Albanian Phraseology in Its Narrow and Broad Sense Harallamb Miçoni

advertisement

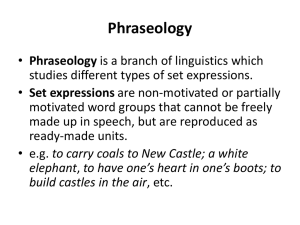

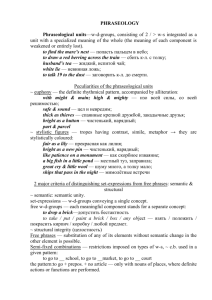

ISSN 2239-978X ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Social Research MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol. 4 No.4 June 2014 Albanian Phraseology in Its Narrow and Broad Sense Harallamb Miçoni Faculty of Education and Social Sciences, Department of Foreign Languages University of Gjirokaster, Albania Email : miconisllambi@yahoo.gr Leonard Rapi Faculty of Education and Social Sciences, Department of Foreign Languages University of Gjirokaster, Albania Email : nardirapi@yahoo.com Doi:10.5901/jesr.2014.v4n4p338 Abstract Besides phraseology in a narrow sense there is also another type of phraseology that we accept and which we propose for the Albanian language as well. It is phraseology in the broad sense which does not exclude phraseology in the narrow sense, but includes it as one of its main categories. By phraseology in the narrow sense we mean phraseology that studies phrasemes below the sentence level. By phraseology in the broad sense we mean phraseology that studies phrasemes up to the sentence level, such as proverbs and phraseological conversation formulae. The distinguishing condition of phraseology in the broad sense from phraseology in the narrow sense is sentence equivalence, a conception that most European phraseology researchers agree on today. The determining criteria we propose for phraseology in the broad sense as well as for phraseology in the narrow sense is non-literal referentiality, which means that the constituents of a phraseological sequence have lost their literal meanings and the phraseological sequence has a transferred meaning. It doesn’t matter how many words with a transferred meaning there are within a fixed phraseological multi-word sequence; even a single word with a transfeered meaning can change the meaning of a fixed multi-word combination, such as jetë qeni (dog’s life), thyej rekordin (break a record), mjaltë i ëmbël (lit. honey sweet, for very sweet), pendë i lehtë (lit. feather light, for very light), çelës anglez (lit. English key, for adjustable wrench), etc. Keywords: Phraseology, word equivalence, sentence equivalence, non-literal referentiality, figurativeness, semantic noncompositionality, collocational structure. 1. Distinguishing Condition of Phraseology in the Broad Sense from Phraseology in the Narrow Sense Phraseology began its life at the beginning of the 20-th century with its founder Charles Bally in 1909, whereas the first who studied it within the framework of the independent linguistic discipline was Russian linguist Vinogradov in 1947. As far as phraseology of the Albanian language is concerned, the first who studied it from the perspective of the linguistic science is Jani Thomai. In “Issues of the phraseology of the Albanian Language” (Çështje të frazeologjisë së gjuhës shqipe, alb.) (1981), Thomai defines phraseology as “the totality of those set word combinations, which have been formed historically and which have been crystallized as an indivisible unit and which are equivalent to a single word according to their categorical meaning”. Whereas in “The phraseological dictionary of the Albanian Language” (Fjalori frazeologjik i gjuhës shqipe, alb.) (1999), as far as phraseological units are concerned the author states that “in the field of the Albanian language we consider as general features of phraseological units the structure of the content-word group, semantic unit, stability, figurativeness, the neutralization of internal syntactic relations, word equivalence from the perspective of categorical meaning and function in discourse”. According to the features and criteria such as word equivalence, whole single meaning, figurativeness, stability, etc. that the author uses and according to the examples he offers, the type of phraseology the author deals with is phraseology in a narrow sense. There are also other linguists who study phraseology in a narrow sense. Thus, Vinogradov “restricts phraseological unit to more metaphorical items”1. “He and Amosova are at the foundations of a view of phraseology that restricts the scope of the field to a specific subset of linguistically defined multiword units”2. Moon, R. (1998). Fixed Expressions and Idioms in English. A Corpus-based Approach. