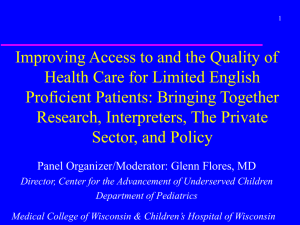

Language Barriers and Medical Interpretation

advertisement

Language Barriers and

Medical Interpretation

Academy Health

June 27, 2005, Boston, MA

“National Standards For Culturally & Linguistically

Appropriate Behavioral Health Care: Are We Kidding

Ourselves”

Eric J. Hardt MD

Clinical Director, Geriatrics Section, Boston Medical Center

Medical Consultant to Interpreter Services

Linguistic Minorities in the USA

Definition of NES, LEP

NES

LEP

USA

1990

13.8 %

6.0 %

USA

2000

17.9 %

8.1 %

MA

2000

18.7 %

8.1 %

Boston 2000

33.4 %

16.3 %

NYC

2000

47.6 %

23.7 %

LA

2000

57.8 %

32.6 %

Language and Access Mandates

4. Offer and provide language timely

assistance services without charge

5. Inform patients of their right to

receive language assistance services

6. Interpreters and bilingual staff

7. Patient-related materials and signage

Interactions between Culture and

Language

• Scenarios that include language

barriers are very likely to present

“cross-cultural” issues:

– Bias/discrimination/stereotypes/racism

[both personally-mediated and institutionalized]

– Culturally-mediated diversity in health-related

behaviors/values/preferences

– Power differentials

E Hardt 2005

Roles for Medical Interpreters

in Relation to “Cultural” Issues

• Interpreter is the conduit via which the

culturally competent provider may explore

differences in health related beliefs and

behaviors

• Interpreter adopts an expanded role that

includes explanation of features of medical and

of patient culture and brokerage of

relationships between patient and provider

• IN EITHER CASE THE PRIMARY

RESPONSIBILITY OF THE INTERPERTER IS

TO FAITHFUL TRANSMISSION OF

MESSAGES

E Hardt 2005

Clinical Issues I

• Outreach and marketing, signage,

telephone access

• “Taking a history” and doing the PE

• Clinical evaluation [ e.g. CAGE, Folstein

MMSE, peak flow]

• Ordering, interpretation, and performance

of tests [e.g. CAT, MRI, ETT, PFTs]

• Procedures [ e.g. colonoscopy, conscious

sedation, labor and delivery ]

• Patient education, counseling, discharge

instructions, preps, written materials

E Hardt 1988

Clinical Issues II

• Consent for treatment/procedures/studies

• Follow-up of test results, appointment

compliance

• Medication compliance, adverse drug

reactions, allergies

• Cost containment, managed care

• Risk management, medical errors,

standards of care

• Doctor-patient relationships, patient

satisfaction

E Hardt 1988

Research Data and

Advocacy

Needed to change attitudes of

law and policy makers,

remodel provider behavior

and clinical systems, establish

credibility for interpreters.

Do We Have Health Care

Disparities related to

Language Barriers?

How big are they? For what

groups? In what areas? How do

we document them? What are

the costs? What can be done?

Who should be doing it?

Selected Research Issues

• Inclusion of potential LEP subjects

• Translation and validation of instruments

• Research infrastructure and personnel,

information systems

• Definitions [ PLINE, NES, LEP; “interpreters”

and translators ] and data collection methods

• Role of IRBs

• Research agenda

• Budgets and funding; involvement of

Interpreter Services

E Hardt 2005

The Exclusion of Non-EnglishSpeaking Persons from Research

• Survey of 172 responding researchers on

provider-pt relations

• Only 22% included LEPs who were potential

subjects

• Reasons for exclusions:

–

–

–

–

didn’t think of it

translation issues

staffing issues

no potential LEP subjects

Frayne SM et al J Gen Intern Med 1996

PROVIDER MAY NOT [OCR]:

• Provide service to LEP clients that are more

limited in the scope or that are lower in quality

than those provided to other persons

• Subject a LEP client to unreasonable delays in

the provision of services

• Limit participation in program or activity on

the basis of English proficiency

• Provide services to LEP persons that are not

as effective as those provided to those who

are proficient in English

• Require a LEP client to provide and interpreter

or to pay for the services of an interpreter

VNS of Western MA:

OCR Action I

• July 1998 intake RN and supervisor refused

to accept referral of Spanish-speaking

diabetic because “she didn’t speak English

and had no one to interpreter for her at

home…” They claimed that this was “the new

policy caused by budget cuts…”

• Patient was a recipient of Medicare/Medicaid

• Case reported to OCR by RN on behalf of pt.

