War and the Growth of Government

advertisement

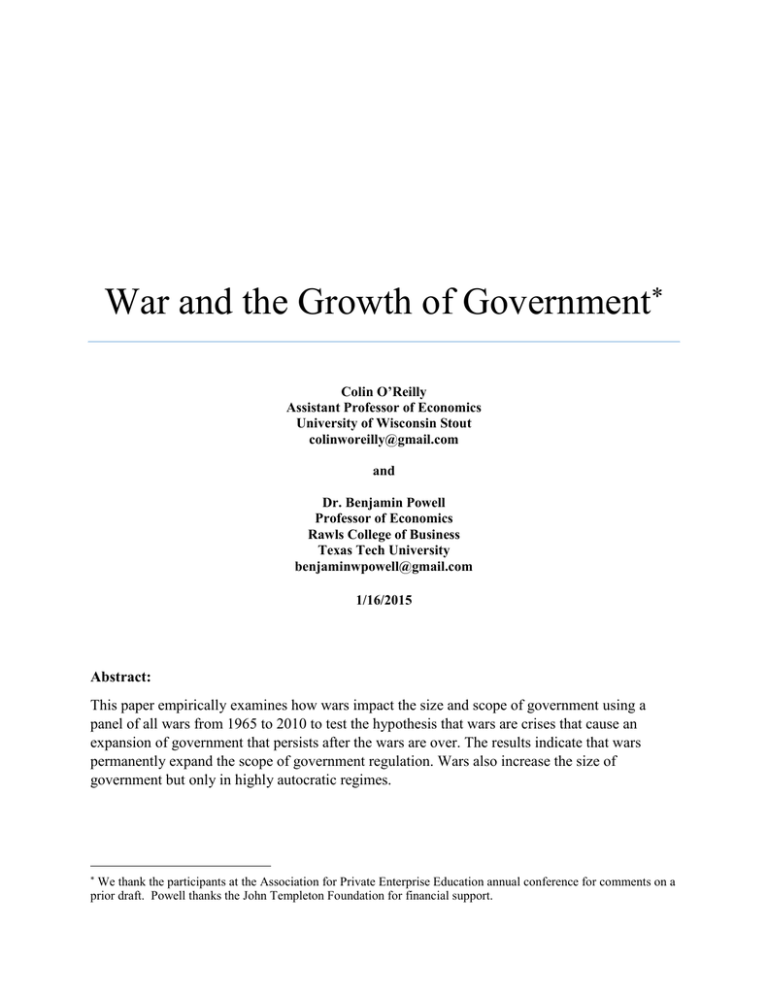

War and the Growth of Government Colin O’Reilly Assistant Professor of Economics University of Wisconsin Stout colinworeilly@gmail.com and Dr. Benjamin Powell Professor of Economics Rawls College of Business Texas Tech University benjaminwpowell@gmail.com 1/16/2015 Abstract: This paper empirically examines how wars impact the size and scope of government using a panel of all wars from 1965 to 2010 to test the hypothesis that wars are crises that cause an expansion of government that persists after the wars are over. The results indicate that wars permanently expand the scope of government regulation. Wars also increase the size of government but only in highly autocratic regimes. We thank the participants at the Association for Private Enterprise Education annual conference for comments on a prior draft. Powell thanks the John Templeton Foundation for financial support. JEL Codes: H11, H12, N40, P48 Key Words: War, Economic Freedom, Size of Government, Institutional Change 1 I. Introduction Wars destroy lives and capital while they are fought. But their impact on human suffering could last into the long run if they change a country’s institutional environment. Institutions are an important fundamental cause of economic development (Rodrik, Subramanian, & Trebbi, 2004) and a growing empirical literature supports the importance of an institutional environment of strong private property rights, a rule of law, and an environment of economic freedom for promoting long run growth (for surveys see: De Haan, Lundström, and Sturm (2006), Hall and Lawson (2014)). This paper examines how wars impact aspects of these institutions. There is a large political economy literature that explains the existence of government policies as the result of the power of vested interests.1 The role of ideas, though less formally modeled has also long been assumed to play a role. Keynes even claimed the primacy of ideas, “The ideas of economics and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist” (1936: 383). Crises impact both interests and ideas. Crises can lead to a change in policies “because prevailing interests may lose some of their legitimacy and because incumbents may be open to trying new remedies”(Rodrik, 2014: 203). In other words, crises can break the political equilibrium by changing the power of vested interests or changing peoples’ ideas about how the world works and what policies a government should adopt. War is one major form of a crisis that could impact the strength of interest groups and peoples’ ideas about the proper role of government. We empirically investigate how wars have changed the size and scope of governments over the last 40 years. There are theoretical reasons to believe that war could either increase or decrease the size and scope of government. Higgs (1987) argued that the U.S. government’s growth in the 20th century was caused by a “ratchet effect” stemming from crises. In times of crisis people demanded increased government services and interventions as their faith in the efficiency of 1 See Mueller (2003) for a survey. 2 markets is shaken or a larger government was needed to fight wars. According to Higgs, the scope of government is expanded during the crisis, but then after the crisis passes government does not revert all the way back to its pre-crisis size and scope (the ratchet effect). Higgs theorizes that both ideas and interests play a role in locking in the growth of government. Interests who benefit from the growth of government lobby to keep the new policies and individuals do not demand that the government revert to its original scope because they are more accustomed to the new role of the state. Alternatively, Olson (1982, 2000) argued that major disruptions and crises, such as wars, remove entrenched interest groups and clear the way for productive reforms. Olson theorizes that interest groups form over time, as they solve collective action problems, and demand more public goods and pursue the cartelization of the economy. This implies that over time rent seeking will expand the size and scope of government. A war can shatter these interest groups allowing reforms that shrink the size and scope of government. Both Higgs and Olson point to World War II for evidence in support of their theories. The case of the United States during WWII fits the narrative of the ratchet effect well, with government spending increasing drastically during the crisis of WWII and the Great Depression and contracting after the war ended. However, government spending and the size of the military never contracted to pre-WWII levels (Higgs, 1987).2 Conversely, the cases of post-war Japan and Germany are described better by Olson’s theory. Both Japan and Germany were plagued by economic stagnation and high inflation before WWII, but after massive destruction and the breakup of powerful interests, both countries had smaller governments and experienced impressive economic expansion (Coyne, 2008). A number of countries that have undertaken major liberalizations in the last twenty years, such as Ireland, New Zealand, and India, all experienced some form of financial crisis immediately prior to liberalization (Powell, 2008). Pitlik and Wirth go so far as to say, “A commonly shared wisdom among economists and political scientists is that crises promote the adoption of market-oriented reforms” (2003: 565). There are a few papers that have empirically examined whether financial crises impact the size and scope of government across a cross 2 Holcombe(1993) argues that after taking account of the trend toward government growth through the 20 th century that the depression/WWII ratchet is not statistically significant. 