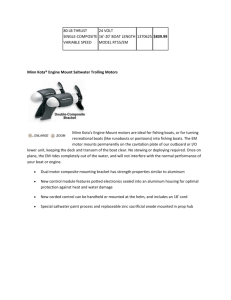

advertisement

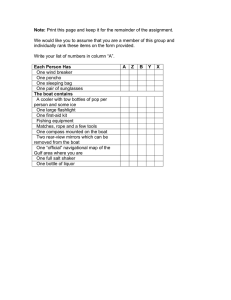

Teacher Pages Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Correlations to the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (6.2) Scientific processes. The student uses scientific inquiry methods during field and laboratory investigations. The student is expected to: (A) plan and implement investigative procedures including asking questions, formulating testable hypotheses, and selecting and using equipment and technology; (B) collect data by observing and measuring; (C) analyze and interpret information to construct reasonable explanations from direct and indirect evidence; (D) communicate valid conclusions; and (E) construct graphs, tables, maps, and charts using tools including computers to organize, examine, and evaluate data. (6.3) Scientific processes. The student uses critical thinking and scientific problem solving to make informed decisions. The student is expected to: (A) analyze, review, and critique scientific explanations, including hypotheses and theories, as to their strengths and weaknesses using scientific evidence and information; (C) represent the natural world using models and identify their limitations; (D) evaluate the impact of research on scientific thought, society, and the environment; and Purpose: The purpose of this lesson is to help students understand that intelligence is malleable and can be enhanced through thinking and working alone and in groups, participating in new activities, and engaging in problemsolving activities. Note: Text with a line through it indicates this part of the TEKS is not being addressed in this activity. Some TEKS statements printed here end with a ; or and and nothing thereafter— this indicates that further TEKS statements follow but are not included here. (6.4) Scientific processes. The student knows how to use a variety of tools and methods to conduct science inquiry. The student is expected to: (A) collect, analyze, and record information using tools including beakers, petri dishes, meter sticks, graduated cylinders, weather instruments, timing devices, hot plates, test tubes, safety goggles, spring scales, magnets, balances, microscopes, telescopes, thermometers, calculators, field equipment, compasses, computers, and computer probes; and Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 1 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Teacher Notes About the TEKS Students have been conducting investigations since they first entered kindergarten. Each year the level of complexity increases, so students in grade 6 should be able to collect data and draw conclusions based on their observations. Background Information for the Teacher Much research has examined the link between theories of intelligence (for example, the idea of intelligence as fixed versus malleable) and achievement, including significant research by Dr. Carol S. Dweck at Stanford University (see handout, Who Decides How Smart You Are?). Many people believe that intelligence is an innate and fixed trait that has little chance of being changed or increased. This belief in a fixed intelligence has contributed to a generation of students who do not see the value of participating in learning processes. The belief that they are not naturally smart results in a self-fulfilling prophecy of failure. On the other hand, students who believe that intelligence is not fixed—that if they work hard they can become smarter—are more willing to participate in new and challenging activities that lead to higher achievement levels. Problem-based inquiry is one way to give meaning to students’ work and help them see evidence that they can gain knowledge at levels higher than they may have previously believed. The Off to the Races activity is designed to engage students in a problem-based scientific inquiry that encourages them to use scientific process skills. As students work, they are guided through a series of steps that helps them build on their previous knowledge and learn new information as a result of their work. They have opportunities to design and implement their own experiment as part of a collaboration with classmates. Because this activity uses model boat-racing activities to show students how people work and learn, we provide links to some short video clips of a sailboat race to help capture the imagination of students who have not experienced sailing or sailboats. Resources American Psychological Association. (2003, May 28). Believing you can get smarter makes you smarter. Psychology Matters. www.psychologymatters.org/aronson.html. (Date retrieved: October 3, 2008). Spectacular sailing in the Northsea. video.google.com/videoplay?docid=8627961187760607213. (Date retrieved: October 3, 2008). Trei, L. Fixed versus growth intelligence mindsets: It’s all in your head, Dweck says. [News release]. Stanford University. www.stanford.edu/dept/news/pr/2007/pr-dweck-020707.html (Date retrieved: October 3, 2008). Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 2 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Purpose As a result of participating in this three-part activity, students will be able to • • • • follow a set of specific instructions to construct a paper boat that floats, work collaboratively to construct a boat that exceeds their original design, use electronic timers (stopwatches), and collect and record data to be used to construct a bar graph. Materials Fans with speed controls (2; must be identical) 1.5-m rain gutters with end caps (2) Water to fill rain gutters Large, stable table Stopwatches (2) Meter sticks (2) Blank transparencies Transparency-marking pen Chart paper for intelligence discussion Chart paper for bar graph Permanent marker (to label boats) Materials to Construct Boats Note: This activity takes place in three parts (that is, over three class days). For each part, the materials used to construct the boats vary. This list covers the materials for all three parts. Transparent tape Unlined copier paper (8½ in. x 11 in.; 5 sheets per team) Sticky notes 10-cm thin metal wire Unlined water-resistant paper (8½ in. x 11 in.; 2 sheets per student) Included in the Blackline Masters for This Activity Instructions for Folding a Paper Boat (1 copy for each student) Boat-Race Results Data Table (1 copy made into a transparency) Student pages (1 copy for each student) Who Decides How Smart You Are? (reading passage with questions; 1 copy for each student) Advance Preparation 1. Preview the video of a sailboat race from the link provided in the Resources section, or download your own. Such video clips are widely available on the web but must first be previewed because some have music that is not appropriate for the classroom. Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 3 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade 2. For each student, print one copy of the instructions for folding a paper boat. 3. Set up the gutters with the end pieces across the tops of three desks or chairs or, better, on a table large enough to support the entire gutter. 4. Mark one end of each gutter Start and the other end Finish. The two gutters are now your racecourse. 5. Fill each gutter with water until the water level is about 3 cm from the upper edge of the gutter. 6. Place one fan at the end of each gutter. Set the fan speed on low. 7. Assemble one paper boat as a model for students. 8. Make a transparency of the data table included in the blackline masters. Place the transparency on the overhead and provide a transparency-marking pen for students to use as they record the data collected throughout the activity. Note: Following are duplicates of the student pages for all three parts/days of this activity, with notes for the teacher in italics. Part 1 Read Before You Begin… What determines how smart you are? How do you know what you can and cannot do? These are very important questions to think about if you want to be successful in learning new things. Some people believe that everyone is born with a certain amount of intelligence and that nothing they do can increase their ability to understand the world around them and benefit from new experiences. Other people believe that the amount of intelligence each person possesses can increase depending on how much effort they put into learning. Objective This activity is designed to give you a chance to use knowledge that you already have, as well as information you just learned, to design a boat that is faster than the example boat. Give your best effort, and you will increase your knowledge of boat racing and better understand how people learn new things. Materials Fans with speed controls (2) 1.5-m rain gutters with end caps (2) Water Large, stable table Stopwatches (2) Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 4 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Meter sticks (2) Boat-Race Results Data Table on transparency Chart paper for intelligence discussion Chart paper for bar graph Instructions for folding a paper boat (1 copy for each student) Materials to Construct Boats Transparent tape Unlined copier paper (8½ in. x 11 in.; 5 sheets per team) Discussion introduction: Some of your students may never have seen a sailboat race. Use this as an opportunity to discover how much students already know about boats and their current attitudes about learning. The following questions will begin to engage students in a discussion that leads into this series of activities. Questions 1. How many of you have been on a sailboat or seen a sailboat race? How could you learn about a sailboat race if you have never had that opportunity? Play a few minutes of the sailboat racing video clip as a way to capture student interest and to inform students who have no previous knowledge of boat racing. 2. Watch the video of a boat race that your teacher plays for you. Now that you have had a chance to see a boat race, what do you now know about sailboat racing or sailboats that you did not know before? 3. How can new experiences help a person increase his or her knowledge? Record answers on a sheet of chart paper for future reference. 4. How does the amount of effort that you give a task affect how much you learn from the experience? Procedures 1. With a partner, follow the instructions for building a paper boat. Model how to fold the boat by having students make the folds at the same time that you make your folds. After this first folding, students should be able to fold their own boats, using the instructions for folding a paper boat. 2. When you have completed your boat, give it to your teacher, who will mix up the boats so each student team tests a boat different from the one it made. Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 5 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade As students place their boats in the designated area, check for any identifying marks on the boats. The students should not be able to identify which student folded the boat they will test. This helps students make more objective observations later. After you have checked the boats, place a number on the side of each boat for later use when students are collecting data. 3. You will use a stopwatch to determine how much time it takes a boat to travel to the finish. Let your teacher know if you need help using the stopwatch. Wait until the teacher gives the signal before you start the stopwatch. Once the test begins, continue timing the boat until it touches the Finish end of the gutter. Students may need to be shown how to operate the stopwatch. Start the Race 4. Place your boat in the gutter at the Start end. Place a meter stick across the racecourse in front of the boat. This keeps the boat in place until you are given the signal to release it. When you hear the signal, immediately lift the meter stick to allow the boat to begin its trip down the course. Stop the timer as soon as any part of the boat touches the Finish. 