Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease in Women AcademyHealth

advertisement

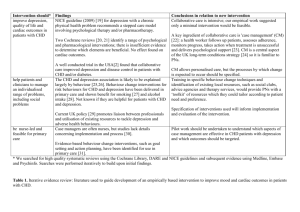

Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease in Women Chloe E. Bird Shih, RA, Eibner C, Griffin BA, Slaughter ME, Whitsel E, Margolis K, Escarce JJ, Jewell A, Mouton C, Lurie N AcademyHealth June 30, 2009 Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) Is a Leading Cause of Death in Women • Prognosis is markedly worse for women • Declines in CHD mortality are less pronounced for women • Established risk factors − − − − Low individual-level socioeconomic status (SES) Poor health behaviors Diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension Family history • Could the socioeconmic status of one’s neighborhood influence CHD risk? 2 6/29/2009 How Might Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status (NSES) Affect Risk of CHD? • Increased exposure to stressors such as violence and poverty • Reduced availability to outlets for nutritious food and physical activity • Reduced access to quality health care services • Increased exposure to environmental pollutants 3 6/29/2009 Study Objective To examine the relationship between NSES and incident CHD events and deaths in women in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) 4 6/29/2009 Data • • Geo-coded WHI Clinical Trial − N=68,132 women, age 50-79 − Followed for up to 12 years − Data from 76 U.S. sites − Physician-adjudicated CHD outcomes RAND Center for Population Health and Health Disparities Data Core − NSES data at the census tract level 5 6/29/2009 Components of NSES Index • Median household income • Adults ≤ high school education (%) • Male unemployment (%) • Households with income below poverty (%) • Households receiving public assistance (%) • Households headed by a single female (%) 6 6/29/2009 CHD Outcomes CHD event 6.9% (4,688) Myocardial Infarction (MI) or CHD death 3.2% (2,195) CHD death 0.9% (620) 7 6/29/2009 Methods • Cox Proportional Hazard models • Adjusted for baseline individual-level − Socio-demographic characteristics − Related comorbid conditions − Health behaviors − Family history of MI • Accounted for geographic clustering 8 6/29/2009 Baseline Characteristics • Race/ethnicity − 82% non-Hispanic white − 10% non-Hispanic black − 4% Hispanic • 61% Married • 94% ≥ High school • Household income − 42% ≤ $34,999 − 22% − 36% $35,000 - $74,999 ≥$75,000 9 6/29/2009 Lower NSES Is Independently Associated with Increased Hazard of CHD Event or Death Hazard Ratios 1.03 1.02 1.01 1.00 1.02 1.01 CHD event 1.01 MI/CHD death CHD death 10 6/29/2009 Results In a Real World Context Northwest DC Southeast DC 11 6/29/2009 CHD Hazard Ratios: Southeast vs. Northwest DC Hazard Ratios 2.00 1.80 1.60 1.50 1.40 1.23 1.27 1.20 1.00 CHD event MI/CHD death CHD death 0.80 12 6/29/2009 Limitations • Limited generalizability of the WHI sample • Longitudinal analysis not sufficient to infer causality • Healthier individuals may choose to live in better neighborhoods 13 6/29/2009 Conclusions • Living in a lower NSES neighborhood is associated with greater CHD risk among older women • Future research should examine mechanisms through which neighborhood characteristics influence health and risk of death • Social policies targeting neighborhood characteristics may improve both individual and population health 14 6/29/2009 Collaborators Christine Eibner, co-PI Nicole Lurie, CPHHD Center Director Jose Escarce Karen Margolis Meena Fernandes Regina Shih Bonnie Ghosh-Dastidar Mary Ellen Slaughter Beth Ann Griffin Eric Whitsel Adria Jewell Study funded by NHLBI R01HL084425 The authors declare no conflict of interest 15 6/29/2009 16 6/29/2009 Extra Slides 17 6/29/2009 Limitation: Selection of Women into Neighborhoods • Individuals may self-select into neighborhoods spurious correlation between neighborhood SES and health outcomes • Control for a comprehensive set of individual characteristics • Propensity score analysis − Weighted women with different levels of NSES to be well balanced on the covariates • Analysis of movers − Assume that CHD takes several years to develop − If a recent move appears to influence CHD mortality, then this is likely to be a selection effect 18 6/29/2009 Strengths • Examined CHD in women • Geographic and racial heterogeneity • Longitudinal data with up to 12 years of followup • Physician-adjudicated CHD outcomes • Robust index of NSES beyond area-level education and income 19 6/29/2009 Methods • Cox Proportional Hazard model analyze time until adverse CHD events • Shared frailty models account for geographic clustering of women at the census tract and Metropolitan statistical area levels hijk (t ) = ho (t )α j ρ k exp( xijk β ) • Neighborhood variables (x) measured at the census tract level, from RAND’s CPHHD Data Core 20 6/29/2009 Many Gaps in Existing Literature • Traditionally, CHD has been understudied in women relative to men • Current literature on neighborhood status and CHD suggests that neighborhood context may have a bigger effect on women than men • Prior studies on