Document 11663910

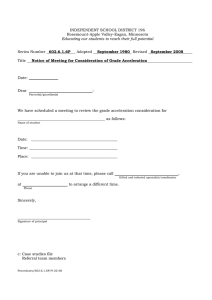

advertisement