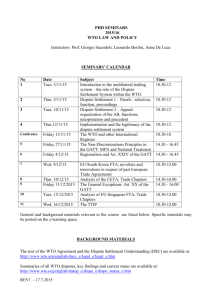

I P C

advertisement