24.00: Problems of Philosophy Prof. Sally Haslanger November 14, 2005

advertisement

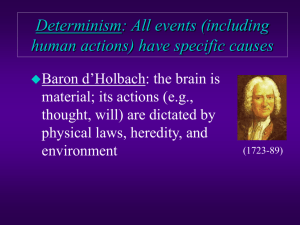

24.00: Problems of Philosophy Prof. Sally Haslanger November 14, 2005 Freewill III: Libertarianism I. Recap Deep-Self Compatibilism (Harry Frankfurt and others) Basic idea: Freedom is a matter of having an integrated self that governs how one acts. I act freely iff my actions are in the control of choices endorsed by my "deeper self" -endorsed that is by higher-order choices I have made, or by my values, or reflection, etc. Compatibility: As long as the causes of the action and the choices are of the right sort (in this version, they come from the deep self) the action is free. Avoidability is not required for freedom. Problem cases: weakness of will, early indoctrination, brainwashing, young children? Does it matter whether one's "deep self" itself issues from “wholesome” or "unwholesome" external causes, e.g., problematic upbringing, education, etc. Consider a case from Susan Wolf: JoJo is the son of Jo, an evil and sadistic dictator. JoJo is brought up to have fundamentally flawed values--that he endorses and identifies with. What's wrong with this picture? Why does JoJo seem unfree? Consider the legal definition of insanity: A person is sane if (1) he knows what he is doing, and (2) he knows that what he is doing is, as the case may be, right or wrong. As Wolf glosses it, …the desire to be sane is a desire to be controlled (to have, in this case, one's beliefs controlled) by perceptions and sound reasoning that produce an accurate representation of the world, rather than by blind or distorted forms of response. The same goes for the second constituent of sanity--only, in this case, one's hope is that one's values be controlled by processes that afford an accurate conception of the world. Putting these two conditions together, we may understand sanity, then, as the minimally sufficient ability cognitively and normatively to recognize and appreciate the world for what it is. (RR 10th edition, 441) “Sane Deep-Self” Compatibilism (Susan Wolf) I act freely iff my actions are controlled by choices endorsed by my "deeper self," & that deeper self is sane: I am able to appreciate what I am doing, and whether it is right or wrong. Basic idea: Freedom is a matter of having an integrated self governing how one acts, when that self has the capacity to make revisions/improvements in its beliefs, desires, values, etc. in light of information about the world (specifically information about what's right and wrong); in short, the integrated self must also have the capacity for self-correction. Compatibility: Same as Frankfurt case. Problem cases: actions out of sync with our "deep self", moral monsters II. Libertarianism 24.00 lecture notes 1 11/14/05 A. CHISHOLM AND AGENT CAUSATION Of our readings, Chisholm is the representative libertarian. Libertarians buy the basic incompatibilist argument: i) ii) iii) If x acts freely in performing action A, then x could have done otherwise. If x's performing A is determined, then x could not have done otherwise. So, if all acts are determined, then x never acts freely in performing action A. We’ve seen that both (i) and (ii) are controversial. So rather than focusing on the determinism side of the freewill dilemma, let's consider how denying determinism might open the possibility of freewill. Recall that the problem with the idea that indeterminism solves the problem is that if my action is uncaused or random, then it seems no more free than if it is determined by prior events. Random events are as much out of my control as those that are caused by prior conditions. So denying determinism offers little help. However, consider determinism again: DET) Whatever happens is determined by prior events. Chisholm points out that we may deny determinism, i.e. maintain that: IND) Some things that happen are not determined by prior events, without maintaining that the exceptions are uncaused or random. We need only claim that some events are not caused by other events. He suggests [In defending freewill] we must not say that every event involved in the act is caused by some other event; and we must not say that the act is something that is not caused at all. The possibility that remains, therefore, is this: We should say that at least one of the events that are involved in the act is caused, not by any other events, but by something else instead. And this something else can only be the agent—the man. (494) How is this supposed to work? Consider Aristotle's example: "...a staff moves a stone, and is moved by a hand, which is moved by a person." (Physics VII: 256a6-8). According to Chisholm, the moving of the staff and the hand are both events, and the hand-moving event causes the staff-moving event in the ordinary way (Chisholm refers to the causation between events as transeunt causation). Moreover, there is plausibly a brain event that causes the hand-moving event; again this is ordinary event causation. But, Chisholm maintains, if the action of moving the hand is free, then the brain event that causes the hand-moving event is not caused by another event, but is caused by the person or agent. (Chisholm calls such agent causation immanent causation.) I cause the neurons in my brain to fire in the way necessary to cause my hand to move, and there is no event which determines the firing of those neurons.1 So consider: Chisholm’s Libertarianism I act freely in performing an action A iff Chisholm allows that my causing the relevant neurons to fire is not in the full sense an action of mine— assuming that if it were I should be able to describe what I'm doing, etc.; but I certainly don't know enough about the brain to do that, and others (e.g., children) may cause such neural firings without even knowing that their brain is responsible for such behavior or that the brain contains neurons. 