5. In the data table located on the overhead projector, record the amount of time it took the boat to reach the finish. Also record the amount of time on the bar graph that your teacher has posted in the room. Record your data beside the number that matches the number on the boat. As each team completes its race, it should record its boat’s time. After all boats have been timed, identify the boats with the fastest and slowest times. Ask students to compare the way the fastest and slowest boats were folded. Questions 1. All the boats were folded according to the same instructions. Why are their racing times not the same? 2. What can you identify on the boats that made some faster than others? As students examine the boats, record any differences they observe. Tell them they will use this information in the next portion of this activity, when they design their own boat. 3. How can asking questions help increase our knowledge about the world around us? Add their answers to the chart paper reserved for this purpose. Place the fastest and slowest boats in a place where they can dry out. You can dispose of the other boats or return them to the students. Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 6 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Part 2 Remind students that they are attempting to build a boat that is faster than the original design and that they are also learning how they can increase their knowledge of boat racing and how people learn. Use the fastest and slowest boats that you saved from Part 1 of this activity to again compare structural features (as you did at the end of the last class). Remind students that they have the opportunity to design a new boat to move across the water faster than the fastest boat in the first race. Review the comparisons they made while looking at the fastest and slowest boats to identify what made some faster than others. Ask them to suggest ways to make a new design that results in their new boat going faster than the original design. Write their design suggestions on chart paper. Questions Answers will vary. 1. How does sharing ideas help increase the probability that you can build a new boat that is faster than the ones used in the original test? 2. How does the amount of effort that you put into designing and building your boat determine how well it performs? 3. How does working with others and sharing ideas help increase your ability to do new tasks and learn about the world around you? Explain to students that they will now begin to design a boat that they believe will move across the water faster than the boat they previously used. Students are allowed to use any design that can be constructed from the items on the materials list. They may not use any materials that are not on the list. Materials Fans with speed controls (2) 1.5-m rain gutters with end caps (2) Water Large, stable table Stopwatches (2) Meter sticks (2) Boat-Race Results Data Table on transparency Chart paper for intelligence discussion Chart paper for bar graph Permanent marker (to label boats) Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 7 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Materials to construct boats Transparent tape Unlined copier paper (8½ in. x 11 in.; 5 sheets per team) Sticky notes 10-cm thin metal wire Procedures 1. Use the information that your class gathered about the boats used in the first test to draw a design for a boat that is faster than the fastest boat used in the first test. (Note: Do not build the boat yet!) You are allowed to design any type of boat that can be built with the materials on the list. You can change the design in any way that you believe makes the boat faster. To record your design, write the title Individual Boat Design on a blank piece of paper. On that sheet, make a sketch of your new design. Under your sketch, explain why you believe that your design will be faster than the fastest boat from the first test. Once everyone is done designing their individual boats, your teacher will divide you into teams for the next part of the activity. After students have designed their individual boats, divide the class into teams of three or four for the next part of the activity. 2. Share your boat design with your team. Circulate from team to team and listen to make sure that each student has the opportunity to share his or her design. 3. As a team, you can use only one design. On a blank piece of paper, write the title Team Boat Design. On that sheet, make a sketch of the boat design that the team decides to enter into the next test. Everyone must agree on this design, and it must include some part of each person’s individual design. Under the sketch, write down why this design was the one chosen by the group. Circulate from team to team to make sure that each new design has some element from each team member. 4. Show your team design to your teacher for final approval. Check the design to make sure that it can be made from the materials list and is likely to float. After approval, give the students the materials to construct their teams’ practice boats. Note: Give students only the materials on the list; do not give students the water-resistant paper until after their teams’ practice boats have been tested. 5. After you receive your construction materials, build a practice boat. Place your boat in the gutter racecourse and make sure that it remains upright and floats. Then make adjustments to the design as needed. This is just a test; do not race your boat yet! Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 8 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade At this point, students are only making sure that their boat remains upright in the water; they should not race their practice boats. 6. When you are satisfied with your design, build an identical boat for use in the final race. This time your boat will be built with water-resistant paper that your teacher gives you. Give each team water-resistant paper once the practice boats have been tested and refined if necessary. 