i di l Measuring Inappropriate Medical Diagnosis and Treatment in Survey Data:

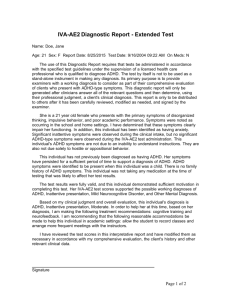

advertisement

Measuring Inappropriate Medical i i di l Diagnosis and Treatment in Survey Data: g y The Case of ADHD among School‐Age Children Child William Evans, Notre Dame M li d S dl M ill N h C li S Melinda Sandler Morrill, North Carolina State Univ. U i Steven Parente, Univ. of Minnesota R Research r h Question Q ti n Are children who are young relative to their classroom p peers more likely y to be diagnosed with ADHD? Pr i off R Preview Results lt ADHD iis an underlying d l i neurological l i l problem bl and incidence rates should not be dramatically different from one birth date to the next next. We W find fi d children hild b born jjustt b before f th the kindergarten eligibility cutoff date have a significantly higher rate of diagnosis (and treatment) than children born just after. 3 Pr i off R Preview Results lt Implications: I li ti Diagnosis is not solely based on underlying bi l i l conditions. biological diti Evidence of medically inappropriate di diagnosis. i Interpretation: Relative immaturity is being mistaken for ADHD. 4 Wh t is What i ADHD? According to the NIMH, ADHD Booklet: ADHD is a neurological g p problem. Symptoms include: • Difficulty staying focused • Difficulty controlling behavior • Hyperactivity Copyright (c) 1996 - 2005, WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved Wh t is What i ADHD? According to the NIMH, ADHD Booklet: “It is normal for all children to be inattentive,, hyperactive, or impulsive sometimes, but for children with ADHD,, these behaviors are more severe and occur more often.” Copyright (c) 1996 - 2005, WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved How ADHD Is Diagnosed? According to the NIMH, ADHD Booklet: “Often,, teachers notice the symptoms y p first,, when a child has trouble following rules, or q y ‘spaces p out’ in the classroom or on frequently the playground.” How ADHD Is Diagnosed? According to the NIMH, ADHD Booklet: Health p professionals consider whether the behaviors: happen more often in this child compared “happen with the child’s peers?” How ADHD Is Diagnosed? Diagnosis is often made without consulting a mental health specialist. Safer and Malever (2000): Maryland students g methylphenidate y at school had taking prescriptions from: Pediatricians: 63% Family Practitioners: 17% Psychiatrist: y 11% H is How i ADHD Tr Treated? t d? Non-medicinal treatment: behavioral therapy, counseling, psychotherapy Medication treatment: stimulants Most common form methylphenidate yp ((Ritalin)) Stimulants do not cure ADHD, only control the symptoms. 10 Medical Literature: Biological Effects of Stimulant Use Biological effects: Decreased appetite, pp insomnia, stomachache, headache, and dizziness (Ahmann et al., 1993). Increased heart rate & blood p pressure ((Nissen,, 2006). ) Longer term: may cause permanent changes in dopamine receptor function (Volkow and Insel, 2003). Tics (sudden repetitive movements or sounds) Copyright (c) 1996 - 2005, WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved NIMH Booklet: Side Effects of Stimulants 2007 FDA review lead to warning labels: Cardiovascular problems p Psychiatric problems such as hearing voices, having hallucinations,, becoming g suspicious p for no reason,, or becoming manic. (Atomoxetine, Strattera) Teenagers are more likely to have suicidal thoughts. Copyright (c) 1996 - 2005, WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved Imp rt n Importance Of children ages 7-17 in the United States: Approximately pp y 10% % have been diagnosed g with ADHD. Approximately 5% of children are currently taking prescription stimulants to treat ADHD. 13 M di l Lit Medical Literature r t r 1. ADHD diagnosis and treatment rates are rising. 