3 section of countries.3 Pitlik and Wirth (2003) examined how GDP growth crises and inflation crises impacted the economic freedom scores of 57 countries over five year periods from 1970 through 2000 and found that deep growth and inflation crises were significantly correlated with increases in economic freedom. Similarly, De Haan et al. (2009) find that banking crises are correlated with decreases in the size of government, as measured by the economic freedom index, over five year periods. However, Bologna and Young (2014) give us reason to doubt financial crises are correlated with increased economic freedom. They examine a panel of 70 countries from 1966 through 2010 using five different types of financial crises (banking, currency, inflation, internal debt, external debt) to see how they impact all five areas of the economic freedom index (size of government, legal structure and property rights, sound currency, freedom to trade internationally, and regulation) over 5, 10, and 40 year time periods. They also employ several weighting schemes to account for the timing and severity of the crises. Most of their results were statistically insignificant. However, they did find that financial crises tended to be associated with a decrease in that country’s government consumption to GDP ratio but they find crises are largely uncorrelated with other measures of economic freedom. However, over a 40 year period they do find that countries that spend more time in crisis tend to have less sound legal systems and protections for property rights.4 Although some work has been done on how various types of economic crises impact the size and scope of government, cross country statistical analysis of the effect of war on institutions is more limited. A World Bank study of civil conflict finds that institutional measures of economic policy, democracy, and civil liberties are, on average, worse than their pre-conflict level in the decade following the conflict (World Bank, 2003: 22). In a more rigorous study using control groups, Chen, Loayza, and Reynal-Querol (2008) study the pre- and postwar levels of macroeconomic variables for a large cross section of countries that experienced civil wars. 3 A few other studies Bruno and Easterly (1996), Drazen and Easterly (2001), and Lora and Olivera (2004) examine whether crises are associated with improved economic performance which may indirectly measure a change in the size and scope of government or policy. 4 Bologna and Young include intra-state conflicts (civil wars) as a contemporaneous control variable when investigating whether financial crises cause changes in freedom in subsequent periods. Thus, they do not investigate whether wars themselves, as crises, lead to changes in freedom in subsequent periods as our study does not do they examine other more numerous categories of war that we examine. 4 Although their focus is not the scope of government, they find that “government expenditure (as a percentage of GDP) increases 1 percentage point between the pre- and post-war periods;” (75) however, their results are not statistically significant leading them to conclude that there is “no discernable level change,” (71) in government expenditure. Though they do suggest a declining trend in government expenditure after civil war in absolute terms. Assessing these studies in their survey of the civil war literature Blattman and Miguel (2010) acknowledge that “The social and institutional legacies of conflict are arguably the most important but least understood of all war impacts.” In this study we contribute to understanding the institutional legacies of war. We also add to the literature that examines the causes of economic freedom. There is evidence that economic freedom is enhanced by fiscal decentralization (Cassette & Paty, 2010), more educated politicians (Dreher, Lamla, Lein, & Somogyi, 2009), and by the competitiveness of the political environment (Leonida, Maimone Ansaldo Patti, & Navarra, 2007). Djankov, McLiesh, Nenova, and Shleifer (2003), and Bjørnskov (2010) examined the determinants of legal institutions consistent with the economic freedom. This paper contributes to this literature by addressing how wars impact two specific components of economic freedom: the size of government and regulation. This paper tests whether war impacts the size and scope of government on a large cross section of countries using data on conflict events from 1965-2005. We test the impact of a war on the size and scope of government, comparing pre-war and post-war size and scope, while controlling for government’s size and scope prior to the war. A variety different types of wars are used as crisis events, including civil wars, international wars, internationalized wars and extra state wars. The next section describes our data and methodology. Section III contains our results. The final section concludes. II. Data and Methodology A panel spanning from 1965-2010 is constructed from two main data sources: the Economic Freedom of the World Annual Report (J. Gwartney, Lawson, & Hall, 2013) and the Correlates of War dataset (Sarkees, 2010). The full sample considers 124 countries over the period though the panel is unbalanced due to missing data on the size and scope of government for the early periods. All analysis is conducted on a panel broken into five year periods. 