7. Use a permanent marker to write your team name on your water-resistant boat and turn it in to your teacher. Questions Answers will vary. 1. How well did your team members share ideas with each other? 2. How can sharing ideas help make a design better? 3. How can sharing ideas help you learn about the world around you? Add these responses to the chart paper you have reserved for this purpose. Part 3 Remind students that they are attempting to build a boat that is faster than the original design and that they are also learning how they can increase their knowledge of boat racing and of how people learn. Post the time to beat in a very visible location in the room. This is the time recorded for the fastest boat in the first race. Record the results of this day’s races on the boat-race results data table on the transparency. Questions Answers will vary. 1. What is the advantage of using a boat that was designed by several people working together? 2. How is the method that you used to design the boat for this race similar to methods used by scientists when they are attempting to solve a problem? Hand back to each team of students their water-resistant boat made at the end of Part 2. Before beginning the time trials, remind students of how to use the stopwatch. One team at a time brings its boat to the racecourse. For this race, only one boat will be in the water at a time because today’s race is against the clock. Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 9 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Materials Fan with speed controls (1) 1.5-m rain gutter with end caps (1) Water Large, stable table Stopwatches (2) Meter stick (1) Boat-Race Results Data Table on transparency Chart paper for intelligence discussion Chart paper for bar graph Water-resistant team boats made in Part 2 of activity Procedures 1. When your team is called, take your boat to the racecourse. One person on the team explains your boat’s design to the class. 2. One member of the team then places the boat at the Start end of the racecourse. Place the meter stick across the racecourse to hold the boat in place until your teacher gives the signal to start. 3. Two members of your team use stopwatches to time the movement of your boat. Begin the timers when the start signal is given and continue until any part of the boat touches the Finish end of the gutter racecourse. Compare the times taken by both timers and take the average. 4. Record the time in the data table and graph your time on the bar graph. After all teams have timed their boats on the racecourse, instruct teams to discuss the results and answer the following questions. Arrange the boats on the racecourse table for students to examine. Questions Answers will vary. 1. Examine the boats that were faster than the original design and compare them to the boats that were slower than the original design. What do the faster boats have in common? What do the slower boats have in common? 2. Answer one of the following questions: a. If your boat moved across the water slower than the original design, what do you believe caused the boat to be slower? How can this knowledge help in the design of future boats? b. If your boat moved across the water faster than the original design, what do you believe caused it to be faster? How can this knowledge help in the design of future boats? Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 10 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade 3. What are some advantages of using models of boats before attempting to build a full-sized boat? 4. Read the passage from your teacher about how people learn (title: Who Decides How Smart You Are?). Discuss the questions at the end of the passage with your team and prepare to participate in a class discussion of your answers. Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 11 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Blackline Masters Contents Instructions for Folding a Paper Boat Boat-Race Results Data Table Student pages Who Decides How Smart You Are? (reading passage with questions) Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 12 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 13 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 14 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 15 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 16 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 17 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Boat-Race Results Data Table Boat Number Time Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 18 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Student Pages Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Part 1 Read Before You Begin… What determines how smart you are? How do you know what you can and cannot do? These are very important questions to think about if you want to be successful in learning new things. Some people believe that everyone is born with a certain amount of intelligence and that nothing they do can increase their ability to understand the world around them and benefit from new experiences. Other people believe that the amount of intelligence each person possesses can increase depending on how much effort they put into learning. Objective This activity is designed to give you a chance to use knowledge that you already have, as well as information you just learned, to design a boat that is faster than the example boat. Give your best effort, and you will increase your knowledge of boat racing and better understand how people learn new things. Materials Fans with speed controls (2) 1.5-m rain gutters with end caps (2) Water Large, stable table Stopwatches (2) Meter sticks (2) Boat-Race Results Data Table on transparency Chart paper for intelligence discussion Chart paper for bar graph Instructions for folding a paper boat Materials to Construct Boats Transparent tape Unlined copier paper (8½ in. x 11 in.; 5 sheets per team) Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 19 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Questions 1. How many of you have been on a sailboat or seen a sailboat race? How could you learn about a sailboat race if you have never had that opportunity? 