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Granger, S. & Paquot, M. (2008). Disentangling the phraseological web, Granger, S. & Meunier, F. Phraseology -An interdisciplinary perspective. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia. 1 2 ̱͵͵ͺ̱ ISSN 2239-978X ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Social Research MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol. 4 No.4 June 2014 By phraseology in the narrow sense Burger et al. (2007) mean the study of units “shorter than the sentence”. This definition suits best vinogradovian phraseology in which are also included “phraseological combinations”3 as phrase-like phrasemes4. According to Burger et al’s definition, even Albanian phraseology represented by Thomai is phraseology in the narrow sense, but it is narrower than vinogradovian phraseology, because it has as its object of study only set multiword sequences equivalent to a single word and not just shorter than the sentence. For Thomai and the majority of traditional authors who support phraseology in the narrow sense, its object of study are word equivalent phrasemes, e.g. i kthej krahët (lit. turn ones back to sb, for abandon sb), i fërkoj krahët (lit. to rub sb’s back, for to flatter sb) vret miza (lit. he/she kills flies, for he/she does nothing), s’e mbyll gojën (lit. he/she doesn’t shut up his/her mouth, for he/she doesn’t stop speaking), s'lë dy gurë bashkë (lit. he/she doesn’t leave two stones together, for he/she is mischievous), etc. which are used in discourse as word equivalents, as single parts of sentences. Besides phraseology in the narrow sense that deals with the study of word equivalent units or units under the level of a sentence, there is also phraseology in a broader sense which we accept and propose for the Albanian language as well. By phraseology in the broad sense we mean the phraseology that studies phrasemes5 up to the sentence level, i.e. even the sentence units, such as proverbs and phraseological conversation formulae, e.g. Peshku në det, tigani në zjarr! (lit. The fish in the see, the frying pan at fire, for First catch the fish then fry it!) Ujët fle, hasmi s’fle! ( lit. Water sleeps, enemies don’t, for One has always to be vigjilent against one’s enemies!). Ju lumshin këmbët! (lit. Bravo to your legs, for Welcome!) Edhe njëqind (vjeç)! (lit. Another hundred (years), for Live to be a hundred!), etc., and in which we include word equivalent phrasemes as well. As far as this type of phraseology is concerned, Burger et al. (2007) claim that “they have the characteristics of the sentence” and they include in them “collocations, proverbs and formulae”. Consequently, the distinguishing condition of phraseology in the broad sense from phraseology in the narrow sense is sentence equivalence, “a conception that most European phraseology researchers agree on today”6. As Burger et al. (2007) point out “it can no longer be denied that proverbs possess important phraseological characteristics”. But phraseology in the broad sense doesn’t exclude phraseology in the narrow sense; it includes the latter as one of its main categories. Even that distinction between the units below the sentence level or equivalent to a single word and the sentence equivalent units was first made by Russians. “One of the first Russian phraseologists to refer to this distinction was Chernuisheva (1964), whose sentence-like units (called 'phraseological expressions') included sayings and familiar quotations.”7. But not all postvinogradovian researchers think that proverbs must be studied together with phraseological expressions. Thus, J. Casares (1950 ), N. N. Amosova (1963), J. Thomai (1981), etc., think that if the multi-word units do not constitute part of the sentence it is wrong to include them in the system of the language, because they are independent units of communication. But the above distinction was recognized and followed by other specialists of the linguistic field, such as Cowie (1988), Mel'þuk (1988), Glaser (1988) and Burger (1988) and later by Granger & Paquot (2008), etc. Even our opinion about the basic unit and the object of phraseology is not related to word equivalence, but it goes up to the sentence level (see Piirainen, 2008; cf. Thomai, 1981), because, as we’ll see in the case of studying proverbs as a particular phraseological category, before they (proverbs) are units of folklore, they are language sentence-like units. But how broad is phraseology in the broad sense? Concerning phraseology in the broad sense, some linguists have a much broader