5 We use two components of the Economic Freedom of the World index (EFW) to capture the size and scope of government across countries: the “size of government” and “regulation.” The size of government component measures government consumption as a percent of total consumption; transfers and subsidies as a percent of GDP; the extent of private investment and business compared to government investment and state-owned enterprises; and the top marginal income and payroll tax rates. The regulation component includes three measures of credit market regulation, six measures of labor market regulation, and six measures of business regulation. The EFW data is based on a 0 to 10 point scale where 10 indicates the greatest economic freedom (smallest size/scope of government). The EFW data is available back to 1970 in five year intervals. As an additional measure of the size of government we use government expenditure as a percentage of GDP from the World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2014). We acknowledge that these variables measure only some aspects of the size and scope of government, and that many other dimensions of the size and scope of government are of interest but do not lend themselves to quantitative analysis. Data on violent conflicts including international wars, civil wars, and extra state wars is taken from the Correlates of War (COW) dataset. The COW dataset includes all wars from 1816 to 2007. A war is defined as “sustained combat, involving organized armed forces, resulting in a minimum of 1,000 battle related deaths” (Sarkees, 2010: 40). This definition, with some modifications, has become standard in the empirical economic and political science literature on violent conflict and does not substantially differ from the violence thresholds used in the Peace Research Institute Oslo dataset of wars (Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg, & Strand, 2002). The war event data is reshaped from event data to annual data and then paired with the EFW data on five year intervals. We use a dummy variable equal to 1 if a country experienced a war during a five year period. The four main war categories and their corresponding indicator variables are as follows: civil wars or intrastate wars (civil wars), international wars, extra state wars, and internationalized wars. Extra state wars corresponds to wars “in which a member of the interstate system is engaged in sustained combat outside its borders against the forces (however irregular or disorganized) of a political entity that is not a member of the state system” (Sarkees, 2010: 63). The COW dataset most often codes wars as extra state in cases of colonial 6 or imperial wars.5As an example of an extra state war, in 1991 Turkey engaged in combat with the Kurdish PKK group which was located inside of Iraq. This is not coded as an international war since Turkey was not engaged in conflict with state of Iraq, and it is not coded as an intrastate conflict since the conflict did not occur within the borders of Turkey (Sarkees, 2010: 327). International wars are conflicts between two members of the interstate system, whereas a war is coded as internationalized when an outside state intervenes in an intrastate conflict. For example, the Third Somalia War is classified as an intrastate conflict because the Somali government was fighting rebel groups. However, in 2007 the United States and Ethiopia intervened in this war, causing the war to be “internationalized” (Sarkees, 2010: 480). For the purposes of this study, states conducting the intervention, the United States and Ethiopia in this example, are coded as being engaged in an international conflict, as well as, an internationalized conflict for the period; thus internationalized conflicts are subset of international conflicts. The coding for Somalia is not effected by the intervention, Somalia is coded as experiencing an intrastate war in 2007. Note that there are many cases when a country is experiencing multiple types of war during the same five year period, in these circumstances dummy variables are equal to one for multiple war categories. Finally, the variable War is an indicator equal to one if a country experiences any type of war during the corresponding period. Of the 124 countries in our sample 60 experienced wars of some type. Of these 60 countries, 34 experienced civil wars and 45 experienced international wars. Many countries experienced multiple wars and even multiple types of wars over the sample period. For instance, Nigeria experienced a civil war in the 1985 and 1990 periods and then was engaged in an international war during the 1995, 2000 and 2005 periods. Control variables including Net ODA as a percentage of GDP, the logarithm of real GDP per capita and military expenditure as a percentage of GDP are collected from the World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2014). The polity index of democracy and autocracy from 5 A more in-depth discussion of the typology of extra state wars can be found in Sarkees (2010). 