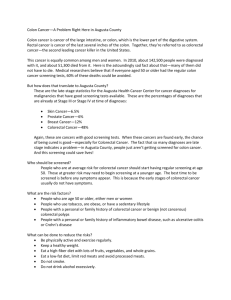

Colorectal Cancer What is colorectal cancer?

advertisement