concept. They decide on the fate of the phraseological fixedness of some multi-word combinations through the language analysis based on the electronic text corpus. Thus, phraseology begins to be studied on the base of electronic text corpus by Halliday (1966), has as its main representative Sinclair (1991) and is followed by other linguists as well, such as Wray (2002). It is mentioned as a statistics- and frequency-based approach and uses the text corpus to identify lexical associations. This inductive approach offers a wide range of word combinations that do not fit our phraseological linguistic volume. Representatives of this approach don’t deal with the distinction between categories and subcategories of word combinations. According to them, phraseological expressions take priority over words. They think that even free word combinations have a place in phraseology. Sinclair's (2008) last slogan is: “The phrase, only the Vinogradov V. V. (1947). ‘Ob osnovnyx tipach frazeologiþeskix edijic v sovremennom russkom jazyke’. In: V. V. Vinogradov, Izbrannyje trudy: leksikologija i leksikografija. Moskva: Nauka. 4 Phraseme is the general term we use for any phraseological set word combination and it corresponds to the terms phraseological fixed expressions, phraseological unit, set phrases, etc., used by different researchers. See also below. 5 Phraseme is the general term we use for any phraseological set word combination and it corresponds to the terms phraseological fixed expressions, phraseological unit, set phrases, etc., used by different researchers. See also below. 6 Piirainen, E. (2007). Figurative phraseology and culture. Granger, S. & Meunier, F. Phraseology -An interdisciplinary perspective. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia. 7 Cowie, A. P. (1998). Phraseology: Theory, Analysis, and Applications, (Oxford Studies in Lexicography and Lexicology) Oxford: Oxford University Press. 3 ̱͵͵ͻ̱ ISSN 2239-978X ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Social Research MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol. 4 No.4 June 2014 phrase, nothing but the phrase”. This very broad view is related to the treatment of phraseology according to the text corpus frequency which is not a condition for the formation of phraseological expressions or phrasemes. We agree with Gaatone (1997) who criticizes Sinclair's radical view and who warns that not everything can be considered phraseological. Our non-approval of this comprehensive attitude is related to the purpose of studying phrasemes by phraseology, which doesn’t concern all set syntactic word combinations. If phrasemes were studied only for their special (set) syntactic relation, it would not be necessary for them to be studied by another branch, e.g. phraseology, but they would be studied by syntax itself, because, as Thomai (2006) notes in relation with the phraseological units of the Albanian language, they are “content-word groups” “which have the same grammatical relations as free content-word groups (determinative, objective, circumstantial, etc.)”, although “in phraseological units syntactic relations are not always so clear as in free word combinations”. Phrasemes are studied by the special branch of phraseology because of the transferred (new) meaning of the whole set word combination or at least of one of the constituents of the set word combination, i.e. of a transferred (new) meaning conditioned by and limited within this set word combination. This is the reason why phrasemes were initially studied in the field of lexicology and specifically by Bréal (1897) for their semantic aspect and by Bally (1909) for their stylistic aspect. According to Bally (1909, as quoted by Symeonidis (ȈȣȝİȦȞȓįȘȢ, gr.), 2000) “the essence of phraseologisms lies in their semantic nature”. This is also the reason why our phraseology in the broad sense doesn’t consider phraseological the word combinations based on the frequency of co-used words (Cf. Sinclair, 1991), as well as it doesn’t consider phraseological all the fixed word combinations, such as artesian well, the cat mews (Cf. Mel’þuk, 1998), despite the fact that the associative unique combination of the word artesian with the word well is not different from the combination of the word bucket only used with the word kick in the idiom kick the bucket. It considers phraseological only the set word combinations that have a transferred (new) meaning. 