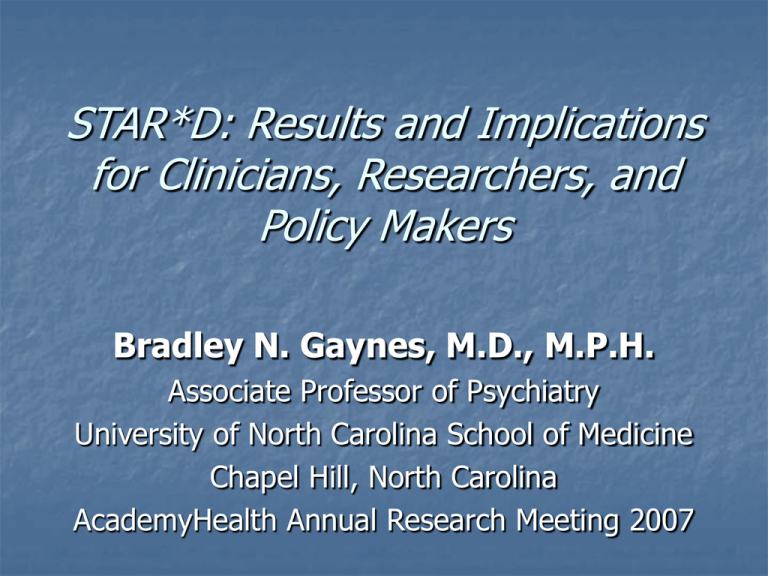

STAR*D: Results and Implications for Clinicians, Researchers, and Policy Makers

advertisement

STAR*D: Results and Implications for Clinicians, Researchers, and Policy Makers Bradley N. Gaynes, M.D., M.P.H. Associate Professor of Psychiatry University of North Carolina School of Medicine Chapel Hill, North Carolina AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting 2007 What is STAR*D? Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression www.star-d.org Overall Aim of STAR*D Define preferred treatments for treatment-resistant depression Overview - I Duration: 7 years (October 1999 September 2006) Funding: National Institute of Mental Health National Coordinating Center, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas Data Coordinating Center, Pittsburgh 4 Overview - II 14 Regional Centers 41 Clinical Sites 18 Primary Care Settings (PC) 23 Psychiatric Care Settings (Specialty Care, or SC) Level 1 Obtain Consent Satisfactory response CIT Follow-Up Unsatisfactory response* Level 2 *Response = >50% improvement in QIDS-SR from baseline Level 2 Randomize SER BUP-SR VEN-XR Switch Options CT CIT + CIT + CIT + BUP-SR BUS CT Augmentation Options Level 2A Randomize BUP-SR VEN-XR Switch Options Level 3 Randomize MRT NTP Switch Options L-2 Tx + Li L-2 Tx + THY Augmentation Options Level 4 Randomize TCP VEN-XR + MRT Switch Options Participants Major depressive disorder Nonpsychotic Representative primary and specialty care practices (nonacademic/non efficacy venues) Self-declared patients Inclusion Criteria Clinician deems antidepressant medication indicated. 18-75 years of age. Baseline HRSD17 14. Most concurrent Axis I, II, III disorders allowed. Suicidal patients allowed Clinical Procedures Open treatment with randomization Symptoms/side effects measured at each clinical visit (measurementbased care, or MBC) Clinicians guided by algorithms/ supervision Research Innovations “Real world” patient participants from nonacademic/nonefficacy research venues Non-research clinicians Identical criteria and concurrent enrollment from PC and SC sites Broadly selective inclusion criteria Patient preference built into study design STAR*D Hybrid Design - I Patients Masked Treatment Masked Raters Baseline Severity Diagnostic Method Concurrent Axis I and Axis III Allowed Efficacy* Effectiveness STARD Symptomatic Volunteers Yes Self-declared Self-declared No No Yes Yes Yes HRSD17 >20 Variable HRSD17 >14 Structured Interview Minimal Clinical Clinical Most† Most† *To establish efficacy versus placebo. †Allowed to enter if MDD requires medication. STAR*D Hybrid Design - II Efficacy* Effectiveness Treatment Methods STARD Protocol Clinician Yes Sometimes Protocol + Clinician Yes No No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Sometimes‡ Placebo Allowed Yes No No Suicidal Patients Allowed No Yes Yes Symptomatic Outcomes Functional Outcomes Cost/Utilization Outcomes Psychotherapy Allowed *To establish efficacy versus placebo. ‡Allowed if not depression-targeted, empirically tested therapy. Level 1 Findings Patients from real world settings are quite chronically ill Mean (SD) HRSD17 (ROA) 21.8 (5.2) No. of MDEs 6.0 (11.4) Length of current MDE (months) 24.6 (51.7) Length of illness (years) 15.5 (13.2) No. with either chronic or recurrent MDE Depressed ≥ 2 years No. with concurrent medical conditions 85% 25% 67% Depressed patients in PC and SC settings are surprisingly similar No difference in depressive severity distribution of depressive severity specific depressive symptom presentation likelihood of presenting with a comorbid psychiatric illness Main difference: SC patients more likely to have made prior suicide attempt, but common in both (20% vs. 14%, p<0.0001) Outcomes for PC and SC depressed patients were identical Remission rates were the same (27% PC vs. 28% SC, p=0.40) Time to remission did not differ by site (6.7 weeks PC vs. 7.3 weeks CS, p=0.11) Gaynes et al., BMJ, under review Time to Remission (QIDS-SR 16) by Clinical Setting Log-Rank Test=2.6: p=0.1063 Weeks in