Program and Policy Strategies to Promote Healthcare Quality for Children

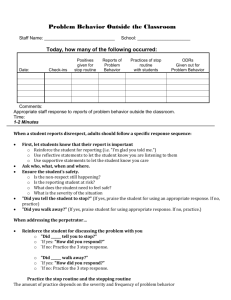

advertisement

Program and Policy Strategies to Promote Healthcare Quality for Children Lisa A. Simpson, MB, BCh, MPH, FAAP National Director, Child Health Policy, NICHQ Endowed Chair, Child Health Policy University of South Florida Today’s Popular Policy Platforms Pay for Performance Health Information Technology Consumer driven health care For each… – What do we know about use and/or its effectiveness overall? – What do we know of its use and/or effectiveness for children? Pay for Performance (P4P) Incentive programs that provide monetary bonuses to eligible participants linked to specific quality and/or efficiency standards established by the program Initiated by government agencies, employers & health plans to stimulate quality improvement (one of the earliest from Aetna in 1987) Financial rewards based on achievement related to – – – – evidence-based clinical quality of care measures patient satisfaction efficiency/productivity infrastructure of the practice (including use of information technologies) AMA, Physician Pay for Performance Initiatives, 2004. P4P Programs Average incentive payment around 1-5% of a physician’s total revenue from a given health plan (AMA, 2004) – in Anthem BC/BS (NH) in 2001, average bonus payment $1,183 and the highest bonus payment $15,320 – in IHA program, average group bonus about $200,000 and will cover 24,000 primary care physicians (200 physician groups & 7 million beneficiaries) 2004 survey findings: – Majority of programs were targeted to PCPs, confined to HMO, fully insured products with annual bonus incentives based on HEDIS performance measures – Dramatic growth: November, 2004: 84 programs w/ 39 million beneficiaries March 2005: 104 programs – By 2006, predicted to increase to 160 programs Baker & Carter, 2005 AMA, Physician Pay for Performance Initiatives, 2004 Key Trends in P4P Programs Product Spread: – Expansion to PPOs & Consumer Directed Healthcare products – Expansion to specialists with use of specialty-specific measures Changes in Measures: – – – – – Use of measures for positive savings (generic substitution & efficiency) Supplementing population-based HEDIS measures Use of scorecards and actionable results reporting to change behavior Use of performance results for public reporting Significant growth in health information technology adoption measures Changes in types of payments – Use of adjustable fee schedules instead of annual bonus payments – Return on investment analyses (i.e., what would have been the financial and clinical outcome in the absence of a P4P program?) Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services as a P4P market driver Baker & Carter, Provider Pay-for-Performance Incentive Programs: 2004 National Study Results, 2005. Landon et al, 2004 PP4P - Pediatric Pay for Performance Leapfrog compendium identifies 12 programs (out of 70) – 4 states (IA, RI, UT, WI) - target health plans – Rest target physicians – 3 BC/BS (IL, MA, MO) States’ use of quality information – Varies by product: HMO and PPO Rewarding Results Leapfrog Compendium Focus on: – – – – well visit (child and adolescent) immunizations appropriate antibiotic utilization asthma (self management plans or medication management) – IT. (not clear if applies to peds) – volume, timeliness, and quality of electronic encounter data New Leapfrog Hospital Rewards Program All short term acute care hospitals Five clinical areas including newborn care accounting for 33% commercial admissions & 20% commercial inpatient spending Newborn care measures include: – Neonatal mortality – NICU – Process of Care -- 80%+ adherence: antenatal steroids for certain high-risk deliveries – 3rd/4th degree lacerations – Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system – Leapfrog Quality Index (NQF Safe Practices) Factors in Determining Compensation Florida Child Health Provider, 2005 Not a Factor (%) Use of clinical IT Email consultation with patients Minor Factor (%) Major