VNS of Western MA:

OCR Action II

• By November 1998 the VNS had entered into a

compliance agreement with the OCR:

– Services for LEP patients were restored

– VNS contracted with a telephone interpretation

agency and instructed staff re its utilization

– Bilingual staff were recruited and hired and

matched to patients when possible

– The VNS was deemed by the OCR to be once

again in compliance with Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 and eligible for federal money

Studies on Language

Barriers

• Satisfaction

• Access

•

•

•

•

Utilization of Health Care

Quality of Care

Costs

Interventions

Impact of Language Barriers on

Patient Satisfaction in an

Emergency Department

• Survey of 2333 pts in 5 urban academic EDs

• 15% NES (? LEP status)

• Overall satisfaction: 52% for NES vs. 71%

for ES

• Willingness to return: 86% for NES vs. 91.5%

for ES

• NES pts more likely to report overall

problems with care, communication and

testing

Carrasquillo O et al JGIM 1999

Effect of Spanish Interpretation

Method on Patient Satisfaction

• 233 Eng-speaking [ES] and 303 Span-speaking

[SS] pts in CO urban walk-in clinic, mean age 32

• 128 of SS seen by language concordant MD [LC]

• 59 SS used AT&T, 69 SS used family members,

47 SS used ad hoc interpreters

• Overall satisfaction was identical for ES, LC, and

AT&T at 77 % Vs 54 % for those using family

and 49% for those using ad hoc interpreters

Linda Lee et al, JGIM 2002

Patient Assessment of

Medicaid Managed Care

• Consumer Assessment of Health Plans

Study [49,327 PTs/14 states, 1999-2000]

• Linear regression model within/between

plans; telephone/mail survey in Eng & Span

• NES reported lower ratings of care [access,

timeliness, provider communication, staff

helpfulness, & composite]

• White NES and Hispanic Spanish-speakers

clustered in worse plans

• Most observed racial/ethnic difference in

ratings attributable to within plan variation

including those for NES Asians

Weech-Maldonado et al, JGIM 2004

Importance of MD Training in

Use of Interpreters in the OPD

• 158 MD questionnaires about last clinic visit

involving an interpreter [?type] at SFGH

• 85 % satisfied with ability to Dx and Rx; but

only 45 % satisfied with ability to educate

and empower the PTs about Dx, Rx, meds

• Previous training in interpreter collaboration

was associated with higher IS use and

better satisfaction with medical care

Karliner L et al, JGIM 2004

Studies on Language

Barriers

• Satisfaction

• Access

•

•

•

•

Utilization of Health Care

Quality of Care

Costs

Interventions

One in Five Have Gone Without Care When

Needed Due to Language Obstacles

19% Have Not sought care when needed due to language barrier

HQ11: In the course of the past year, how many times were you sick, but decided not

to visit a doctor because the doctor didn’t speak Spanish or have an interpreter?

Source: Wirthlin Worldwide 2002 RWJF Survey

Racial/Ethnic Differences in

Children’s Access to Care

• Data from 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

(MEPS)

• 6900 US children, 9% lacking usual source of care

• 6.0% of Whites, 12.5% of AAs, 17.2% of Hispanics

• For Hispanics, 40.7% were interviewed in Spanish,

59.3% were interviewed in English

• Hispanic LEPs 27% as likely as Whites to have

regular source of primary care

• No difference between English-speaking Hispanics

and Whites

Weinick RM et al Am J Public Health 2000

Slide 7

Smoking Cessation Counseling

Percent of current smokers counseled by physician to quit

100%

79%

82%

78%

68%

67%

59%

50%

39%

0%

Total

White

African

American

Hispanic

Asian

American

Hispanic

EnglishSpeaking

Source: The Commonwealth Fund 2001 Health Care Quality Survey.

Hispanic

SpanishSpeaking

Studies on Language

Barriers

• Satisfaction

• Access

• Utilization of Health Care

• Quality of Care

• Costs

• Interventions

Does a Physician-Patient Language

Difference Increase the Probability of

Hospital Admission?

• Prospective observational study of 653 adult [AP] and 79 pediatric

[PP] pts in the ED at NYU Med Center Queens

• 14.7% of APs and 12.7% of PPs preferred non-English [NES]

• 52% of NES APs and 17% of NES PPs used “interpreters”

• No trained or professional interpreters were used

• NES APs were more likely to be admitted than ES controls, [35%

vs. 21%, RR 1.70 {1.14-2.53}]. No difference for PPs.

