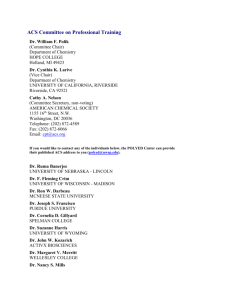

The American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program

advertisement

The American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program The American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) is a surgical quality improvement program that tracks a variety of data and outcomes across surgical procedures and specialties. Managed by the ACS, the ACS NSQIP has 526 member hospitals in the United States, varying in size (e.g., small, medium, large), populations served (e.g., pediatrics), and geographic location type (e.g., urban, rural). The ACS NSQIP is used by participating hospitals to: Measure the quality of surgical outcomes to improve overall patient care; Compare the quality of surgical outcomes against a national standard; and Identify critical quality improvement opportunities.1 Features The ACS NSQIP collects a range of data on patient characteristics and 30-day outcomes, including morbidities (or complications), such as surgical site infections (SSI) and pneumonia, as well as mortality and readmission rates. All outcomes are tracked from before surgery through 30 days after surgery to capture the full patient experience. In addition to these core data, the ACS NSQIP collects performance information in sub-specialties, such as gastrointestinal surgery, orthopedic surgery, pediatric surgery, and others.2 Data are collected by highly trained Surgical Clinical Reviewers (SCRs), who are employed by the hospital and trained entirely by the ACS. SCRs enter data directly into a secure, web-based platform at each hospital site. Every eight days, SCRs identify a sample of eligible patient cases based on information found in medical charts. These data are entered into the data collection platform and subsequently analyzed. Cases are risk-adjusted (i.e., account for differences in patient factors that might raise or lower their risk of adverse surgical outcomes, such as age or weight) and case mix-adjusted (i.e., account for the complexity of different procedures). These adjustments help ensure accurate comparisons between hospital sites.3,4 Importantly, all data fields have specific and rigorously-defined criteria, which helps ensure that high quality data are captured. Noteworthy Attribute Numerous studies detail the successes of the ACS NSQIP and justify its long-standing reputation for data quality and reliability. For example, the ACS NSQIP data are highly robust, and avoid misclassification or underreporting of outcomes—a result that is more common in administrative data reporting.5 One study compared data in a clinical database with those in the ACS NSQIP and found that the ACS NSQIP was better at predicting outcomes, including death, for higher-risk patients.6 This success is due in large part to the ACS NSQIP’s extensive efforts to ensure data quality, accuracy, and relevance to the needs of member hospitals.7 Key Contributions Improves Surgical Outcomes and Reduces Complications: Quality improvement activities leverage the ACS NSQIP data to pinpoint areas of opportunity. Two notable examples are: 1) reducing the prevalence of SSIs at the Surrey Memorial Hospital in Vancouver, British Columbia, an initiative which saved the hospital roughly $2.5 million over a two-year period, and 2) reducing length of patient stay by an average of 1.54 days in Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Michigan.8 To achieve such improvements, the two hospitals used the ACS NSQIP reports (e.g., best practices documents, semiannual report) and analyses to implement quality improvement programs. Generates Better Quality Measures: Given the increasing demand for higher-quality outcomes-based measures, hospitals and entities, such as the National Quality Forum, find value in and can endorse those measures developed from risk-adjusted ACS NSQIP data.9 Reduces Overall Morbidity: A study investigating the implementation of the ACS NSQIP in private hospitals found that site partic- The American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program ipation was associated with a reduction in overall patient morbidity following major and general vascular surgery over three years. Specifically, SSIs and renal complications were reduced.10 This observed fall in morbidity rates is thought to be the result of data being made available to providers; this feedback loop often acts as a catalyst for outcomes improvement activities in hospital sites.11 Saves Money and Provides Return on Investment: Costs associated with patient complications are burdensome to hospitals and patients, especially given the rise in bundled and capitated payment reform initiatives. One study found that a major surgical complication generates an average of $11,626 in extra costs per site.12 Another study concluded adverse surgical events raise the median cost of hospitalization for major surgical procedures up to five-fold.13 The ACS NSQIP has been shown to help reduce complications by identifying areas of concern within hospitals and providing resources for improvement. It is estimated that preventing just 15 or fewer complications per year per hospital could provide enough savings to cover the full cost of the ACS NSQIP participation.14 Looking Forward The ACS has committed to enhancing the ACS NSQIP by: 1. Expanding the number of participating hospitals; 2. Continuing to refine data collection processes and statistical methodologies; 3. Investigating cost and utilization in hospitals; and 4. Collaborating with national quality improvement initiatives. Visit http://site.acsnsqip.org/ for more information about the ACS NSQIP Citations 1 Key informant interview, Summer 2014. 2 Ibid. 3 The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, Common Ground for Health Care: ACS NSQIP Increases Quality, Reduces Costs, available at: http://site. acsnsqip.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/ACS-Policy1.pdf. Accessed on July 31, 2014. 4 Cohen, M. et al. “Optimizing ACS NSQIP Modeling for Evaluation of Surgical Quality and Risk: Patient Risk Adjustment, Procedure Mix Adjustment, Shrinkage Adjustment, and Surgical Focus.” Journal of the American College of Surgeons, Vol. 217:336-346, August 2013. 5 Davenport D., Holsapple C., and Conigliaro J. “Assessing Surgical Quality Using Administrative and Clinical Data Sets: A Direct Comparison of the University Health System Consortium Clinical Database and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Data Set.” American Journal of Medical Quality, Vol. 24(5):395-402, September-October 2009. Ibid. 6 Cohen, M. et al. “Optimizing ACS NSQIP Modeling for Evaluation of Surgical Quality and Risk: Patient Risk Adjustment, Procedure Mix Adjustment, Shrinkage Adjustment, and Surgical Focus.” Journal of the American College of Surgeons, Vol. 217:336-346, August 2013. 7 Ingraham A., et al. “Quality Improvement in Surgery: The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Approach.” Advances in Surgery, Vol. 44:251-267, October 2010. 8 The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, Key Studies, available at: http://site.acsnsqip.org/program-specifics/key-studies/. Accessed July 30, 2014. 9 Khuri S., Henderson W., Daley J., et al. “Successful Implementation of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in the Private Sector: The Patient Safety in Surgery Study.” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 248:329336. August 2008. 10 Ibid. 11 Dimick, J., et al. “Who pays for Poor Surgical Quality? Building a Business Case for Quality Improvement.” Journal of the American College of Surgeons, Vol. 202 (6): 933-7, June 2006. 12 Rowell, K., et al. “Use of National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Data as a Catalyst for Quality Improvement.” Journal of the American College of Surgeons, Vol.204 (6): 1293-1300, June 2007. 13 The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, Business Case, available at: http://site. acsnsqip.org/about/business-case/. 14 About the Authors Jessica Winkler, M.P.H., is a senior associate at AcademyHealth. She may be reached at jessica.winkler@academyhealth.org. Emily Moore is a student at University of Michigan School of Public Health. She was formerly a research assistant at AcademyHealth. Acknowledgements Sponsorship for this project was provided by The Kaiser Permanente Institute for Health Policy. We thank our partners at The Pew Charitable Trusts and all those interviewed for their contributions to these resources. A special thank you to Clifford Ko, Bruce Hall, Elizabeth Wick, and Laurent Glance for their review and assistance. This document represents a synthesis of information generated by a series of key informant interviews. Any views expressed are those of the interviewees.