Moderators of Treatment Effects in the General Medicine Literature:

advertisement

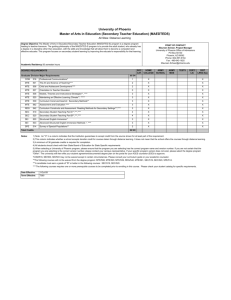

Moderators of Treatment Effects in the General Medicine Literature: Looking for Improvement Nicole Bloser, MHA, MPH University of California, Davis June 5, 2007 1 Background Parallel group randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the cornerstone of evidence based medicine Result: Average of usually immeasurable individual effects Some benefit, some harmed Heterogeneity of treatment effects 2 Background Examining treatment impact in similar individuals or subgroups N-of-1 clinical trial Prospective stratification with a multivariable risk index Subgroup analysis 3 Background Subgroup analysis – problems Low power Multiple testing Not all subgroup analysis is the same P-value within subgroup ≠ interaction analysis Interaction analysis is the correct way to examine moderators of treatment effects (MTEs) 4 Background MTEs necessary to maximize benefit and minimize harm MTEs often not examined (<50% of RCTs report interaction analysis) Studies that examine MTE reporting: Majority in cardiovascular literature None since revised CONSORT statement (2001) 5 Research Objective We sought to identify current practice in evaluating moderators of treatment effects (MTEs) and to elucidate trends Persistent low rate of analyses would suggest Missed opportunities Slower progress towards personalized medicine 6 Study Design Systematic review Annals, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet, NEJM Odd months, 1994, 1999, 2004 Randomized controlled trials Unit of randomization as the individual All independently reviewed and coded by two investigators Adjudication by a third 7 Study Selection 4863 articles from initial search Exclude: All articles that were not clinical trials. N=4,322 N=541, Random sample of N=379 selected Include Exclude N=303 articles 319 trials included N=76 articles 9 trials excluded 77 trials excluded Reasons for exclusion: Not RCT (N=61 trials) Unit of randomization not individual patient 8 (N=25 trials) Methods Trials were coded as having MTE analysis (utilizing a formal test for heterogeneity) Subgroup analysis only (no formal test) Neither Chi-square test used for bivariate comparisons Multiple logistic regression used to identify predictors of MTE analysis 9 Trial Characteristics n (%) Journal of Publication Annals BMJ JAMA Lancet NEJM Year of Publication 1994 1999 2004 Condition Studied Cardiovascular Cancer Infectious Disease Psych / Neuro Other 30 (9) 47 (15) 50 (16) 101 (32) 91 (29) 91 (29) 106 (33) 122 (38) 74 (23) 42 (13) 70 (22) 25 (8) 108 (34) 10 Trial Characteristics 38% of trials had authors from North America (US and Canada) 95% utilized a parallel group design Study sample size ranged from 6-41,000 (Median: 262, IQR: 101-708) 11 MTE and Subgroup Reporting Analysis reported None Subgroup without statistical comparison MTE n (%) 139 (45) 88 (28) 92 (29) For those trials reporting MTE analysis: 43 (47%) reported on one covariate 24 (26%) reported on 2-4 covariates 17 (18%) reported on 5-10 covariates 7 (7%) reported on 11-19 covariates 12 Covariates examined for MTE Among those trials that reported MTE, major covariates examined included: Individual Risk Factors Gender Age Study Site Co-occurring treatment Co-morbidities Race/Ethnicity % 56% 36% 29% 29% 25% 21% 15% Only one trial reported MTE analysis using a composite multivariable risk index. 13 Bivariate analysis Journals published in North America (Annals, JAMA) and first authors writing from North America were more likely to publish trials with MTE analysis Sample size (p<0.0001 for trend) Quintile 1: 14%, Quintile 5: 52% More MTE analysis reported in each of the three successive time periods (p=0.047) 14 Logistic Regression Prediction of MTE analysis Included in model: study year, journal clinical condition, first author’s region, and sample size Journal and sample size were significant Reference categories: BMJ, Quintile 1 JAMA: 4.4 (1.4, 13.5), Annals: 4.2 (1.2, 15.1) Quintile 5: 7.5 (2.9, 19.3) 15 Limitations Limited number of trials reviewed MTE results are published elsewhere MTE examined, but not reported due to nonsignificance 16 Conclusions Missed opportunities for MTE analysis abound Conservative reaction that stifles hypothesis generation Impairs recognition of patient strata Impedes future research When subgroups are reported, the reporting is not done correctly in many (~50%) cases. This could lead to erroneous conclusions. 17 Conclusions NIH guidelines regarding subgroup specific results recommends reporting both significant and non-significant results, yet only half of the trials reported any MTE analysis. In the face of broad NIH mandates for inclusion of subjects by race/ethnicity, the low proportion of trials examining race/ethnicity as a treatment effect modifier is puzzling. 18 Policy Implications MTE analysis critical to future research The genomic revolution is only going to increase the desire to individualize treatment effects Kraemer et al. argue that exploratory moderator analysis is critical for designing future confirmatory studies Significant exploratory effects are later used as guidance for future stratification Kraemer, HC, E Frank, and DJ Kupfer, Moderators of treatment outcomes: clinical, research, and policy importance. Jama, 2006. 296(10): p. 1286-9. 19 Policy Implications Rigorous and routine exploratory MTE analysis is necessary and should be encouraged Standards are essential for developing practice guidelines that are appropriate to the needs of complex patients 20 Research Team University of California, Davis University of California, Los Angeles Richard Kravitz, MD, MSPH - PI Elizabeth Yakes, MS Naihua Duan, PhD - PI Diana Liao, MPH Kiavash Nikkhou 21 Thank you 22