• Difference persisted after multivariate analysis for age,

gender, acuity level, and presence of an “interpreter”.

Lee ED et al Acad Emerg Med 1998.

Effect of English Language

Proficiency on Length of Stay I

• Retrospective review of administrative data

on consecutive admissions to 3 major

Toronto teaching hospitals 1993-1999

• LOS differences analyzed for 23 medical

and surgical conditions [59,547 records]

and then meta-analysis of 220 case mix

groups [189,119 records]

• Similar analysis for in-hospital mortality

John-Baptiste A et al, JGIM 2004

Effect of English Language

Proficiency on Length of Stay II

• LOS for LEP patients longer for 7 of 23

conditions [unstable coronary syndromes and

chest pain, CABG, stroke, craniotomy,

diabetes, hip replacement, GI procedures]

• Differences range from 0.7 to 4.3 days

• Overall LEP LOS 6% longer [ approx 0.5 days ]

• No increased risk of in-hospital death

John-Baptiste A et al, JGIM 2004

Studies on Language

Barriers

• Satisfaction

• Access

• Utilization of Health Care

• Quality of Care

• Costs

• Interventions

Ethnicity as a Risk Factor

for Inadequate Emergency

Department Analgesia

• 139 pts with long bone fracture in UCLA ED

• 108 NHWs, 31 Hispanic (42% NES, ?LEP)

• Hispanics twice as likely to get no ED pain

Rx [OR 7.46; 95% CI, 2.22-25.02; p<0.01]

• NES status was borderline significant

predictor [OR 3.12; 95% CI, 0.98-9.83;

p=0.052]

Todd KH et al JAMA 1993

Understanding Instructions for

Prescription Drugs Those Prescribed

Medication

100%

97%

95%

67%

75%

50%

27%

25%

2%

0%

2%

No Interpreter Needed

Understood Instructions

2%

5%

Interpreter

Needed/Available

Did Not Understand

7%

Interpreter Needed

Not Available

No instructions Given

Source: Andrulis D, et al. What a Difference an Interpreter Can Make:

Health Care Experiences of Uninsured with Limited English Proficiency, March 2002

Quality of Diabetes Care for NonEnglish-Speaking patients: A

Comparative Study

• Retrospective cohort study of 622 diabetics, 93

LEPs

• Academic medical center and county hospital

• Virtually all LEPs (24 languages) arrived with

professional interpreters

• LEPs more likely to get

– 2 or more Hgb AlC per year

– 2 or more clinic visits per year

– 1 or more dietary consults

• No differences in other labs, complications, use of

other services, and total changes.

Tocher TM et al West J Med 1998

Studies on Language

Barriers

•

•

•

•

Satisfaction

Access

Utilization of Health Care

Quality of Care

• Costs

• Interventions

Language Barriers and Resource

Utilization in a Pediatric ED

• 2467 patients in an urban, academic

pediatric ED

• 12% LEP, 8.5% with LB with MD

• For cases with LB:

– higher test ($145 vs. $104)

– Longer ED stay (165 vs. 137 minutes)

• Analysis of covariance:

– LB accounted for $38 and 20 minutes

Hampers Pediatrics 1999 LC et al

Does the Use of Trained Medical Interpreters

Affect ED Services, Charges, and Follow-up?

• Retrospective chart reviews of 503 pts in Boston Med Ctr ED

• CC: CP/SOB, HA, ABD pain, pelvic pain/vag bleeding

• 66 Eng-speakers [ESPs], 63 Spanish, Haitian, Cape Verdean

pts using hospital interpreters [IPs], 374 LEP pts not using

interpreters [NIPs]

• NIPs had shortest ED stay [p .001] and fewest tests [p .04]

and prescriptions [p .03]

• IPs were more likely to make clinic follow-up and less likely

to return to the ED than NIPs [p .03]

• Among non-admitted pts, return visit ED charges and total

subsequent 30 day charges were reduced for IPs compared

to NIPs and ESPs.

Bernstein J et al. Journal of Immigrant Health 2002; 4: 171-176.