2. Differential rates byy g gender, race, g geography, g p y SES, etc. (Cox et al. 2003, Castle et al. 2007, Visser et al. 2007, LeFever et al. 1999) 3. US has much higher rates than other countries. Our workk presents O t evidence id off systematic t ti inappropriate diagnosis of ADHD. 14 S i lS Social Sciences i n Lit Literature r t r Age at school entry effects: Older children are more prepared when entering kindergarten => better educational and behavioral outcomes. 15 S i lS Social Sciences i n Lit Literature r t r Age at school entry effects: Bedard and Dhuey (2006 QJE): cross-country comparisons, long-run long run effects. effects Datar (2006), Elder and Lubotsky (2009): age at school entry using eligibility cutoff dates as IV. Also: Dobkin and Ferreira (2007), Fertig and Kluve (2005), Goodman et al. (2003), Lincove and Painter (2006), McEwan and Shapiro p ((2009), ), Puhani and Weber ((2005), ), Angrist g and Krueger (1992), etc. Dhuey and Lipscomb (2009): Relative age and disability Papers looking at ADHD specifically: Elder and Lubotsky (2009), (2009) Elder (2010 forthcoming) forthcoming). 16 O r Contribution Our C ntrib ti n Using 3 detailed, large-scale health datasets: 1. Implement p a RDD model to verify y earlier work on relative age and ADHD diagnosis. 2 Apply methodology to stimulant use 2. use. Our O r results res lts provide pro ide evidence e idence of inappropriate medical diagnosis and treatment of ADHD among school-age children children. 17 D t Data Restricted Access National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) 1997-2006 ADHD diagnosis. Restricted Access Medical Expenditure Panel ( ) 1996-2006 Surveyy (MEPS) Prescription drug for ADHD. Private Claims Data Base 2003-2005 Prescription for stimulant. stimulant 18 D t : Sample Data: S mpl R Restrictions tri ti n Children age 7-17 on June 1st of survey year. Children born within 120 days of state x year specific kindergarten eligibility cutoff date. All estimates use sample weights and standard errors are clustered by state. 19 Relative Age and ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment Question: Are children born just after the cutoff date more likely y to be diagnosed g with and treated for ADHD? 20 ADHD Di Diagnosis i and dT Treatment R Rates 12% Percent 9.67% 8% 7.62% 6.45% 4 54% 4.54% 5 21% 5.21% 3.99% 4% 0% Diagnosis: NHIS Stimulant Rx: MEPS Days in relation to birthday cutoff Stimulant Rx: Pvt. claims [[-120,-1] , ] [[0,120] , ] F l ifi ti n T Falsification Tests t Threats to identification: Does exposure p to school (y (years of schooling) g) explain the higher risk of ADHD for relatively young children? Does stress induce higher levels of ADHD? No effect for: chicken p pox,, allergies, g , frequent q headaches, antibiotic use, or asthma medication use. 22 Falsification Tests: Other Childhood Disease Diagnosis Rates 80% 70% Perccent 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Respiratory Digestive Skin Allergy Hay Fever Frequent Allergy Allergy Headaches Days in relation to birthday cutoff [-120,-1] NHIS 1997-2006, Weighted Means [0,120] Chicken Pox Falsification Tests: Other Childhood Medication Usage Rates 40% 34.17% 34.85% 35% Perrcent 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 9.22% 9.31% 5% 0% Asthma Medication Days in relation to birthday cutoff Antibiotics [-120,-1] Private Claims Database, 2003-2005 [0,120] R r i n Fr Regression Framework m rk Ideally we would measure the effect of relative age g in classroom on ADHD diagnosis or treatment. Yi 0 1 X i 2Youngi \ i Young-for-grade may be endogenous, so use cutoff dates as an instrument instrument. 25 R r i n Fr Regression Framework m rk (2SLS) Problem: Grade in school not well measured in NHIS and MEPS,, not measured at all in private claims. If measurement error in grade-level causes attenuation bias in first-stage, 2SLS estimate will overstate the effect of age-for-grade. 26 .2 Fractio on Younge er than Med dian .4 .6 .8 First-Stage Relationship -100 -50 0 50 Num Days betw. Cut-off and Birth Date 100 Regression i Di Discontinuity i i Estimate i Define: z = birth date – kindergarten eligibility date Children “born after” (z ≥ 0) must wait to enter e te sc school, oo , so a are eo older de o on a average. e age Yi 0 1 X i 2 I ( zi 0) h( zi ) òi Regression i Di Discontinuity i i Estimate i Key Assumption: The true incidence rate of ADHD is continuous over dates of birth. If so, then the discontinuity in diagnosis and treatment across the kindergarten cutoff date is due to medically inappropriate diagnosis. 