Factor (%) 71.5 23.2 5.3 No Yes, Health plan/HMO 2.1 Yes, Other 1.7 96.2 Note: sample size varies by question, overall N=1219 Effectiveness of Pediatric PFP Programs: RCT’s Citation (abbr.) Physicians/Practices Assigned (N) Focus Davidson (1992) Well-child Recommendations Enhanced FFS (40) Control (40) Higher reimbursement rates for all in FFS No Hillman (1999) Well-child Recommendations & Immunizations Bonus + Feedback (19) Feedback only (17) Control (17) Bonus based on rank & degree of improvement No (but all groups improved over time) Fairbroth er (2001) Childhood Immunizations Enhanced FFS (12) Bonus + Feedback (24) Feedback only (21) Bonus based on compliance rates Overall improvement in FFS & bonus groups Reward Differences Between Groups Today’s Popular Policy Platforms Pay for Performance Health Information Technology Consumer driven health care For each… – What do we know about use or its effectiveness overall? – What do we know of its use or effectiveness for children? Health Information Technology (IT) Adoption by Physicians Physicians either routinely or occasionally use: – 79% electronic billing – 59% electronic access to patients' test results either routinely or occasionally – 27% EMRs and electronic ordering of tests, procedures, or drugs – 21% have automated patient reminders regarding routine preventive care – 7% e-mail with other doctors – 6% electronic clinical decision support systems – 3% email with patients Top 3 reported barriers – costs of system start-up and maintenance – lack of local, regional, and national standards – lack of time to consider acquiring, implementing, and using a new system Audet et al, Medscape 2004 and Health Affairs, 2005 “Unique” Issues for Children Not so unique at the technical level Differences emerge in – Market availability – Policy focus – Adoption of HIT applications Child Health Provider Adoption of HIT Total & by Gender, Florida, 2005 Methods – Mailed survey (two waves) between March and May 2005 – All licensed primary care physicians (MD/DOs) and a 25% sample of ambulatory subspecialists – N=1219 child health provider respondents Primary care pediatrics, family medicine and pediatric subspecialists serving >0% children Child Health Provider Adoption of HIT Total & by Gender, Florida, 2005 Routine office computer use Routine PDA use Email use with patients Routine EHR use Total 80.2% 40.1% 18.0% 24.3% Male 81.2 44.5 18.6 26.5 Female 75.4 31.6 14.5 22.5 p value .046* <.001* .127 .186 Note: sample size varies by question, overall N=1219 Percent Adoption of HIT by Medical Training Florida Child Health Providers, 2005 Routine office computer use Routine PDA use Email use with patients Routine EHR use Primary Care Pediatrics 79.9 38.4 14.3 17.0 Family Medicine 78.4 42.2 21.9 26.8 Other 86.7 38.4 16.4 36.4 p value .052 .419 .005* <.001* Primary Care Note: sample size varies by question, overall N=1219 Adoption of HIT by Provider Age Florida Child Health Providers, 2005 Routine office computer use Routine PDA use Email use with patients Routine EHR use <40 79.8 40.2 11.5 27.9 40-59 81.8 42.5 20.8 26.9 60+ 67.9 29.3 12.4 17.1 p value .003* .029* .008* .081 Age (years) Note: sample size varies by question, overall N=1219 Adoption of HIT by Provider Race Florida Child Health Providers, 2005 Race Routine office computer use Routine PDA use Email use with patients Routine EHR use White 80.3 39.2 19.9 26.2 Black 77.8 47.7 13.3 21.4 Hispanic 81.5 41.2 15.2 20.0 Asian 79.4 37.9 9.4 23.1 Other/ Unknown 79.3 50.0 20.7 14.3 p value .982 .597 .059 .269 Note: sample size varies by question, overall N=1219 Adoption of HIT by Practice Size Florida Child Health Providers, 2005 No. of Physicians Routine office computer use Routine PDA use Email use with patients Routine EHR use Solo 76.0 34.6 17.3 17.7 2-9 79.0 39.9 17.5 22.4 10-49 91.5 52.2 20.8 43.9 50+ 97.4 68.8 32.4 64.9 <.001* <.001* .110 <.001* p value Note: sample size varies by question, overall N=1219 Adoption of HIT By Practice Type Florida Child Health Providers, 2005 Routine office computer use Routine PDA use