Level 1 No. of patients Primary 1004 Specialty 1643 Total 2647 879 1519 2398 709 1254 1964 520 975 1495 342 633 975 175 294 469 21 28 49 Gaynes et al., BMJ, under review Conclusions One-quarter of patients have been depressed for >2 years and 2/3 have concurrent GMCs About 1/3 will remit Response occurs in 1/3 AFTER 6 weeks MBC is feasible and works, with equivalent outcomes in PC or SC settings Studies of remission require longer study periods than 8 weeks Level 2 Medication Switch Conclusions: Level 2 Switch Either switching to the same class of antidepressant (SSRI to SSRI) or to a different class (SSRI to non-SSRI) did not matter Substantial differences in pharmacology did not translate into substantial clinical differences in efficacy Level 2 Medication Augmentation Conclusions: Level 2 Augmentation There was no substantial differences in the likelihood of either of the two augmentation medications to produce remission Patients had clear preferences about accepting augmentation vs. switching, and, accordingly, the groups differed at entry into level 2 Consequently, whether switching vs. augmenting is preferred after one treatment failure could not be addressed QIDS-SR16 Remission Rates 80 * 60 Percent 40 53.0% 32.9% 30.6% 20 0 L-1 * Theoretical L-2 Overall Conclusions Cumulative remission rate is over 50% with first 2 steps Patient preference plays a big role in strategy selection Pharmacological distinctions do not translate into large clinical differences Level 2 Cognitive Therapy Findings Conclusions CT is an acceptable switch option in the second step CT is an acceptable augmentation option in the second step Whether CT responders/remitters fare better in follow-up is in analysis CT was not as popular as expected Remission Rates by Levelsa a Level 1 (2876) 32.9 Level 2 (1439) Switch (789) Augment (650) 30.6 27.0 35.0 Level 3 (377) Switch (235) Augment (142) 13.6 10.3 19.1 Level 4 (109) 14.7 By QIDS-SR16 <5 at level exit Are Efficacy and Real World Patients Different? STAR*D Participant Flow (CONSORT Chart) Screened (4,790) Ineligible (136) Consented (4,177) Eligible (4,041) Failed to Return (234) HRSD17 >14 (3,110) Not offered Consent or Refused to Consent (613) HRSD17 < 14a (607) Or Missing (324) Eligible for Analysis (2,876) Efficacy Sample (635) Nonefficacy Sample (2,220) Some of these subjects were eligible for entry into Level 2. Wisniewski et al, The Lancet, in preparation a Could Not Be Classified (21) Clinical Featuresa Feature Illness duration (yrs.)b Suicide attemptc Anxious featuresb Atypical featuresb Melancholic features Psychiatric careb Efficacy (n=635) 13 15% 47% 14% 25% 70% Nonefficacy (n=2220) 16 19% 55% 20% 23% 59% Descriptive statistics presented as mean±sd and n (%N). Sums do not always equal N due to missing values. Percentages based on available data; b p<.01; c p<.05 a Wisniewski et al, The Lancet, in preparation Outcomesa - I Outcome QIDS-SR16 remission Efficacy (n=635) 35% Nonefficacy (n=2220) 25% QIDS-SR16 response 52% 39% Exit QIDS-SR16 8.6+5.2 QIDS-SR16 % change -45.4+33.2 10.0+5.6 -37.4+33.3 Descriptive statistics presented as mean±sd and n (%N). Sums do not always equal N due to missing values. Percentages based on available data a QIDS-SR16 = 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self-report Wisniewski et al, The Lancet, in preparation Outcomesa - II Adjusted Analysesb Outcome QIDS-SR16 remission OR 1.331 (95% CI) (1.073,1.651) P 0.0093 QIDS-SR16 response 1.371 (1.122,1.675) 0.0020 Β (95% CI) P Exit QIDS-SR16 -0.681 (-1.198,-.165) 0.0098 QIDS-SR16 % change -4.276 (-7.424,-.129) 0.0078 Outcome Descriptive statistics presented as mean±sd and n (%N). Sums do not always equal N due to missing values. Percentages based on available data; b Adjusted for regional center, clinical setting, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, employment status, income, medical insurance, marital status, illness duration, suicide attempt, family history of substance abuse, anxious and atypical features; QIDS-SR16 = 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self-report