2. Determining Criterion of Phraseology in the Broad and Narrow Sense As regards phraseology in the narrow sense, we can say that different authors base it on different criteria. Thus, a lot of phraseologists, such as Thomai and Smirnitsky, apply the criterion of semantic non-compositionality or the whole meaning of set sequences, the criterion of word equivalence and the criterion of figurativeness and they limit phraseological expressions to the figurative language units equivalent to a single word, whereas Vinogradov limits phraseological expressions only to the most figurative language units, and, therefore, accepts the criterion of semantic compositionality, e.g. meet the needs (Vinogradov, 1947, as quoted by Cowie, 1998) or pres ditën e dasmës (lit. to cut the wedding day), where pres (cut) is used figuratively, whereas ditën e dasmës (wedding day) is used in the literal meaning, and which both enter the discourse with their independent meanings, and, consequently, the meaning of the sequence is compositional. Even as regards phraseology in the broad sense, linguists have different opinions. Thus, for Jean-Pierre Colson (2008), “phraseology in the broad sense meets the criterion of polylexicality and stability, whereas phraseology in the narrow sense requires the additional criterion of non-compositionality“. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (1979) is one of the first works that talks about two types of phraseology as well as criteria. According to the encyclopedia, the object of phraseology is narrow when phraseological expressions are defined by the criteria of semantic unit of the word group’s meaning and the equivalence of the word group’s equivalence to a single word in terms of denominative function. Whereas phraseology in the broad sense is defined by the criterion of regular usage in a fixed form, independently of the semantic unit of the word group or or of the word group’s divisibility into the meanings of its constituent words. Even Symeonidis, (2000) talks about two types of phraseologies and their respective criteria. According to him phraseology in the narrow sense “is a branch of linguistics that studies set language word combinations which have the function and the value of a single word in a sentence” and it is determined on the basis of the criteria of noncompositionality and figurativeness, whereas phraseology in the broad sense is determined on the basis of the criteria of stability and, partly, non-compositionality. As far as the determining criterion of phraseology in the broad sense is concerned, we think that none of the above criteria proposed for phraseology in the narrow sense, such as word equivalence, semantic non-compositionality, figurativeness, etc., is a determining criterion for phraseology in the broad sense, but they are distinguishing criteria of particular phraseological categories within phraseology in the broad sense. We don’t even agree only with the criterion of stability proposed for phraseology in the broad sense by the above authors. The determining criterion we propose for phraseology in the broad sense is non-literal referentiality which means that the constituents of the sequence have lost their literal meanings and that the sequence has a transferred meaning, because phrasemes are studied for their (new) ̱͵ͶͲ̱ ISSN 2239-978X ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Social Research MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol. 4 No.4 June 2014 transferred meaning which is restricted within a fixed syntactic word combination. The essence of phrasemes lies in their semantic nature, that is why they are studied within the framework of lexicology. We would propose the same criterion for phraseology in the narrow sense, and, consequently, we would enlarge the volume of Albanian phraseology in the narrow sense by compositional, non-word-equivalent phrasemes (see below for additional information), e.g., jetë qeni (dog’s life), çelës anglez (lit. English key, for adjustable wrench), thyej rekordin (break a record), borë i bardhë (lit. snow white, for very white), etc., as well as by non-figurative (non-compositional) phrasemes, e.g., drita e kuqe (red light), dërrasë e zezë (black board), etc. We can so come to the conclusion that the general criterion for phraseology in the narrow sense will be non-literal referentiality, whereas its distinguishing condition from phraseology in the broad sense will be the equivalence to the units below the sentence level. 