Do Large Gaps in Prescription Coverage Matter Beyond the Generosity of Coverage?

advertisement

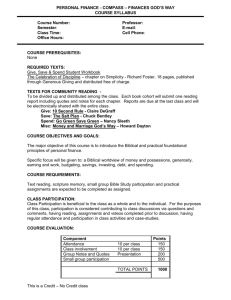

Do Large Gaps in Prescription Coverage Matter Beyond the Obvious Fact that they Reduce Generosity of Coverage? Bruce Stuart,* Joseph Terza,** Lirong Zhao* AcademyHealth annual meetings, Orlando 6/4/07 *University of Maryland Baltimore, **University of Florida University of Maryland Baltimore School of Pharmacy 1 Acknowledgement The Authors wish to thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for research support 2 Background The “doughnut hole” in the standard Medicare Part D benefit design is controversial for 3 reasons • • • It reduces the average value of the policy for medium-high spenders It impacts beneficiaries differentially The large gap may have pernicious effects in disrupting medication regimens 3 Background Large literature supports assertion that less generous drug coverage reduces demand Small literature on coverage gap effects Studies by Stuart et al. (2005), Simoni-Wastila et al. (2007) Studies of M+C benefit caps No study (that we are aware of) that examines independent effect of gaps controlling for generosity 4 Research questions Do Medicare beneficiaries who experience benefit gaps in prescription coverage spend less on medications than those with continuous coverage holding generosity constant? Does the relationship vary with gap duration? Does relationship vary at different levels of drug spending? 5 Research strategy Construct a test that captures essential elements of Medicare beneficiaries’ exposure to standard Part D design in 2006 Restrict to community-dwelling beneficiaries with some Medicare supplementation who spent >$250 per year on drugs measured in 2006 dollars No Medicaid recipients No gaps longer than 5.3 months per year Annual average generosity of benefits (% spending paid by 3rd party) >30% 6 Data Medicare Current Beneficiary Surveys from 1997 – 2003 Desirable qualities of MCBS Can identify beneficiaries with gaps in prescription coverage and gap duration Can also identify gaps and gap duration in Medicare supplemental insurance Can compute average generosity of drug coverage Less desirable qualities No plan design information 7 Study samples Base sample: N=27,802 person-years meet study inclusion/exclusion criteria Subsamples (non-exclusive) Employer sponsored Rx coverage (n=17,697) Medicare HMO Rx coverage (n=6,231) Self-purchased Rx coverage (n=5,682) 8 Measures Dependent variable: annual drug spending converted to 2006 constant dollars Independent variables Generosity (% spending paid by 3rd party) Rx coverage gap (0/1) Continuity of Rx coverage (% year with coverage) Continuity of Medicare supplement (% year with coverage) Covariates: age, sex, race, income, education, residence, health status, health care contacts, HCC risk adjuster, death, year dummies 9 Statistical analysis Regression models predicting drug spending for base sample and subsamples All person-years Person years with spending $250-$2,250 Person years with spending >$2,250 Model specification (GLM with Gamma and log link using robust command in Stata) Models with Rx gap (0/1) variable to test disruption hypothesis Models with continuity-of-Rx-coverage variable to test duration of gap hypothesis 10 Statistical issues Ex-post measure of generosity is endogenous Gap variables may or may not be endogenous depending on (unobserved) causal factors generating gaps Prior research indicates that HCC risk adjuster controls for Rx plan selection in studies using MCBS data Stuart et al., 2005, Stuart et al., 2006, Stuart et al, 2007 11 Sample characteristics Continuous coverage Coverage gaps % of sample Mean generosity % of sample Mean generosity Base Sample 90% 73% 10% 65% ESI 92% 76% 8% 70% MHMO 90% 68% 10% 61% Selfpurchased 85% 67% 15% 60% Sample 12 Mean annual Rx spending (sd) in 2006 constant dollars Continuous coverage Coverage gaps % of sample Mean Rx spend % of sample Mean Rx spend Base Sample 90% $2,155 ( 2,309) 10% $1,817 ( 2,053) ESI 92% $2,332 ( 2,474) 8% $1,904 ( 2,357) MHMO 90% $1,610 (2,051 ) 10% $1,362 ( 1,359) Selfpurchased 85% $2,025 ( 2,132) 15% $1,765 (1,537 ) Sample 13 Marginal effects (elasticities) of generosity in models with dichotomous Rx gap variable Sample Spending $250 - $2,250 Spending > $2,250 Base Sample 5.3*** (0.34) 30.4*** (0.56) ESI 7.1*** (0.46) 31.7*** (0.59) MHMO 5.2*** (0.34) 29.9*** (0.57) Self-purchased 2.8*** (0.16) 25.3*** (0.43) statistical significance ***p<.01, **p<,05, *p<.10 14 Marginal effects for dichotomous Rx coverage gaps variable Spending $250 - $2,250 Spending > $2,250 Base Sample -30.6** 1.4 (ns) ESI -67.1*** 10.0 (ns) MHMO 12.2 (ns) -267.3 (ns) Self-purchased -23.0(ns) -156.8 (ns) Sample statistical significance ***p<.01, **p<,05, *p<.10 15 Marginal effects (elasticities) for continuity of prescription coverage variable Spending $250 - $2,250 Spending > $2,250 Base Sample 1.1*** (0.10) -3.1 (ns) ESI 1.9*** (0.16) -4.6 (ns) MHMO 0.4 (ns) 5.4 (ns) Self-purchased 0.8 (ns) 1.1 (ns) Sample statistical significance ***p<.01, **p<,05, *p<.10 16 Discussion Study confirms previous research showing that generosity of coverage is a significant driver of drug spending Mixed support for idea that Rx coverage gaps have independent impact on drug spending Small gap effects found in base sample and ESI sample for those with spending between $250 and $2,250 No evidence that Rx coverage gap reduces spending among those spending >$2,250 17 Study limitations Ex-post measure of generosity is clearly endogenous but difficult to instrument (direction of potential bias also unclear) Endogeneity in gap variables is likely to bias results to the null (assuming that beneficiaries who chose—or fail to avoid— gaps have less need for medications) Control for gaps in underlying Medicare supplementation reduces likelihood of bias 18 Conclusions Findings are suggestive but not definitive regarding impact of the Part D doughnut hole on beneficiary spending over the year They do suggest that the debate over the doughnut hole should distinguish generosity-reducing effects from gapspecific dislocations in medication regimens 19