2. Watch the video of a boat race that your teacher plays for you. Now that you have had a chance to see a boat race, what do you now know about sailboat racing or sailboats that you did not know before? 3. How can new experiences help a person increase his or her knowledge? 4. How does the amount of effort that you give a task affect how much you learn from the experience? Procedures 1. With a partner, follow the instructions for building a paper boat. 2. When you have completed your boat, give it to your teacher, who will mix up the boats so each student team tests a boat different from the one they made. 3. You will use a stopwatch to determine how much time it takes a boat to travel to the finish. Let your teacher know if you need help using the stopwatch. Wait until the teacher gives the signal before you start the stopwatch. Once the test begins, continue timing the boat until it touches the Finish end of the gutter. Start the Race 4. Place your boat in the gutter at the Start end. Place a meter stick across the racecourse in front of the boat. This keeps the boat in place until you are given the signal to release it. When you hear the signal, immediately lift the meter stick to Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 20 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade allow the boat to begin its trip down the course. Stop the timer as soon as any part of the boat touches the Finish. 5. In the data table located on the overhead projector, record the amount of time it took the boat to reach the finish. Also record the amount of time on the bar graph that your teacher has posted in the room. Record your data beside the number that matches the number on the boat. Questions 1. All the boats were folded according to the same instructions. Why are their racing times not the same? 2. What can you identify on the boats that made some faster than others? 3. How can asking questions help increase our knowledge about the world around us? Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 21 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Part 2 Questions 1. How does sharing ideas help increase the probability that you can build a new boat that is faster than the ones used in the original test? 2. How does the amount of effort that you put into designing and building your boat determine how well it performs? 3. How does working with others and sharing ideas help increase your ability to do new tasks and learn about the world around you? Materials Fans with speed controls (2) 1.5-m rain gutters with end caps (2) Water Large, stable table Stopwatches (2) Meter sticks (2) Boat-Race Results Data Table on transparency Chart paper for intelligence discussion Chart paper for bar graph Permanent marker (to label boats) Materials to construct boats Transparent tape Unlined copier paper (8 ½ in. x 11 in.; 5 sheets per team) Sticky notes 10-cm thin metal wire Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 22 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Procedures 1. Use the information that your class gathered about the boats used in the first test to draw a design for a boat that is faster than the fastest boat used in the first test. (Note: Do not build the boat yet!) You are allowed to design any type of boat that can be built with the materials on the list. You can change the design in any way that you believe makes the boat faster. To record your design, write the title Individual Boat Design on a blank piece of paper. On that sheet, make a sketch of your new design. Under your sketch, explain why you believe that your design will be faster than the fastest boat from the first test. Once everyone is done designing their individual boats, your teacher will divide you into teams for the next part of the activity. 2. Share your boat design with your team. 3. As a team, you can use only one design. On a blank piece of paper, write the title Team Boat Design. On that sheet, make a sketch of the boat design that the team decides to enter into the next test. Everyone must agree on this design and it must include some part of each person’s individual design. Under the sketch, write down why this design was the one chosen by the group. 4. Show your team design to your teacher for final approval. 5. After you receive your construction materials, build a practice boat. Place your boat in the gutter racecourse and make sure that it remains upright and floats. Then make adjustments to the design as needed. This is just a test; do not race your boat yet! 6. When you are satisfied with your design, build an identical boat for use in the final race. This time your boat will be built with water-resistant paper that your teacher gives you. 7. Use a permanent marker to write your team name on your water-resistant boat and turn it in to your teacher. Questions 1. How well did your team members share ideas with each other? Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 23 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade 2. How can sharing ideas help make a design better? 3. How can sharing ideas help you learn about the world around you? Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 24 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Part 3 Questions 1. What is the advantage of using a boat that was designed by several people working together? 2. How is the method that you used to design the boat for this race similar to methods used by scientists when they are attempting to solve a problem? Materials Fan with speed controls (1) 1.5-m rain gutter with end caps (1) Water Large, stable table Stopwatches (2) Meter stick (1) Boat-Race Results Data Table on transparency Chart paper for intelligence discussion Chart paper for bar graph Water-resistant team boats made in Part 2 of activity Procedures 1. When your team is called, take your boat to the racecourse. One person on the team explains your boat’s design to the class. 