3. Phrasemes with a Collocational Structure as Part of Phraseology in the Broad and Narrow Sense It doesn’t matter how many words with a transferred meaning exist within a phraseme or a phraseological fixed multiword combination; even a single word with a transferred meaning can divert the meaning of a fixed multi-word combination, e.g., jetë qeni, thyej rekordin, mjaltë i ëmbël, çelës anglez, etc. This idea is also supported by Kunin (1970) who, following the criterion of figurativeness proposed by Vinogradov, besides full figurativeness in phrasemes or phraseological units as he calls his examples, proposes the concept of partial figurativeness. According to him, “a phraseological unit […] is a stable word-group characterized by a completely or partially transferred meaning”, such as kick the bucket with a fully transferred meaning, or Greek gift with a partially transferred meaning, which are some of the examples he proposes. The words with a transferred or figurative meaning obtain these meanings only as part of the phrasemes, and for this reason we’ll call them “idiomatic words”8. As Riehemann (2001) says, “the word miss in miss the boat has the same meaning it has in other word combinations, that is why it is not an idiomatic word, whereas the word combination miss the boat is an phraseme with a partially transferred meaning, i.e. only of the idiomatic word boat”. The words that are not idiomatic have a literal meaning they preserve even in the phraseme. This literal meaning plays a role in the phraseme; it has a selective, collocational role without which there would be no phraseme. Consequently, in order to obtain the meaning of the phraseme, it is sufficient to have even a single idiomatic word that doesn’t have the meaning it can have outside the phraseme. We’ll call this phraseme a phraseme with partial figurativeness and its meaning is deferred from the meanings of its constituents, e.g. jetë qeni (dog’s life) = a very bad life, uri ujku (wolf’s hunger) = very big hunger, humbas trenin (lit. miss the train) = miss the chance, çelës anglez (lit. English key) = a kind of key, kafe turke (lit. Turkish coffee) = a kind of coffee, thyej rekordin (break a record) = to achieve a better result, borë i bardhë (lit. snow white) = very white, etc., i.e. which are constructed on the basis of semantic compositionality as the sum of the meanings of their constituents. In these cases one word preserves its literal meaning, whereas only the other word has obtained a figurative meaning, and, consequently, both of them have transparent meanings and the sequence is collocational. The inclusion or not of phrasemes with a collocational structure in phraseology constitutes the weakest and most controversial point for the two types of phraseologies. By sanctioning non-compositionality and mainly word-equivalence as central features of phraseology, traditional phraseology in the narrow sense has focused its attention on idioms, whereas phraseology in the broad sense on proverbs at the expense of those more variable word combinations (phrasemes with a partially transferred meaning or with a collocational structure), which, as they are considered less “central”, tend to be treated less. These sequences, considered as peripheral or left outside the borders of phraseology either by the authors of phraseology in the narrow sense, such as Smirnitsky, 1995, Thomai, 1981, or by the authors of phraseology in the broad sense, such as Alexander, 1878, are being included more and more in the phraseological volume of authors such as Vinogradov, Cowie, Moon, granger, Burger, etc. Depending on the inclusion or not of phrasemes with a partially transferred meaning or with a collocational structure in the phraseology in the narrow sense, we can say that the phrasemes of phraseology in the narrow sense vary from word equivalent combinations (see Smirnitsky, Thomai) to phrase equivalent combinations (see Vinogradov), whereas phraseology in the broad sense includes in most cases both of the above types of word combinations, but, besides them, it also includes sentence equivalent combinations which constitute its object of study par excellence. 4. The Importance of Studying Albanian Phraseology in the Broad Sense The importance of studying phraseology in the broad sense lies in a theoretical level as well as in a practical level. 