A Carbon Tax in the Context of Tax Reform and... Budgetary, Economic, Distributional, and Emissions Impacts

advertisement

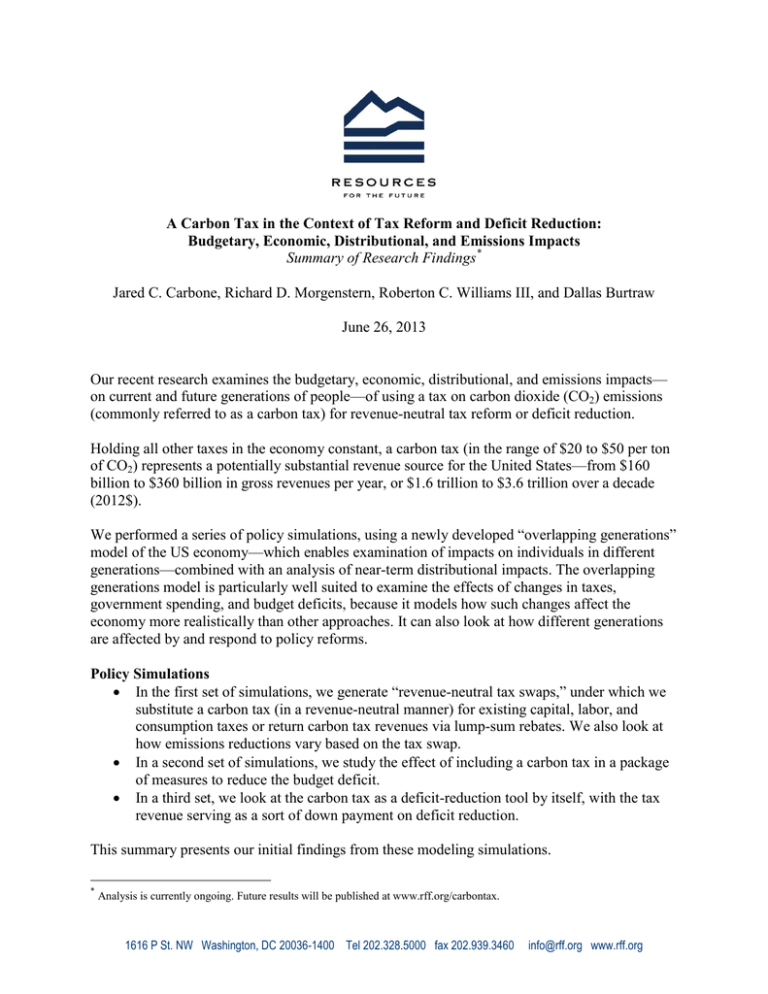

A Carbon Tax in the Context of Tax Reform and Deficit Reduction: Budgetary, Economic, Distributional, and Emissions Impacts Summary of Research Findings* Jared C. Carbone, Richard D. Morgenstern, Roberton C. Williams III, and Dallas Burtraw June 26, 2013 Our recent research examines the budgetary, economic, distributional, and emissions impacts— on current and future generations of people—of using a tax on carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (commonly referred to as a carbon tax) for revenue-neutral tax reform or deficit reduction. Holding all other taxes in the economy constant, a carbon tax (in the range of $20 to $50 per ton of CO2) represents a potentially substantial revenue source for the United States—from $160 billion to $360 billion in gross revenues per year, or $1.6 trillion to $3.6 trillion over a decade (2012$). We performed a series of policy simulations, using a newly developed “overlapping generations” model of the US economy—which enables examination of impacts on individuals in different generations—combined with an analysis of near-term distributional impacts. The overlapping generations model is particularly well suited to examine the effects of changes in taxes, government spending, and budget deficits, because it models how such changes affect the economy more realistically than other approaches. It can also look at how different generations are affected by and respond to policy reforms. Policy Simulations In the first set of simulations, we generate “revenue-neutral tax swaps,” under which we substitute a carbon tax (in a revenue-neutral manner) for existing capital, labor, and consumption taxes or return carbon tax revenues via lump-sum rebates. We also look at how emissions reductions vary based on the tax swap. In a second set of simulations, we study the effect of including a carbon tax in a package of measures to reduce the budget deficit. In a third set, we look at the carbon tax as a deficit-reduction tool by itself, with the tax revenue serving as a sort of down payment on deficit reduction. This summary presents our initial findings from these modeling simulations. * Analysis is currently ongoing. Future results will be published at www.rff.org/carbontax. 1616 P St. NW Washington, DC 20036-1400 Tel 202.328.5000 fax 202.939.3460 info@rff.org www.rff.org Using a Carbon Tax for Revenue-Neutral Tax Swaps Economic Impacts Using carbon tax revenues to cut other taxes in a revenue-neutral manner has a range of effects. Reducing capital taxes: Using carbon tax revenues to lower capital taxes (that is, corporate taxes or personal income rates on interest, dividends, or capital gains) produces the largest economic benefits, roughly offsetting the economic cost of a carbon tax. In this case, gross domestic product (GDP) rises slightly, while economic welfare—a more comprehensive measure of economic effects—declines slightly. Setting aside the environmental benefits from reduced CO2 emissions, the net costs of a carbon tax are close to zero. Reducing labor taxes: Recycling the revenues via reductions in labor taxes (in the form of either payroll tax cuts or personal income tax reductions) is less economically efficient than recycling the revenue through capital tax reductions, though the differences are relatively modest. Reducing consumption taxes: This is less economically efficient than either of the other tax-reduction options, though, again, the difference is relatively small. Providing lump-sum rebates: Recycling the revenues via lump-sum rebates to households is worse for the economy than any of the options that involve tax rate reductions. Impacts on Households Reducing capital taxes benefits high-income households the most. Using the revenue for a lump-sum rebate benefits low-income households the most. Reducing taxes on labor or consumption provides relatively equal benefits (as a percentage of income) to low- and high-income households. The effects on households vary less across regions of the United States than across income groups. However, some variations still exist. The regions of the country that benefit from tax swaps include the west, parts of the northeast, and the state of Florida. Regions