7 the Polity IV dataset is also used a control variable (Marshall, Gurr & Jaggers, 2013). Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. (Table 1) To test the effect of wars on the size and scope of government we estimate the following equation: 𝐺𝑜𝑣𝑡𝑡+1 − 𝐺𝑜𝑣𝑡𝑡−1 = 𝛽1 𝑊𝑎𝑟𝑡−1 + 𝛽2 𝑊𝑎𝑟𝑖,𝑡 + +𝛽3 𝑊𝑎𝑟𝑖, 𝑡+1 + 𝛽4 𝑊𝑎𝑟𝑖, 𝑡 ∗ 𝑊𝑎𝑟𝑖,𝑡+1 + 𝛽5 𝜏 +𝛽6 𝑓𝑖 + 𝛽7 𝐺𝑜𝑣𝑡𝑖,𝑡−1 + 𝛽8 𝑋𝑖,𝑡 + 𝜀𝑖,𝑡 Where i indicates countries and t indicates five year time periods. The variable Govt indicates the size or scope of government as measured by the components of the EFW index or government spending as a percentage of GDP and 𝑊𝑎𝑟𝑡 indicates a dummy variable equal to one if a country is engaged in war during the period t. War in the prior period and in the following period are controlled for with 𝑊𝑎𝑟𝑡−1 and 𝑊𝑎𝑟𝑡+1 . An interaction between wars in period t and wars in period t+1 is included to account for wars that extend beyond period t. Period fixed effects, 𝜏, are included to account for any long term trends in the size or scope of government and country fixed effects, 𝑓𝑖 , are included to control for any omitted country characteristics6. The inclusion of time and countries fixed effects constitutes a difference-in-difference methodology. Finally, X is a vector of controls that vary over time. The inclusion of 𝐺𝑜𝑣𝑡𝑡−1controls for the initial size or scope of government at the outset of the time period when a war later occurred. The evolution of institutions is complex and not well understood. By controlling for initial levels of the size and scope of government we are implicitly controlling for these long run factors and enabling us to examine only the impact of having a war. The parameter of most interest is 𝛽2which measures the change in the size or scope of government from before the war began to five years after the war has ended. A negative 6 A hausman test rejects the random effects model. 8 estimated coefficient on the war variable, 𝛽2 < 0, indicates that a war in period t (1985-1990, for example) caused the size or scope of government to increase (the change from 1985 to 1995). III. Results a. The Size of Government To assess the impact of war on the size of government we estimate fixed effects models with Area 1 of the Economic Freedom of the World and government spending as a percentage of GDP as measures of the size of government, these results are presented in Table 2 and Table 3 respectively. All specifications include controls for war in the prior period, t-1, controls for war in the following period, t+1, as well as an interaction between war in period t and t+1. These variables are included to account for countries that experience many wars, or have an ongoing war. The coefficient on the main variable of interest, war, indicates the impact that a war has had on the size of government in a country that has experienced a war during the five year period, but is not experiencing war during the subsequent five year period. (Table 2 and Table 3) The baseline specification in Column 1 includes country fixed effects to account for all time invariant country characteristics, such as unobserved cultural an institutional factors. In addition the baseline specification includes time effects, to account for any long run trends in the size of government. Therefore, the baseline specification is a difference-in-difference approach to estimation. The coefficient corresponding to the war variable is negative when the Area 1 index is the outcome variable (indicating an increase in the size of government). Similarly the coefficient is positive when government spending as a percentage of GDP is the outcome. Though both results are consistent with the ratchet effect, a decrease in the index or an increase in government spending, neither estimate is statistically significant. This finding constitutes a null result of a ratchet effect regarding these specific measures of the size of government. Variables that changes over time, including the pre-war Polity IV score, Net ODA as a percentage of GDP and the log of pre-war GDP per capita are included in Columns 2 through 4. The inclusion of these controls does little to alter the conclusions from the baseline specification; we do not find a significant relationship between war and the size of government. When the outcome variable is the size of government index the inclusion of control variables reduces the size of standard errors, though the point estimate on war is still statistically insignificant. The 9 final Column adds pre-war military expenditure as a percentage of GDP as a control which reduces the sample size by about half since it is only available since 1980. Estimates are still insignificant when military expenditure is included. Despite point estimates of the expected sign, we find no significant evidence that the size of government is affected by experiencing war. We will investigate the