2. One member of the team then places the boat at the Start end of the racecourse. Place the meter stick across the racecourse to hold the boat in place until your teacher gives the signal to start. 3. Two members of your team use stopwatches to time the movement of your boat. Begin the timers when the start signal is given and continue until any part of the Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 25 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade boat touches the Finish end of the gutter racecourse. Compare the times taken by both timers and take the average. 4. Record the time in the data table and graph your time on the bar graph. Questions 1. Examine the boats that were faster than the original design and compare them to the boats that were slower than the original design. What do the faster boats have in common? What do the slower boats have in common? 2. Answer one of the following questions: a. If your boat moved across the water slower than the original design, what do you believe caused the boat to be slower? How can this knowledge help in the design of future boats? b. If your boat moved across the water faster than the original design, what do you believe caused it to be faster? How can this knowledge help in the design of future boats? Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 26 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade 3. What are some advantages of using models of boats before attempting to build a full-sized boat? 4. Read the passage from your teacher about how people learn (title: Who Decides How Smart You Are?). Discuss the questions at the end of the passage with your team and prepare to participate in a class discussion of your answers. Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 27 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Who Decides How Smart You Are? Have you ever wondered why some people seem to be smarter than other people? If you have, you are not the only one. Professor Carol Dweck has been studying how people learn and has made some interesting discoveries. She found that people generally have one of two beliefs. Some people believe that individuals are born with a set or fixed intelligence and that as they grow up, they will be “stuck” within the limits of the abilities they were born with. Other people believe that individuals are not limited by the abilities they were born with. They believe that a person’s intelligence can be increased by hard work and determination. To find out which of these beliefs is more accurate, Professor Dweck did an experiment using two groups of seventh-grade students. She gave Group One information explaining that how well a person learns depends not only on their natural abilities, but also on hard work and a desire to learn. Group One was also taught study skills. Group Two was taught study skills, but Professor Dweck did not give this group information about things that affect how well a person learns. After eight weeks, the professor measured the learning progress of Group One and Group Two. It turned out that the students in Group One performed at much higher levels than the students in Group Two. Professor Dweck concluded that students who believed that they could learn to be smarter were more willing to try new things and worked harder. Other experiments showed similar results. Professor Dweck concluded that people who think they can increase their intelligence and learn new things usually work harder and do better in school. On the other hand, people who think they are “stuck” with the intelligence they were born with are not as willing to try new things and do not work as hard. Because of this belief, they do not do as well in school. Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 28 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Based on this reading and what you have experienced as a student, discuss the following situations. 1. A student was unable to correctly answer a question he was asked during class. Some of the students in the class laughed at him and now he is no longer willing to answer any questions because he felt dumb. Discuss some events that you believe can make a person feel “smart” and some events that you believe can make a person feel “dumb.” 2. If a person has to work hard to learn new information, should that person be considered intelligent? Explain your answer. 3. When you learned how to ride a bike, you may have fallen several times before successfully riding the bike. How is learning new information similar to learning how to ride a bicycle? 4. How can new experiences help a person increase their knowledge? Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 29 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade 5. How does the amount of effort that you apply to a task affect how much you learn from the experience? 6. If someone believes he or she can increase intelligence, he or she is more likely to be successful and is more willing to try new activities. Explain why this is true. 7. Now that you have had a chance to view a boat race, build a boat, and participate in a boat race, what do you know about sailboat racing or sailboats that you did not know before? Has your intelligence increased? 8. Are you smarter than you were when you started this activity? Explain your answer. Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 30 Off to the Races: How People Work and Learn—Sixth Grade Resources Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. Dweck, C. S. (2002). Messages that motivate: How praise molds students’ beliefs, motivation, and performance (in surprising ways). In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement. New York: Academic Press. Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-Theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis/Psychology Press. Charles A. Dana Center at The University of Texas at Austin November 2008 31