Wisniewski et al, The Lancet, in preparation a Phase III clinical trial criteria do not recruit samples representative of depressed patients who seek treatment in typical clinical practice. The use of broader inclusion criteria would make findings more generalizable to typical care-seeking outpatients may reduce placebo response and remission rates in Phase III trials, and may reduce the risk of failed trials, at the risk of increasing adverse events and decreasing symptomatic benefit. What is the pay off? By any measure, success Over 4000 patients involved Over 150 clinicians Active involvement of PC sites 51 publications to date, and more in press or preparation At least 3 large scale ancillary studies (Child, Alcohol, Genetics), each of which has its own cadre of publications Depression Treatment Network infrastructure, supporting rapid trial turn around What questions could not be answered? How does high quality measurementbased care compare to usual care? Is switching or augmentation the preferred strategy after 1 or 2 failures? What is the role of cognitive therapy? What important questions does STAR*D raise? Clinical Given chronicity and low remission rates of most depressions, should combination meds (“broad spectrum antidepressants”) be started at initial treatment step? How do you balance the effort at adequately treating those identified with identifying those undetected? Could system keep up? Study Design How best do you handle the role of patient preference in study design? Policy Why not include more broadly representative patients in placebo-controlled trials used to develop treatments? If you could ensure patient safety and ensure internal validity in such trials, the results would be more directly applicable to our patients, who are less likely to spontaneously improve. What should the arsenal of available antidepressants be at the state level? How best do you keep these infrastructures funded? The STAR*D Study Investigators National Coordinating Center A. John Rush, MD Madhukar H. Trivedi, MD Diane Warden, PhD, MBA Melanie M. Biggs, PhD Kathy Shores-Wilson, PhD Diane Stegman, RNC Michael Kashner, PhD, JD Data Coordinating Center Stephen R. Wisniewski, PhD G.K. Balasubramani, PhD James F. Luther, MA Heather Eng, BA. University of Alabama Lori Davis, MD University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Leuchter, MD Ira Lesser, MD Ian Cook, MD Daniel Castro, MD University of California, San Diego Sidney Zisook, MD Ari Albala, MD Timothy Dresselhous, MD Steven Shuchter, MD Terry Schwartz, MD Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago William T. McKinney, MD William S. Gilmer, MD The STAR*D Study Investigators University of Kansas, Wichita and Clinical Research Institute Sheldon H. Preskorn, MD Ahsan Khan, MD Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston Jonathan Alpert, MD Maurizio Fava, MD Andrew A. Nierenberg, MD University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Elizabeth Young, MD Michael Klinkman, MD Sheila Marcus, MD New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York Frederic M. Quitkin, MD Patrick J. McGrath, MD Jonathan W. Stewart, MD Harold Sackeim, PhD University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Robert N. Golden, MD Bradley N. Gaynes, MD The STAR*D Study Investigators Laureate Healthcare System, Tulsa Jeffrey Mitchell, MD William Yates, MD University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh Michael E. Thase, MD Edward S. Friedman, MD Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville Steven Hollon, PhD Richard Shelton, MD The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas Mustafa M. Husain, MD Michael Downing, MD Diane Stegman, RNC Laurie MacLeod, RN Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond Susan G. Kornstein, MD Robert K. Schneider, MD Pharmaceutical Industry Support for STAR*D Medications were provided gratis by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, King Pharmaceuticals, Organon Inc., Pfizer Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories.