Importance

advertisement

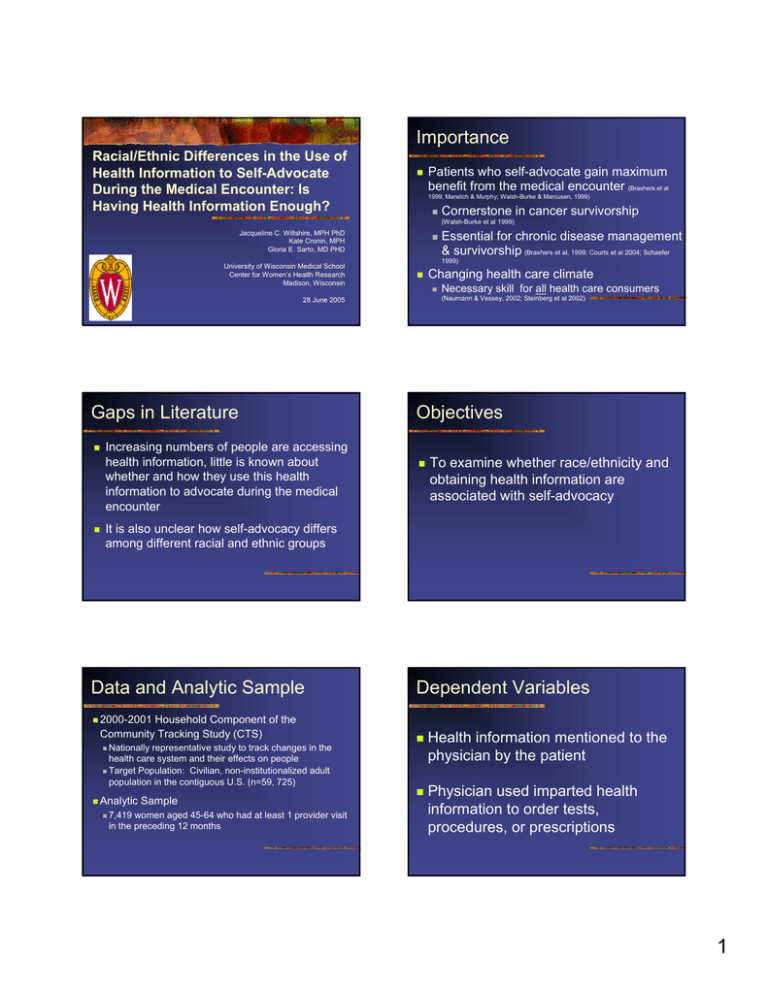

Importance Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Use of Health Information to Self-Advocate During the Medical Encounter: Is Having Health Information Enough? Patients who self-advocate gain maximum benefit from the medical encounter (Brashers et al 1999; Marelich & Murphy; Walsh-Burke & Marcusen, 1999) Cornerstone in cancer survivorship (Walsh-Burke et al 1999) Jacqueline C. Wiltshire, MPH PhD Kate Cronin, MPH Gloria E. Sarto, MD PHD University of Wisconsin Medical School Center for Women’s Health Research Madison, Wisconsin 1999) Increasing numbers of people are accessing health information, little is known about whether and how they use this health information to advocate during the medical encounter Changing health care climate Necessary skill for all health care consumers (Naumann & Vessey, 2002; Steinberg et al 2002) 28 June 2005 Gaps in Literature Essential for chronic disease management & survivorship (Brashers et al, 1999; Courts et al 2004; Schaefer Objectives To examine whether race/ethnicity and obtaining health information are associated with self-advocacy It is also unclear how self-advocacy differs among different racial and ethnic groups Data and Analytic Sample Household Component of the Community Tracking Study (CTS) Dependent Variables 2000-2001 Nationally representative study to track changes in the health care system and their effects on people Target Population: Civilian, non-institutionalized adult population in the contiguous U.S. (n=59, 725) Analytic 7,419 Sample women aged 45-64 who had at least 1 provider visit in the preceding 12 months Health information mentioned to the physician by the patient Physician used imparted health information to order tests, procedures, or prescriptions 1 Main Explanatory Variables Health Information 1. Internet 2. Friends 3. TV or Radio 4. Books/magazine/other source 5. Health care professional/health care organization Race/Ethnicity 1. White 2. African American (AA) 3. Hispanic Control Variables Age Marital status Rural living Education Employment Federal Poverty Level Insurance Usual source of care Perceived Health Status HMO Enrollment Frequency of sources 1, 2, 3+ sources Analysis Selected Characteristics of Respondents 70 Descriptives (frequencies) Binomial logistic regression (SUDAAN) 62.8 60 50 40 Account for complex survey design “SUBPOPN” statement in SUDAAN was used to select analytic sample Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals 30 20.6 20.9 20 11.8 10 0 Age (years) Selected Characteristics of Respondents 59.8 53.5 Married (%) Rural living (%) < High School (%) Main Explanatory Variables Weighted % of Health Information/Sources Weighted % of Race/Ethnicity 100 95.5 60 90 80 48.7 78 60 20 White African American Hispanic 70 39.4 20.8 1 Source 2 Sources 3+ Sources 50 80 40 Employed Poor/near(%) poor (%) 39.0 40 31.8 60 29.1 % 30 50 % 7.3 40 20 30 0 Usual Source of Care (%) Poor/Fair Health (%) Uninsured (%) HMO (%) 20 12 8 10 10 0 0 Race/Ethnicity All Info Combined Frequency of Sources 2 Among those who sought health information, frequency of sources, and self-advocacy by race/ethnicity Dependent Variables *Multivariate-adjusted % Mentioned