neighborhoods and health: − Had limited geographic and racial heterogeneity − Neglected the relative importance of residential instability − Were cross-sectional in nature − Lacked physician-adjudicated CHD outcomes − Lacked a robust NSES index beyond education income six neighborhood factors 21 6/29/2009 Limitations • Limited generalizability of the WHI CT sample • Individuals may self-select into neighborhoods spurious correlation between neighborhood SES and health outcomes • Inclusion of baseline comorbid conditions and health behaviors may be influenced by NSES • Longitudinal data not sufficient to infer causality 22 6/29/2009 Model Building • Model 1 adjusts for: − Individual-level sociodemographic controls • Race/ethnicity, education, income, martial status, region, study arm, and region of the U.S. − Neighborhood-level controls • Length of residency, percent owner occupied housing, and percent black or Hispanic • Model 2 additionally adjusts for: − Individual-level baseline health status • BMI, waist hip ratio, self-reported history of diabetes, hyperlipidemic medication use and/or self reported high cholesterol, hypertension, smoking pack-years, alcohol use, and hormone use 23 6/29/2009 *Sensitivity analyses allowing some covariates to be time-varying CPH Model Results CHD Death Model 1 Model 2 CHD Death or MI Model 1 Model 2 Any CHD Event Model 1 Model 2 Census-tract-level predictors NSES 0.984 0.990 0.986 0.990 0.989 0.993 (0.968, 1.000) (0.974, 1.006) (0.977, 0.995) (0.981, 0.999) (0.982, 0.995) (0.986, 0.999) Length of residency 0.687 0.571 1.014 0.919 1.029 0.969 (0.221, 2.138) (0.182, 1.789) (0.548, 1.874) (0.495, 1.707) (0.662, 1.599) (0.621, 1.513) % Owner Occupied Housing 0.909 0.918 0.931 0.907 0.975 0.928 (0.441, 1.872) (0.443, 1.902) (0.627, 1.384) (0.607, 1.354) (0.730, 1.302) (0.693, 1.244) Model 1: Individual-level socio-demographic + neighborhood-level variables Model 2: Model 1 + individual-level baseline health status 24 6/29/2009 Neighborhoods Influence CHD Directly, and Indirectly Through Mediators Neighborhood Built Environments Baseline Health Status Demographics Individual Characteristics Neighborhood Social Environments Per Capita County Medical Care Resources Community Characteristics Social Support Health Habits Follow-Up Health Status Incident CHD Outcomes Psychological Well-Being Mediating Factors CHD Outcomes 25 6/29/2009 WHI Data Data Category Examples Individual Demographics Age, race, education, income Social Support Social activities, emotional and instrumental support Quality of Life Depression, personal outlook, life satisfaction Behavioral Risk Factors Smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, diet Health Status Family health history, biomarkers, chronic illness Medical Care Medications, use of medical care CHD & Mortality Outcomes MI, angina, revascularization 26 6/29/2009 Longitudinal Aspect of WHI Has the Potential to Enhance Knowledge of Neighborhoods and Health • Majority of studies on neighborhoods and health are cross sectional • Entwisle (2007) found that—of 503 studies on neighborhoods and health—only 2.4 percent used longitudinal data − Concluded that lack of longitudinal studies is a limitation of the current literature • Longitudinal data can be used to explore lagstructure of relationship between neighborhoods and health 27 6/29/2009 Other Considerations In additional models, we also examine: • % of census tract residents who are Hispanic • % of census tract residents who are Black • Whether participants live in, or near a metropolitan area − Two sets of analyses; one set limited to the MSA residents, second set using measures of health care supply for nonmetropolitan areas • Physician supply at the MSA or county level • Relative contribution of residential stability • Effect modification of NSES effects by residential stability 29 6/29/2009 Lower NSES Is Associated with Increased Risk CHD death CHD death/MI Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2 0.984 0.990 0.977 0.990 CHD event Model 1 Model 2 0.989 0.993 1.10 1.00 0.90 0.80 0.70 0.60 Model 1 Adjusts for individual-level socio-demographic + neighborhood-level variables Model 2 Adjusts for Model 1 covariates + individual-level baseline health status 30 6/29/2009 Two Washington, D.C. Areas Illustrate Neighborhood Effects on CHD Risk CHD death 0.584 CHD death/MI 0.724 CHD event 0.753 1.10 1.00 0.90 0.80 0.70 0.60 0.50 0.40 • Compared to the same woman living in Northwest D.C. (top 25%), one living in Southeast D.C. (bottom 25%) has - 71% higher risk of CHD death (95% CI = 31%,123%) - 38% higher risks of CHD death or MI (95% CI = 19%,61%) - 32% higher risk of any CHD event (95% CI = 20%, 48%) 31 6/29/2009 Residential stability • Residential instability may influence health through: − Limited access to health care − Reduced social support • High stability in low SES neighborhoods may reflect blocked opportunities that affect health Kirby & Kaneda, 2006; Rozanski et al., 1999; Chaix et al., 2006; 2007 32 6/29/2009 Results In a Real World Context Northwest DC Southeast DC 33 6/29/2009