29 L lA Local Average r Tr Treatment tm nt Effect Eff t Note: Compliance with eligibility may be related to relative maturity. y The Th “t “treated” t d” sample l may nott b be representative of the average. 30 0 Fraction n with ADD/A ADHD Diag gnosis .05 .1 .15 5 .2 2 National Health Interview Survey, 1997-2006 -100 -50 0 50 Num Days betw. Cut-off and Birth Date 100 Notes: Data are from the restricted-access versions of the 1997-2006 National Health Interview Survey y (NHIS). ( ) The horizontal axis indicates bins for children born each number of days y from the kindergarten eligibility cutoff date. The dots are mean diagnosis or treatment rates for children born. The lines are from locally weighted regression interpolation. NATIONAL HEALTH INTERVIEW SURVEY (NHIS) O Outcome: ADD/ADHD Di Diagnosis i N= 35,343 Children Mean of Dependent Variable = 0. 0 0864 (1) Born After Cutoff Age Fixed Effects, G d R Gender, Race/Ethnicity /E h i i State and Birth Cohort Fixed Effects 1st Order Polynomial (2) (3) (4) -0.0204 -0.0209 -0.0206 -0.0208 ((.0050)) ((.0050)) (.0050) ( ) ((.0079)) X X X X X X MEDICAL EXPENDITURE PANEL SURVEY (MEPS) Outcome: Receiving Medication to Treat ADD/ADHD N = 31,641 for 18,559 Children Mean of Dependent Variable = 0. 0 0427 (1) Born After Cutoff Age Fixed Effects, G d R Gender, Race/Ethnicity /Eth i it State and Birth Cohort Fixed Effects 1st Order Polynomial (2) (3) (4) -0.0055 -0.0059 -0.0063 -0.0079 ((.0037)) ((.0034)) (.0034) ( ) ((.0058)) X X X X X X PRIVATE CLAIMS DATA Outcome: Prescription Claim for Ritalin or Other Drug for Treating ADD/ADHD N = 48,206 48 206 Observations for 22,371 22 371 Children Mean of Dependent Variable = 0.0584 (1) Born After Cutoff Demographics: Age (cubic), Gender State aand d Birth t Co Cohort ot FE 1st Order Polynomial (2) (3) (4) -0.0124 -0.0123 -0.0122 -0.0156 (.0021) (.0021) (.0030) (0.0057) X X X X X X S mm r Summary ADHD Diagnosis (NHIS), born after: 2.1 percentage points (24%) lower diagnosis risk ADHD Treatment (Private Claims), born after: 1 6 percentage point (27%) lo 1.6 lower er treatment risk ADHD Treatment (MEPS) (MEPS), born after: 0.6-0.8 percentage points (13-19%) lower treatment risk NHIS 2SLS: 5.9pp pp ((s.e. 2.3pp), pp), ~70% 35 H t Heterogeneity/ it / Specification S ifi ti Ch Checks k Explore sensitivity of main findings to: Heterogeneity in effects by: Narrowing window of sample. Higher order terms in zz. Specification changes. Limited dependent p variable model (p (probit)) Gender Race/ethnicity, when possible Age group (7-12 vs. 13-17) Falsification Tests: Other common childhood diseases and medications. H t r Heterogeneity n it in Effects Eff t “Reduced Form” coefficients rely on: Compliance p with the instrument. True age effect. Difficult to interpret relative differences. Example: Girls are more compliant but might have a smaller age effect. 37 Heterogeneity by Gender and Age NHIS (Diagnosis) Private Claims (Treatment) Boys Mean: 12.5% 0197 (0.0116) (0 0116) -00.0197 Mean: 8.0% 0.0218 0218 (0.0102) (0 0102) -0 Girls Mean: 4.7% -0.0209 (0.0088) Mean: 3.6% -0.0092 (0.0072) Age 7-12 Mean: 8.2% -0.0237 0.0237 (0.0107) Mean: 5.8% -0.0150 0.0150 (0.0080) Age ge 13-17 3 7 Mean: 9.3% -0.0158 0 0158 (0.0114) (0 0114) Mean: 5.8% -0.0154 0 0154 (0.0062) (0 0062) 38 C n l i n Conclusion Census: 53 million children ages 5-17 in U.S. on 6/1/2006. 2.1 pp = 1.1 million children received inappropriate ADHD diagnosis diagnosis. 1.6 pp = 800,000 children receiving inappropriate stimulant medication medication. 39 C n l i n Conclusion We find strong evidence of medically inappropriate pp p diagnosis. g Recognizing this pattern should: Improve I diagnostic di ti guidelines. id li Help to avoid excessive treatments with potentially serious short-term and long-term consequences. 40