8 Riehemann, S. (2001), A Constructional Approach to Idioms and Word Formation, PhD thesis, Stanford University. ̱͵Ͷͳ̱ ISSN 2239-978X ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Social Research MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol. 4 No.4 June 2014 The study of phraseology in the broad sense in the theoretical level is important because: It helps to revise phraseology according to more comprehensive criteria such as sentence equivalence and nonliteral referentiality. It helps to determine the limits between what is phraseological and what is non-phraseological. It may help to better know the nature of phrasemes, the nature of the figurative language, and the nature of the language itself. The study of phraseology in the broad sense in the practical level is important because: It helps to determine the phraseological volume, because there are a lot of multi-word units that have not found the place they belong to in Albanian phraseology. It is about including in phraseology proverbs and phraseological conversation formulae, e.g. Peshku në det, tigani në zjarr! Ujët fle, hasmi s’fle! and also the proper phraseological collocations, e.g. korr fitore, pendë i lehtë, or other phrasemes with a collocational structure, e.g. jetë qeni (dog’s life), çelës anglez (lit. English key, for adjustable wrench) As a consequence, phraseology in the broad sense “is an adequate and realistic description of phraseological extent”9. It serves the systemizing of phrasemes in lexicographical works. It helps to compile special dictionaries and to create special computer programmes. It serve the translation from Albanian into a foreign language and vice versa and mainly the computer models of automatic translation. It serves the teaching practice about the compilation of texts for the teaching of Albanian as a foreign language in which phrasemes should be included as part of metaphorical and cultural learning. The accurate acquisition of phrasemes helps the students to appear as language native speakers. It serves the teaching of phrasemes not only to foreign students who learn Albanian, but also to those who have Albanian as their mother tongue. This means that phrasemes are important even during the use by the speakers of the Albanian language themselves as far as its semantic and morpho-semantic particularities are concerned. 5. Conclusions Besides phraseology in its narrow sense there is also another type of phraseology that we accept and propose for the Albanian language as well. It is phraseology in the broad sense which does not exclude phraseology in the narrow sense, but includes it as one of its main categories. By phraseology in the broad sense we mean phraseology that studies phrasemes up to the sentence level, such as proverbs and phraseological conversation formulae. Consequently, the distinguishing condition of phraseology in the broad sense from phraseology in the narrow sense is sentence equivalence, a conception that most European phraseology researchers agree on today. The determining criterion we propose for phraseology in the broad sense as well as for phraseology in the narrow sense is non-literal referentiality, which means that the constituents (or at least one of them) of a phraseological sequence have lost their literal meanings and that the phraseological sequence has a transferred meaning. It doesn’t matter how many words with a transferred meaning exist within a phraseme; even a single word with a transferred meaning can divert the meaning of a multi-word combination from a free sequence to a phraseological fixed sequence. References Amosova, N. N. (1963). Osnovy Anglijskoj Frazeologii, Leningrad: Nauka. Bally Ch. (1909). Traité de stylistique française. Paris : Klincksieck. Bréal, M. (1897). Essai de sémantique. Hachette, Paris. Burger, H. (1998) Phraseologie: Eine Einführung am Beispiel des Deutschen, Berlin: Erich Schmidt. Burger, H., D. Dobrovol’skij, P. Kühn & N. R. Norrick (eds.) (2007) Phraseology: An International Handbook of Contemporary Research, vols 1 & 2. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Casares, J. (1950). La locución, la frase proverbial, el refrán y el modismo, in Introducción a la lexicografía moderna, Madrid, Aguirre, 1950. Chernuisheva, I. I. ( 1964), Die Phraseologie der gegenwärtigen deutschen Sprache ( Moscow: Vuisshaya Shkola). Colson, J.-P. (2008). Cross-linguistic phraseological studies: An overview. Granger, S. & Meunier, F. Phraseology -An interdisciplinary perspective. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia. Häcki-Buhof, A. (2007). Psycholinguistic aspects of phraseology: European tradition Burger, H., D. Dobrovol’skij, P. Kühn & N. R. Norrick (eds.) Phraseology: An International Handbook of Contemporary Research, vols 1 & 2. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 9 ̱͵Ͷʹ̱ ISSN 2239-978X ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Social Research MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol. 4 No.4 June 2014 Cowie, A. P. (1988). Stable and creative aspects of vocabulary use. In Carter, R. & M. J.McCarthy (eds.) Vocabulary and Language Teaching. London: Longman. Cowie, A. P. (1998). Phraseology: Theory, Analysis, and Applications, (Oxford Studies in Lexicography and Lexicology) Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gaatone, D. (1997). La locution: Analyse interne et analyse globale. In Martins-Baltar, M. (ed.) La locution entre langue et usages, 165– 177. Fontenay-Saint Cloud: ENS éditions. Gläser, R. (1988) The grading of idiomaticity as a presupposition for a taxonomy of idioms. In Hüllen, Werner & Schulze, Rainer (Eds.) Understanding the Lexicon, Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. Granger, S. & Paquot, M. (2008). Disentangling the phraseological web, Granger, S. & Meunier, F. Phraseology -An interdisciplinary perspective. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia Granger, S. & Paquot, M. (2008). Disentangling the phraseological web, Granger, S. & Meunier, F. Phraseology -An interdisciplinary perspective. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia. Häcki-Buhof, A. (2007). Psycholinguistic aspects of phraseology: European tradition Burger, H., D. Dobrovol’skij, P. Kühn & N. R. Norrick (eds.) Phraseology: An International Handbook of Contemporary Research, vols 1 & 2. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Halliday, M. A. K. (1966). Lexis as a linguistic level. In Bazell, C. E., J. C. Catford, M. A. K. Halliday & R. H. Robins (eds.) In Memory of John Firth, 148–162. London: Longman. Kunin, A.V. (1970): Anglijskaja frazeologija. Teoreticeskij kurs. Moscow : Vyssaja Skola Mel’þuk, I. (1998). Collocations and Lexical Functions. In: A.P. Cowie (ed.), Phraseology. Theory, Analysis, and Applications, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Mel’þuk, I. (1998). Collocations and Lexical Functions. In: A.P. Cowie (ed.), Phraseology. Theory, Analysis, and Applications, Oxford: Clarendon Press. MEL’ýUK, I. et al. (1988) : Dictionnaire explicatif et combinatoire du français contemporain. Recherches lexico-sémantiques II, (DECFC), Montréal, PUM. Moon, R. (1998). Fixed Expressions and Idioms in English. A Corpus-based Approach. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Piirainen, E. (2007). Figurative phraseology and culture. Granger, S. & Meunier, F. Phraseology -An interdisciplinary perspective. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia. Piirainen, E. (2008). Figurative phraseology and culture. Granger, S. & Meunier, F. Phraseology -An interdisciplinary perspective. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia Riehemann, S. (2001), A Constructional Approach to Idioms and Word Formation, PhD thesis, Stanford University. Riehemann, S. (2001), A Constructional Approach to Idioms and Word Formation, PhD thesis, Stanford University. Sinclair, J. (1991) Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sinclair, J. (2008). The phrase, the whole phrase, and nothing but the phrase. Granger, S. & Meunier, F. Phraseology -An interdisciplinary perspective. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia. Smirnitsky A. I. (1959). Russian – English Dictionar. 3rd Edition edition . E. P. Dutton and Company. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia. (1979) file:///E:/Frazeologji%20dhe%20 Metafore/New%20Folder%20UNITE%20PHRASEOLOGIQUE /Phraseology.htm Thomai, J. (1981). Çështje të frazeologjisë së gjuhës shqipe. Tiranë. Thomai, J. (1999). Fjalor frazeologjik i gjuhës shqipe. Tiranë. Thomai, J. (2006). Leksikologjia e gjuhës shqipe. Botimet Toena, Tiranë. Vinogradov V. V. (1947). ‘Ob osnovnyx tipach frazeologiþeskix edijic v sovremennom russkom jazyke’. In: V. V. Vinogradov, Izbrannyje trudy: leksikologija i leksikografija. Moskva: Nauka. Wray, A. (2002). Formulaic Language and the Lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ȈȣȝİȦȞȓįȘȢ, ȋ. (1997). «Türkisch-griechische phraseologische Isoglossen anhand von Bezeichnungen für menschliche Körperteile und Organe». Zeitschrift für Balkanologie. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ̱͵Ͷ͵̱