: Green Infrastructure Case Studies

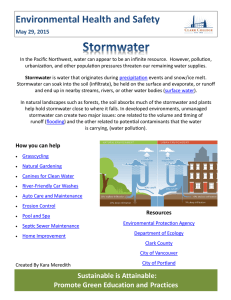

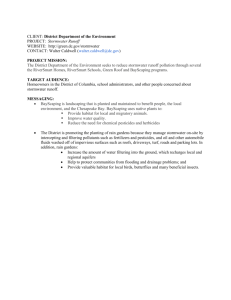

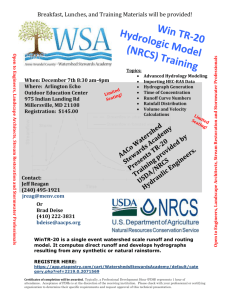

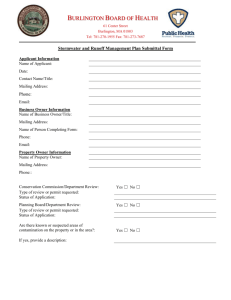

advertisement