possibility of a conditional relationship in subsection e. Certainly there are many aspects to the size of the government that we are not able to measure, thus the lack of a significant result should be viewed as a null result, not as a rejection of the Higgsian ratchet for the size of government. b. The Scope of Government Fixed effects estimates of the effect war on the scope of government are presented in Table 4, with the baseline specification in Column 1 and control variables are added in subsequent columns. The index of the scope of government measures the absence of regulation, thus larger values mean a smaller scope of government. In the baseline specification the coefficient on war is -.29, and is statistically significant at the five percent level. Therefore, war is associated with an increase in the scope of government. The estimated effect is stable when control variables are added in columns 2 through 4, increasing slightly to -.30. The results are even robust, though less precisely estimated, to the inclusion of military expenditure as a percentage of GDP, which restricts the sample to wars occurring after 1980. The effect of -.30 is an economically meaningful change in the scope of government given that the standard deviation of the regulation index is 1.36. Further, the dependent variable is the change in the scope of government over a period of 10 years. The average change in the scope of government regulation over a 10 year period is .57 with a standard deviation of .93. Thus a coefficient of -.30 represents of about a third of a standard deviation decline in improvement of the scope of regulation index. (Table 4) c. Outcome of the Conflict The ratchet effect may be contingent on the outcome of the conflict. In Tables 5 through 7 we re-estimate the most complete specification, with controls of every variable except military expenditure, but replace war with a variable that indicates if the war ended in a decisive loss or 10 decisive win. For each table Column 1 presents the results for a decisive loss and Column 2 for a decisive win7. (Table 5 and Table 6) Again, the results that correspond to the size of government yield the expected sign, but lack statistical significance. However, for the scope of government outcome the coefficient on loss in Table 7 is -.48 and highly statistically significant. The coefficient on win is -.11, but is not statistically significant. This is some indication that decisive losses of war are driving the main result of a war induced ratchet effect. However, the results for win and loss should be interpreted with care. Modern wars a rarely clear cut events, and defining a war as a win or a loss is inherently subjective. (Table 7) d. Type of Conflict The final three columns of Table 5 through 7 present results for different types of wars: interstate wars, civil wars and internationalized wars. Consistent with the results from Table 2, when considering the size of government the estimates are statistically insignificant. However, the coefficient is the largest and most precisely estimated for internationalized conflicts. Table 7 presents the results for the scope of government. Consistent with the previous results the coefficients are all negative and of a similar magnitude to the results in Table 4, however all estimates statistically insignificant regardless of the type of war chosen. The loss of statistical significance appears to be due to larger standard errors when considering only one type of war. Breaking the results down by the type of war does not provide any compelling evidence that a particular type of war is driving the main results. e. Democracy Interaction To investigate the possibility that the growth in government caused by wars is dependent on the political decision rules in a country we include an interaction between the instance of war 7 Many wars to not end in a decisive win or loss and are not coded as either. 11 and the Polity index of democracy and autocracy. Calculated from the interaction between the Polity IV index and the instance war, the marginal effects of war are presented in Table 8. Polity scores are listed down the left side of the table, with a -10 indicating the most autocratic and 10 indicating the most democratic decision rules. The effect of a war on the size of government as measured by Area 1 of EFW is statistically significant for the most autocratic counties. For countries with more democratic institutions the impact of war is positive but not significant, the effect of war becomes negative at a polity score of zero and becomes larger in magnitude as counties become more autocratic. The size of the effect of war ranges from -.30 to -.46 for polity scores ranging from -6 to -10. Therefore, the effect of war on the size of government is conditional on the degree to which decision rules are democratic. This explains the absence of a significant relationship when considering the unconditional effect of war in Table 1. The marginal effects of government spending over different measures of the polity index are presented in column 2. Though the marginal effects are not statistically significant for any level of the polity index, the point estimates indicate the largest increase in government spending for the