Email use with patients Routine EHR use Singlespecialty 74.1 35.9 17.0 19.5 Multispecialty 91.1 51.4 23.4 41.4 <.001* .002* .100 <.001* Type p value Note: sample size varies by question, overall N=1219 Adoption of HIT By Medicaid Volume Florida Child Health Providers, 2005 Medicaid Providers Routine office computer use Routine PDA use Email use with patients Routine EHR use Low-volume 77.1 30.7 20.0 24.5 High-volume (at least 20% Medicaid) 81.8 44.4 13.5 22.0 p value .145 <.001* .028* .460 Note: sample size varies by question, overall N=1219 Today’s Popular Policy Platforms Pay for Performance Health Information Technology Consumer Driven Health Care For each… – What do we know about use or its effectiveness overall? – What do we know of its use or effectiveness for children? Consumer Use of Quality Information Consumer driven health care shifts more financial responsibility to consumers on the assumption that this will drive better decisions Several initiatives to publicly report performance – Medicare driven – State driven Having an abundance of information does not always translate into its use to inform choices All health care decisions – plan, provider, treatment requires the use of information that: – Includes technical terms and complex ideas – Compares multiple options on several variables – Requires the consumer to differentially weight the various factors according to individual values, preferences & and needs Information presentation has a significant effect on impact and use Hibbard & Peters, Annual Reviews of Public Health (2003) Where Consumers Find Quality Information Percent who say they would be "very likely" to do each to try to find health care quality information... Ask friends, family members or co-workers 65% Ask their doctor, nurse or other health professional 65% Go online to an Internet web site that posts quality information 37% 36% Contact the Medicare program (age 65+) Contact someone at their health plan, or refer to materials provided by the plan Order a printed booklet with quality information by phone, mail, or online Contact a state agency Refer to a section of the newspaper or magazine that lists quality information 36% 20% 18% 16% KFF/AHRQ/Harvard School of Public Health. Chart 7. National Survey on Consumers’ Experiences with Patient Safety & Quality Information, November 2004 (Conducted July7 – Sept 5, 2004) Consumer Exposure to Quality Information Percent who say they saw information in the past year comparing quality among... Health insurance plans 28% 23% Doctors Percent who say they saw information on ANY of the above... 2004 22% Hospitals 15% 2000 11% 9% 35% 27% KFF/AHRQ/Harvard School of Public Health. Chart 7. National Survey on Consumers’ Experiences with Patient Safety & Quality Information, November 2004 (Conducted July7 – Sept 5, 2004) Consumer Use of Quality Information Percent who say they saw quality information in the past year and used this information to make health care decisions... 19% 12% 2000 2004 KFF/AHRQ/Harvard School of Public Health. Chart 10. National Survey on Consumers’ Experiences with Patient Safety & Quality Information, November 2004 (Conducted July7 – Sept 5, 2005) Importance of Quality Ratings 76 72 2004 2000 1996 61 62 48 52 50 46 45 47 49 45 43 38 33 32 25 20 Surgeon who has treated friends/family Surgeon that is rated higher Plan recommended Plan highly rated by friends by experts Hospital that is familiar Hospital that is rated higher KFF/AHRQ/Harvard School of Public Health. Chart 7. National Survey on Consumers’ Experiences with Patient Safety & Quality Information, November 2004 (Conducted July7 – Sept 5, 2004) Parental Use of Quality Information Little research specifically looking at this CAHPS related research points to similarities Existing evidence points to even greater difficulties for children due to – Poverty – Low educational attainment – LEP Conclusions Current policy strategies have been less well thought out/tested in child health populations CHSR community has opportunity to develop more evidence on these questions