Info to Physician Physician Ordered Tests 35 28.2% 30 25 20 17.3% 13.4% 15 10 8.3% Of the 28% who mentioned information to the physician n=1079), 48.7% perceived that they got tests ordered 5 0 Overall Sample (n=7419) Sample with Health Info (n=3960) a Model 1 (N=7419) 95% CI p-value q-value Sociodemographics Race/Ethnicity African American 0.52 (0.37-0.73) <0.001 0.001 Hispanic 0.79 (0.57-1.09) 0.156 0.223 White (reference) Sought Health Information Yes 4.76 (4.05-5.60) <0.001 0.001 No (reference) Frequency of health sources 3 2 1 (reference) Interactions Race x Poverty Level African American - Poor African American - Near-poor Hispanic - Poor Hispanic - Near-poor b OR Model 2 (N=3690) 95% CI p-value q-value c OR Model 3 (N=3690) 95% CI p-value q-value 0.57 (0.40-0.83) 0.004 0.013 0.92 (0.64-1.32) 0.647 0.715 0.68 (0.48-0.94) 0.022 0.072 0.92 (0.63-1.33) 0.653 0.742 2.24 (1.86-2.69) <0.001 0.001 1.41 (1.15-1.73) 0.001 0.004 2.24 (1.86-2.70) <0.001 0.001 1.40 (1.14-1.71) 0.001 0.005 0.72 0.39 1.35 0.59 (0.26-2.00) (0.16-0.96) (0.44-4.16) (0.23-1.52) 0.534 0.041 0.600 0.275 0.668 0.094 0.714 0.382 Summary Midlife women with health information are more likely to self-advocate than those without health information Self-advocacy differs by race/ethnicity White (n=3113) AA (n=342) Hispanic (n=215) 45.8 49.2 29.3 68.9 31.0b 44.6 34.0 75.0b 35.0c 45.2 38.5 70.2 5.1 50.0 4.5 40.4b 7.7 47.2 38.3 32.1 29.6 43.8 30.0 26.0 41.9 30.6 27.4 29.3 46.7 19.2b 49.2 27.0 64.3 *Adjusted for age, marital status, rural living, education, employment status, poverty level, usual source of care, health insurance, HMO status, and health status. Binomial Logistic Regression Models of Mentioned Health Information to Doctor OR Characteristic Sources of Health Info Internet Friends TV or Radio Books/magazine/other source Health care profs & orgs All Health Info Combined Frequency of Health Info 1 2 3 Self-Advocacy Mentioned Info to Physician Physician Ordered Tests African Americans less likely to obtain health information & less likely to advocate during the medical encounter Binomial Logistic Regression Model of Doctor Used Health Information to Order Tests a b Model 1 (N=1079) OR 95% CI p-valueq-value Sociodemographics Race/Ethnicity African American Hispanic White (reference) Freqency of Health Information 3 2 1 (reference) 1.11 (0.62-1.97) 0.721 0.831 2.15 (1.10-4.20) 0.025 0.131 0.75 (0.53-1.05) 0.095 0.307 0.69 (0.49-0.95) 0.024 0.131 Limitations Cross-sectional design limits causal conclusions Relatively high socioeconomic status Self-reported data – recall bias Cannot distinguish primary source of health information Omitted variables that may confound or mediate the observed relationships Patients attitudes (assertiveness, role perceptions) Situational factors (chronic conditions, type of illness, length of time with physician) 3 Conclusions While obtaining health information is associated with self-advocacy, this may not be enough among minority women, especially African Americans Thank You Lyn Bromley Center for the Study of Cultural Diversity in Health Care (UW Medical School) Future research needed to examine Factors that impede the ability of African American women to self-advocate Impact on unequal treatment 4