that are adversely affected include the Plains states, the Deep South, Appalachia, and the Midwest. Impacts on Emissions Reductions The method of recycling carbon tax revenues has small but noticeable impacts on overall emissions reductions, primarily reflecting differences in economic growth among the cases. Reducing capital taxes: For any given carbon tax rate, the emissions reductions are smallest (that is, emissions levels are highest) when the carbon tax revenues are used to cut capital taxes. Reducing labor taxes or consumption taxes: Reducing taxes on labor yields larger emissions reductions than reducing capital taxes, and reducing consumption taxes results in even greater emissions reductions. Providing lump-sum rebates: Recycling carbon tax revenue via lump-sum rebates provides the largest emissions reductions. 2 Impacts on Different Generations Reducing capital taxes: Using carbon tax revenues to lower capital taxes yields net costs that are similar across generations. Reducing labor taxes: Using carbon tax revenues to fund reductions in labor taxes benefits younger generations at the cost of older generations. Providing lump-sum rebates or reducing consumption taxes: Using carbon tax revenues to fund lump-sum rebates or cuts in consumption taxes has the opposite effect—older generations benefit more than younger generations under this option. Impacts of a Revenue-Neutral $30 Carbon Tax on Different Generations, by Birth Year 100 $/year Net Present Value 50 0 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 -50 -100 -150 -200 Birth Year Carbon tax in lieu of a capital tax Carbon tax in lieu of a labor tax Carbon tax in lieu of consumption tax Carbon tax with lump sum rebate Note: This figure displays the intergenerational effects of the different revenue-recycling options in terms of economic welfare. For example, it shows the effect of a carbon tax–labor tax swap as -$50 for individuals born in 1985. This means that the net economic effect of that tax swap on the average person born in 1985 is the equivalent of losing $50 per year starting at the time the policy takes effect and continuing for the remainder of that individual’s life. 3 Using a Carbon Tax to Reduce the Deficit The Congressional Budget Office expects the federal deficit to begin rising again as a percent of GDP in 2016. Following Domenici–Rivlin Debt Reduction Task Force Plan (2012), we model policies where federal expenditures will be cut and federal revenues increased in equal amounts to address the deficit. Our simulations use revenues from carbon taxes to offset increases in capital, labor, and consumption taxes that would otherwise be necessary to address the deficit, while keeping expenditure reductions the same across all the tax options considered. The pattern of results among the deficit reduction options is very similar to revenue-neutral tax swap policies. Offsetting capital tax increases provides the most economic benefits, followed by offsetting labor and consumption taxes, and then the provision of lump-sum rebates. Using carbon tax revenues to offset increases in consumption tax increases benefits older generations at the cost of younger generations. Using the revenues to offset labor tax increases aids younger generations the most. Using carbon tax revenues to offset capital tax increases yields net costs that vary relatively little across generations. Deficit Reduction—Now Rather than Later A final set of simulations, also focusing on deficit reduction, uses a carbon tax as a down payment in advance of the larger spending reductions and tax increases required to bring the long-term deficit down to a sustainable level. In this set of simulations, a carbon tax makes it possible to start paying down the deficit sooner (and thus reduces the need for other tax increases in the future), whereas the previous set of simulations compared policy options with and without a carbon tax, but with the path of the deficit the same in both options. We find the following under this scenario: Early imposition of the carbon tax can generate substantial economic gains, even when environmental benefits are not considered. The intergenerational consequences may make this a politically difficult option, as every generation currently old enough to vote is worse off in this case, while today’s very young and future generations benefit greatly. 4