Language Barriers in Health

Care: Costs and Benefits of IS

• Follow up analysis of intervention study at

major HMO as it increased interpreter

services [IS]

• Average cost of IS per LEP member $234/yr

• For HMO overall, total costs averaged $0.20

per member per month

• Average cost of IS encounter $79 at the

time which can be expected to decline with

increasing efficiency

Jacobs E, et al. AJPH 2004; 94:366-369

Studies on Language

Barriers

•

•

•

•

•

Satisfaction

Access

Utilization of Health Care

Quality of Care

Costs

• Interventions

Effects of Interpreters on the

Evaluation of Psychopathology in

Non-English-Speaking Patients

• 2 Public hospitals in NYC with no official

interpreters

• 30 psychiatric interpreter-interviews daily

• Interpreters were other pts, friends, family, staff

• Open discussions with providers and bilingual

employees

• Content analysis of 8 audio-taped interviews

• Distortions resulted from interpreters’ poor

language skills, lack of psychiatric knowledge,

and attitudinal issues

Marcos LR Am J Psychiatry 1979

When Nurses Double as Interpreters:

Spanish-speakers [SS] in Primary Care

• 21 SS pts with first walk-in visit to primary care clinic

with untrained nurses used to interpret

• Transcripts revealed serious miscommunication that

affected understanding or credibility in 1/2 cases

• MDs resisted reconceptualization in face of

contradiction

• Nurse provided data expected clinically vs. actual

• Nurse interpretation reflected unfavorably on pts

• Pts used cultural metaphors incompatible with

Western clinical nosology not always interpreted

Elderkin-Thompson et al, Soc Sci Med 2001

Impact of Interpretation

Method on Clinic visit Length

• Time motion study of 613 visits to PCU in

RI with 28% LEP pts [90% Span-speakers]

• Interpreted pts spent longer in clinic [93.6

vs. 82.4] and w/ provider [32.4 vs. 28.o]

• Patients using telephone and patientprovided interpreters took longer; those

using hospital interpreters did not

• Authors calculated potential cost savings

of reduced telephone usage and more

efficient MD utilization in terms of potential

hospital interpreters hired

Fagan MJ et al JGIM 2003; 18: 634-638

Medical Interpreters Have

Feelings Too I

• Anonymous questionnaire of all 22

members of interpreter service of GRC

• 5 had exposure to severe trauma [war,

torture, detention, beatings]

• 7 reported more than 50 % of sessions

involved patients with exposure to

violence

• 5 frequently experienced difficult feelings

during interpreting sessions

Medical Interpreters Have

Feelings Too II

• 66 % had frequently painful memories

• 83 % reported seeing patients outside

of the consultation setting

• Interpreters expressed the need to talk

and share feelings after the session

with the medical doctor [83 %] or with

relatives or spouse [44 %]

Louton L et al Soz Praventivmed 1999

Mandates for Medical

Interpreter Services

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

CLAS Standards

Office of Civil Rights [ORC] position

State laws [26 states and increasing]

Regulatory and review organizations

(JCAHO, NCQA]

Risk management

Possible cost savings, market

opportunities

Outcomes, quality

Justice

Massachusetts ED Interpreter Bill

[Effective July 1, 2001]

• Section 25J. Every acute-care hospital shall

provide competent professional interpreter

services in connection with all emergency room

services and acute inpatient psychiatric services

provided to a non-English- speaker or person

who has difficulty in speaking or understanding

the English language.

• Section 3c. Any non-English- speaker who is

denied effective health care services by a health

care provider by reason of the provider’s not

providing competent professional interpreter

services should have a right of action in a

superior court.

• Governmental units are to reimburse the cost of

interpreters for any mandated provider.

Selected Issues re

Standards

• Documentation: language status of patient

•

•

•

•

in IS; interpreter utilization by site, shift,

language, etc.

Risk Management: informed consent, staff

education re expectations and availability

Clinical outcome measures including

satisfaction, utilization, and quality

indicators

Research inclusion and activity, related

budgets

Training activity for staff and interpreters;

notification of rights for patients

E Hardt 2005

Might Language Competence

Facilitate Cultural Competence?

• Skills training viz language may invite and

synergize with efforts to learn content and

change attitudes while starting with a less

threatening set of goals

• Interpreter Services Department often

catalyze/lead organizational efforts at CC

• Methodology of organization’s approach to

language-based disparities can model

approach to other areas of disparities and

growth potential

E Hardt 2005

References and Bibliography

• See NCIHC website [ National Council

on Interpreting in Health Care],

www. ncihc.org

• www.calendow.org for annotated

bibliography August 2003

• email me at: eric.hardt@bmc.org

Questions???