THE SCHOOLS THE TALIBAN WON'T TORCH....

advertisement

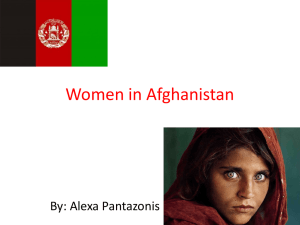

THE SCHOOLS THE TALIBAN WON'T TORCH.... December 18, 2007 Kevin Drum The Taliban has been increasingly resurgent in Afghanistan over the past year, but our problems there go well beyond the military. The Washington Post reported on Monday that "Afghanistan is so poor and so starved for modern infrastructure, one senior administration official said, that it could well be 'a longer, if not larger, challenge than Iraq.'" A day earlier, the New York Times reported that Nicholas Burns, the under secretary of state for political affairs, "was coordinating another internal assessment of diplomatic efforts and economic aid — the sorts of 'soft power' assistance beyond combat force that officials agree are required for success." In the December issue of the Monthly, Gregory Warner says a big part of the soft-power problem is simple funding: "According to the RAND Corporation, the American-led nation-building effort in Afghanistan is the least-financed such effort in sixty years." The solution, though, isn't just more funding, but funding the right kind of programs: In a country where almost all the recent news has been bad news, the National Solidarity Program, or NSP, offers a rare glimmer of hope....The novel thinking behind the National Solidarity Program is largely the work of Scott Guggenheim, a maverick World Bank staffer who in the late 1990s pioneered a similar program in Indonesia. ....Guggenheim designed a program that would distribute small grants to villages....Local leaders were charged with administering the projects and required to take bookkeeping classes and keep minutes at planning meetings. Billboards above project sites indicated how money had been spent, encouraging local oversight. "The core elements were requiring that citizens participate and that there be high levels of transparency about how money was being transferred and used," one of Guggenheim's former Bank colleagues, Dennis de Tray, now at the Center for Global Development in Washington, said. "It had to be auditable." ....Maybe the most surprising characteristic of NSP projects is security related. In a survey last year of school burnings by the Taliban, Human Rights Watch observed that schools built by the NSP have less chance of being destroyed by insurgents than schools built by other aid programs. The reason, as Dennis de Tray explains, relates to the matter of local ownership. "If you're the Taliban, you feel some comfort in attacking things built by foreigners," de Tray says. "But you don't want to create animosity among citizens you're trying to recruit to your side." The NSP has other benefits as well: village councils that successfully complete projects can apply for additional grants, and after the fourth or fifth grant cycle, Guggenheim says, "something like real responsive government started to emerge." Unfortunately, although other countries have increased their funding of NSP, the United States has actually decreased its contribution. The result is fewer villages participating, and fewer of them getting to the stage where the grants start to produce real changes in the way local governments become more responsible, more closely aligned with the central government, and less vulnerable to the Taliban. And the savings involved? A tiny fraction of what we spend on military and counternarcotics efforts. Read comments about the article