most autocratic countries; this is consistent with the results from column 1. The conditional relationship between democratic institutions and the scope of government is the most compelling. The effect of war on the scope of government ranges from .12 for the most democratic countries to -.45 for the most autocratic countries. These results are significant that the 5% level for all polity scores below 2, which indicates institutions that have very few democratic elements. For the most autocratic counties, engaging in war is associated with half of a standard deviation lower improvement in the scope of regulation in the economy. The executive constraints built into democratic institutions appear to limit the extent of the ratchet effect. (Table 8) IV. Conclusion Crises can break existing political equilibria and allow for institutional change that was not previously possible. The existing cross-country empirical work examining the role of crises on institutional change has focused on economic crises. Although results of those studies vary, 12 in general they tend to indicate that if economic crises have an impact on institutions, it is the direction of liberalization and greater economic freedom. This study finds that, unlike economic crises, wars tend to be associated with an increase in the scope of government (decrease in economic freedom). We also find some evidence that wars expand the size of government in the most autocratic regimes. Paul Collier has described civil war as “development in reverse” (World Bank, 2003). This same description may apply to war in general. The scope of regulation score has been improving around the world at a rate of .57 over a span of two decades. Yet, if a country engages in war during that period the expected improvement in the index is only .27. Conflict is slowing the process of developing more free and open regulatory environment. Collier identified a cycle of low income leading to conflict and conflict leading to lower incomes; he dubbed this cycle “the conflict trap” (World Bank, 2003). Our results indicate that the deterioration of economic freedom may play a role in the conflict trap. If, as our results indicate, engaging in war actually erodes a dimension of economic freedom, we may have identified another channel through which Collier’s conflict trap is perpetuated. 13 References: Bjørnskov, C. (2010). How does social trust lead to better governance? An attempt to separate electoral and bureaucratic mechanisms. Public Choice, 144(1-2), 323–346. Blattman, C., & Miguel, E. (2010). Civil War. Journal of Economic Literature, 48(1), 3–57. Bologna, J. and A. Young (2014). Crises and Government: Some Empirical Evidence. Working Paper. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2313846 Bruno, M., & Easterly, W. (1996). Inflation’s Children: Tales of Crises That Beget Reforms. The American Economic Review, 86(2), 213–217. Cassette, A., & Paty, S. (2010). Fiscal decentralization and the size of government: a European country empirical analysis. Public Choice, 143(1-2), 173–189. Chen, S., Loayza, N. V., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2008). The Aftermath of Civil War. The World Bank Economic Review, 22(1), 63–85. Coyne, C. J. (2008). After war: the political economy of exporting democracy. Stanford, Calif: Stanford Economics and Finance. De Haan, J., Lundström, S., & Sturm, J.-E. (2006). Market-oriented institutions and policies and economic growth: A critical survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 20(2), 157–191. De Haan, J., J. Strum, and E. Zandberg (2009). The Impact of Financial and Economic Crises on Economic Freedom. In Gwartney & Lawson (Eds.), Economic Freedom of the World 2009 Annual Report. Vancouver: Fraser Institute. Djankov, S., McLiesh, C., Nenova, T., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Who Owns the Media? Journal of Law and Economics, 46(2), 341–382. Drazen, A., & Easterly, W. (2001). Do Crises Induce Reform? Simple Empirical Tests of Conventional Wisdom. Economics and Politics, 13(2), 129–157. 14 Dreher, A., Lamla, M. J., Lein, S. M., & Somogyi, F. (2009). The impact of political leaders’ profession and education on reforms. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(1), 169– Gleditsch, N. P., Wallensteen, P., Eriksson, M., Sollenberg, M., & Strand, H. (2002). Armed Conflict 1946-2001: A New Dataset. Journal of Peace Research, 39(5), 615–637. Gwartney, J., Lawson, R., & Hall, J. (2013). Economic Freedom of the World: 2013 Annual Report. Vancouver: Fraiser Institute. Gwartney, J., Lawson, R., & Holcombe, R. (1999). Economic Freedom and the Environment for Economic Growth. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) / Zeitschrift Für Die Gesamte Staatswissenschaft, 155(4), 643–663. Hall, J., & Lawson, R. (2014). Economic Freedom of the World: An Accounting of the Literature. Contemporary Economic Policy, 32(1), 1–19. Higgs, R. (1987). Crisis and leviathan: critical episodes in the growth of American government. New York: Oxford University Press. Holcombe, R. G. (1993). Are There Ratchets in the Growth of Federal Government Spending? Public Finance Review, 21(1), 33–47. Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest and money. United States: Macmillan Cambridge University Press. Leonida, L., Maimone Ansaldo Patti, D., & Navarra, P. (2007). Towards an Equilibrium Level of Market Reform: How Politics Affects the Dynamics of Policy Change. Applied Economics, 39(13-15), 1627–1634. Lora, E., & Olivera, M. (2004). What Makes Reforms Likely: Political Economy Determinants of Reforms in Latin America. Journal of Applied Economics, 7(1), 99–135. 15 Marshall, M., Gurr, T. & Jaggers, K. (2013). Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2012. Centre for Systemic Peace. Mueller, D. C. (2003). Public Choice III. Cambridge University Press. Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations: economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities. New Haven: Yale University Press. Olson, M. (2000). Power and prosperity: outgrowing communist and capitalist dictatorships. New York: Basic Books. Pitlik, H., & Wirth, S. (2003). Do crises promote the extent of economic liberalization?: an empirical test. European Journal of Political Economy, 19(3), 565–581. Powell, B. (2008). Making poor nations rich: entrepreneurship and the process of economic development. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Economics and Finance, Stanford University Press. Rodrik, D. (2014). When Ideas Trump Interests: Preferences, Worldviews, and Policy Innovations. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(1), 189–208. Rodrik, D., Subramanian, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Institutions Rule: The Primacy of Institutions Over Geography and Integration in Economic Development. Journal of Economic Growth, 9(2), 131–165. Sarkees, M. R. (2010). Resort to war: a data guide to inter-state, extra-state, intra-state, and non-state wars, 1816-2007. Washington, D.C: CQ Press. World Bank. (2003). Breaking the conflict trap: civil war and development policy. (P. Collier, Ed.). Washington, DC : [New York]: World Bank ; Oxford University Press. World Bank. (2014). World Development Indicators. Retrieved February 22, 2014, from http://www.worldbank.org 16 Table 1: Descriptive Statistics Variable Change in Size of Government-Area 1 Government Spending/GDP Change in Scope of Government-Area 5 Net ODA/GDP Source Gwartney, Lawson, & Hall (2013) World Bank (2014) Polity IV Marshall, Gurr & Jaggers, (2013) World Bank (2014) Ln GPD per capita Gwartney, Lawson, & Hall (2013) World Bank (2014) Obs. Mean/ Standard Proportion Deviation 771 0.34 1.50 689 0.57 0.93 856 0.27 6.89 2130 4.03 8.23 1296 0.22 7.31 1516 8.35 1.23 Military World Bank (2014) 719 2.73 Expenditure/GDP Note: Each observation represents a five year period. 3.05 17 Table 2: Size of Government- Area 1 of EFW (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) -0.0354 (0.1464) 0.1277 (0.1712) 0.2339 (0.2047) -0.0471 (0.1096) -0.9855*** (0.0469) 0.0161 (0.0144) -0.0113 (0.0154) -0.5808*** (0.1693) 0.3264 (0.2808) 0.6223 (0.3753) -0.2260 (0.4120) 0.1033 (0.1938) -1.2455*** (0.0758) 0.0587** (0.0243) 0.0136 (0.0180) -0.2835 (0.3685) -0.0451* (0.0267) VARIABLES War(t) War(t+1) War(t)*War(t+1) War(t-1) Gov. Size (t-1) Polity(t-1) Net oda Lngdpcap(t-1) Milexpcap(t-1) -0.0965 (0.1405) 0.0262 (0.1847) 0.1766 (0.2057) -0.0056 (0.1078) -0.9636*** (0.0478) -0.0933 (0.1373) 0.0424 (0.1795) 0.1694 (0.2004) 0.0127 (0.1082) -0.9616*** (0.0475) 0.0245 (0.0151) -0.1047 (0.1400) 0.0389 (0.1793) 0.1750 (0.2003) -0.0024 (0.1126) -0.9591*** (0.0486) 0.0236 (0.0154) 0.0111 (0.0170) Observations R-squared Number of countries 771 729 722 682 298 0.635 0.6398 0.640 0.654 0.709 124 118 117 110 108 Robust standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 Note: These are the results of a fixed effects regression with county and period fixed effects are included. 18 Table 3: Size of Government- Gov. Spending/GDP (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) VARIABLES War(t) War(t+1) War(t)*War(t+1) War(t-1) Gov/GDP(t-1) Polity(t-1) Net oda Lngdpcap(t-1) Milexpcap(t-1) 0.0818 (0.7174) 0.9150 (1.2390) 0.8444 (1.1694) -0.9697*** (0.0887) 0.2280 (0.4365) 0.3697 (0.7249) 1.3789 (1.2811) 0.3276 (1.1889) -0.9670*** (0.0923) 0.2374 (0.4275) 0.0757 (0.0604) 0.4961 (0.7448) 1.4127 (1.2740) 0.2578 (1.1940) -0.9594*** (0.0884) 0.3490 (0.4251) 0.0730 (0.0597) -0.1017 (0.0799) 0.2706 (0.7328) 0.8521 (1.2988) 0.0945 (1.2926) -0.9290*** (0.0948) 0.4507 (0.4158) 0.1230*** (0.0469) -0.0107 (0.0617) 1.6141* (0.8740) 0.3029 (0.6397) 0.1003 (0.7104) -0.2166 (0.8750) -0.9533*** (0.0786) 0.3472 (0.3861) 0.1408** (0.0672) -0.0202 (0.0604) 0.0063 (0.8330) 0.2947*** (0.0990) Observations R-squared Number of countries 755 709 709 684 305 0.552 0.554 0.559 0.539 0.657 137 129 129 125 119 Robust standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 Note: These are the results of a fixed effects regression with county and period fixed effects are included. 