Doctor of Philosophy for the degree of

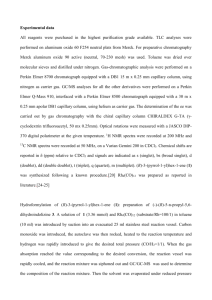

advertisement