Vulnerability of Species to Climate Change in the

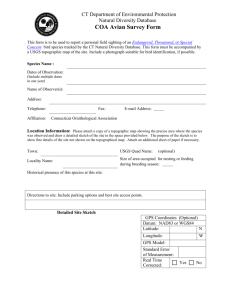

advertisement