19 Table 4: Scope of Government (Regulation) - Area 5 of EFW (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) VARIABLES War(t) War(t+1) War(t)*War(t+1) War(t-1) Regulation(t-1) Polity(t-1) Net oda Lngdpcap(t-1) Milexpcap(t-1) -0.2934** (0.1188) -0.3400** (0.1644) 0.2412 (0.2015) 0.0262 (0.0866) -0.9657*** (0.0465) -0.2966** (0.1149) -0.3453** (0.1608) 0.2387 (0.1963) 0.0385 (0.0917) -0.9814*** (0.0462) 0.0209 (0.0142) -0.3046*** (0.1146) -0.3478** (0.1609) 0.2415 (0.1961) 0.0309 (0.0934) -0.9819*** (0.0476) 0.0212 (0.0146) 0.0057 (0.0067) -0.2961** (0.1261) -0.3203* (0.1784) 0.2666 (0.2051) 0.0018 (0.1040) -0.9763*** (0.0479) 0.0197 (0.0147) 0.0061 (0.0070) -0.1248 (0.1375) -0.2841* (0.1473) -0.3338* (0.1911) 0.4422** (0.2170) -0.1272 (0.1004) -1.1658*** (0.0578) 0.0208 (0.0160) -0.0054 (0.0124) -0.6762*** (0.2449) -0.0465*** (0.0110) Observations R-squared Number of countries 689 653 646 614 298 0.535 0.547 0.549 0.550 0.739 123 117 116 109 107 Robust standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 Note: These are the results of a fixed effects regression with county and period fixed effects are included. 20 VARIABLES War(t) War(t+1) War(t)*War(t+1) War(t-1) Gov. Size(t-1) Polity(t-1) Net oda Lngdpcap(t-1) Observations R-squared Number of countries Table 5: Size of Government- Area 1 of EFW (War Types) (1) (2) (3) (4) Loss Win Inter Civil (5) Intervention -0.1834 (0.1845) 0.3781 (0.2435) 0.7165 (0.5193) -0.1693 (0.1302) -0.9847*** (0.0464) 0.0191 (0.0147) -0.0077 (0.0155) -0.5558*** (0.1563) -0.2214 (0.1502) -0.0932 (0.1719) 0.4370 (0.2666) 0.0235 (0.1673) -0.9866*** (0.0473) 0.0170 (0.0146) -0.0080 (0.0159) -0.5161*** (0.1647) -0.1558 (0.1249) -0.2341 (0.1586) 0.5393** (0.2525) -0.1788 (0.1227) -0.9870*** (0.0477) 0.0158 (0.0147) -0.0076 (0.0153) -0.5162*** (0.1640) -0.0324 (0.1250) -0.0181 (0.1563) 0.1270 (0.2354) -0.0973 (0.1147) -0.9848*** (0.0471) 0.0165 (0.0147) -0.0086 (0.0156) -0.5398*** (0.1683) -0.1830 (0.2000) 0.1637 (0.2848) 0.5149 (0.3141) -0.0698 (0.1448) -0.9852*** (0.0467) 0.0187 (0.0144) -0.0110 (0.0152) -0.5415*** (0.1596) 682 0.655 110 682 682 682 682 0.653 0.650 0.656 0.651 110 110 110 110 Robust standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 Note: These are the results of a fixed effects regression with county and period fixed effects are included. 21 VARIABLES Table 6: Size of Government – Gov. Spending/GDP (War Types) (1) (2) (3) (4) Loss Win Inter Civil War(t) War(t+1) War(t)*War(t+1) War(t-1) Gov/GDP(t-1) Polity(t-1) Net oda Lngdpcap(t-1) Observations R-squared Number of countries 0.3719 (0.6967) -0.5035 (1.1358) -0.8738 (1.9662) 0.7963 (0.8010) -0.9227*** (0.0952) 0.1138** (0.0452) -0.0025 (0.0627) 1.7782* (0.9054) 0.3048 (0.7131) 1.7500 (1.4291) -1.9049 (1.4617) -0.0072 (0.5812) -0.9199*** (0.0934) 0.1211*** (0.0462) -0.0047 (0.0625) 1.6855* (0.8672) 0.5109 (0.7509) 1.8601 (1.4782) -1.0011 (1.4846) 0.4247 (0.5423) -0.9317*** (0.0956) 0.1182** (0.0472) -0.0096 (0.0590) 1.6340* (0.8918) -0.4986 (0.6495) 0.0450 (0.9106) 0.8362 (0.9613) 1.1733* (0.6204) -0.9290*** (0.0957) 0.1211*** (0.0460) 0.0019 (0.0618) 1.7478* (0.9102) (5) Intervention 1.0831 (0.9838) 1.3703 (0.9677) -1.9562* (1.1775) 0.3098 (0.6458) -0.9271*** (0.0959) 0.1229*** (0.0468) -0.0096 (0.0591) 1.6990* (0.9211) 684 0.537 125 684 684 684 684 0.540 0.542 0.538 0.537 125 125 125 125 Robust standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 Note: These are the results of a fixed effects regression with county and period fixed effects are included. The title for each column represents a different type of war. 22 VARIABLES War(t) War(t+1) War(t)*War(t+1) War(t-1) Regulation(t-1) Polity(t-1) Net oda Lngdpcap(t-1) Observations R-squared Number of countries Table 7: Scope of Government – Area 5 of EFW (War Types) (1) (2) (3) (4) Loss Win Inter Civil -0.4745*** (0.1649) -0.5356** (0.2193) 0.2139 (0.4680) 0.1161 (0.1411) -0.9732*** (0.0459) 0.0176 (0.0137) 0.0046 (0.0077) -0.1362 (0.1430) -0.1062 (0.1366) -0.2337 (0.1615) 0.2867 (0.2365) -0.1071 (0.1307) -0.9684*** (0.0465) 0.0188 (0.0145) 0.0038 (0.0075) -0.1680 (0.1409) -0.2025 (0.1675) -0.3571* (0.1831) 0.1466 (0.2501) -0.0296 (0.0994) -0.9769*** (0.0452) 0.0200 (0.0147) 0.0043 (0.0071) -0.1262 (0.1410) -0.2561 (0.1605) -0.4448** (0.2004) 0.5128* (0.2735) 0.0974 (0.1607) -0.9775*** (0.0448) 0.0204 (0.0145) 0.0048 (0.0072) -0.1369 (0.1392) (5) Inter -0.0779 (0.1882) -0.4794*** (0.1284) 0.4853* (0.2487) 0.1109 (0.1494) -0.9628*** (0.0447) 0.0199 (0.0145) 0.0048 (0.0069) -0.1231 (0.1366) 614 0.55 109 614 614 614 614 0.54 0.55 0.55 0.55 109 109 109 109 Robust standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 Note: These are the results of a fixed effects regression with county and period fixed effects are included. 23 Table 8: Interaction between War a Polity IV (1) (2) (3) Polity IV Score Gov. Size Gov/GDP Regulation -10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10 -0.4562** (0.2293) -0.3775* (0.1979) -0.2987* (0.1709) -0.2199 (0.1506) -0.1411 (0.1399) -0.0624 (0.1410) 0.0164 (0.1538) 0.0952 (0.1756) 0.1740 (0.2036) 0.2527 (0.2356) 0.3315 (0.2701) 0.6392 (1.1957) 0.5446 (1.0781) 0.4500 (0.9644) 0.3555 (0.8562) 0.2609 (0.7560) 0.1664 (0.6674) 0.0718 (0.5954) -0.0228 (0.5467) -0.1173 (0.5279) -0.2119 (0.5420) -0.3064 (0.5866) -0.4548** (0.2320) -0.4220** (0.2043) -0.3893** (0.1787) -0.3566** (0.1560) -0.3238** (0.1377) -0.2911** (0.1257) -0.2584** (0.1219) -0.2256* (0.1271) -0.1929 (0.1402) -0.1602 (0.1594) -0.1274 (0.1827) Observations 682 684 614 Standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 Note: This table reports the marginal effect of war across different values of the Polity IV index. Each column represents a different dependent variable. 24