1 24.00 lecture notes 2 11/14/05 (i) I, rather than some prior event, am the cause of A (or of some event that directly causes A), and (ii) I could have performed an action other than A. Incompatibility: If determinism is true I couldn't have performed an action other than A, so I wouldn't satisfy (ii). Freedom: I am the source of my actions; they are not determined by prior events. Objections: Many have rejected the idea of agent causation because it appears mysterious and not fully compatible with our conception of the physical universe. For example, as Chisholm himself points out, if the firing of the hand-moving neurons is not caused by a prior event, the agent must bring it about that the firing occurs without there being anything happening in the agent. As Chisholm explains, "...the agent himself cannot be said to have undergone any change or produced any other event (such as "an act of will" or the like) which brought [the action] about." (496). This seems to leave agent causation somewhat mysterious, e.g., what distinguishes a case in which there is an agent and the occurrence of a random neural firing, and an agent causing a neural firing? Chisholm answers this question by simply pointing out that there is something mysterious even about event causation: what distinguishes an event A followed by an event B, and an event A causing event B? [Can you find any differences between the two sorts of cases? Are they equally mysterious?] But others find this response unconvincing. How, for example, does pointing to the agent as cause explain the event if there is nothing that the agent does to bring it about? B. FREEWILL AND INDETERMINISTIC CAUSATION Some philosophers are sympathetic to Chisholm's Libertarianism, but unsympathetic to agent causation. After all, it would seem that freedom does not require each an every free action to be an exception to determinism, for actions that are determined by our freely formed characters are themselves free. For example, if I am a good person and always choose to do the right thing, my choices are free as long as my having developed a good character wasn't entirely determined, but was something I am responsible for.2 So for some Libertarians, our focus should be on the potential freedom of "character building" acts. (On this topic, you might want to look at the Kane essay in RR.) Let’s consider a famous case described by Jean Paul Sartre: a young man during WWII is torn between joining the resistance, or staying home with his ailing mother. Suppose that in a case of such inner conflict it is indeterminate whether he will choose to join or stay home, and so indeterminate whether his brain will take path P (join) or path P* (stay home). Suppose he decides to join. His decision is not caused by his character (or by prior events in his brain), but is one of the events that forms his character. If then does join the resistance, his decision caused him to do so, even if it was indeterminate whether his brain would proceed down P. As a result, his actions are not random: they are caused but indeterminate. This view seems to have Remember the problem of evil? We considered the idea that an OOG God could give us all good characters, so we always do the right thing, and we could still be free. The Compatibilist would agree. The Libertarian might object, however, that our actions could be free, even if determined by our characters, but we are not free unless our characters themselves are freely formed. So if God determines that we have good characters we are not really free. 2 24.00 lecture notes 3 11/14/05 an advantage over Chisholm's because it does not postulate agent causation: my decision (a datable event, presumably) was the cause of my actions (via neural pathways). Consider then: Character-based Libertarianism I have free will iff in character building moments when I choose to perform action A: i) My choosing A was not determined by prior events; ii) My decision to perform A caused me to perform A (or to try to perform A). Indeterminacy: If determinism is true I couldn't have chosen an action other than A, so I wouldn't satisfy (i). Freedom: My decision in favor of A caused me to perform (or undertake to perform) A. Objection: How are we to understand the decision to perform A, e.g., the decision to join the resistance? By hypothesis, the decision was the cause of the (character building) action, but was the decision itself free? If in order to perform A freely, I have to freely decide to perform A, then does this generate an infinite regress? But if I didn't decide to perform A freely, then in what sense are my choice to join and my resulting actions free? C. FREEWILL AND STATISTICAL REGULARITIES What should we make of the claim that if an event is uncaused then it is “random”? In saying that it is “random” the suggestion seems to be that the event only has a certain chance of occurring. But mightn’t there be a enough of a correlation to make the event in question explicable, but still not determined? For example, suppose that my character, background, previous mental states, etc. didn’t determine that I would come to lecture today, but only made it likely. Perhaps there was a 90% chance that I would come to lecture, and a 10% chance that I would play goof off instead. Then it seems that there is room for my free will to make it the case that I attend, i.e., to make it the case that it’s one of the 90% cases rather than the 10% cases. One might argue that this shows the freewill dilemma does not capture the real issues. Recall the dilemma: 1. 2. 3. 4. If determinism is true, we can never do other than what we do; so we are not free. If indeterminism is true, then some events--possibly some actions--are random; but if they are random, we are not their authors. So we are not free. Either determinism or indeterminism is true. Therefore, we never act freely. The concern is that (2) is, at best, misleading. It doesn’t follow from that an event is not determined by prior events that it is random! Objection: Statistical regularities capture patterns in multiple cases. If there is a 75% probability that rain will occur, then in 3 cases out of 4 when conditions have been a certain way, rain has followed. In the actual case where rain occurs, however, it was determined to happen, i.e., some aspect of the conditions, an aspect that we perhaps were unable to predict, caused the rain to occur. So the fact that in some cases we can only predict what will happen with some degree of probability doesn’t show that the action that occurs is not determined. If the particular event really isn’t determined, then nothing prior to it made it happen, not the prior state of the world, not our free will, it just happened “out of nothing”. So the problem posed by (2) remains. 24.00 lecture notes 4 11/14/05 Where do we stand? Do you think that either Hard Determinism, Compatibilism, or Libertarianism offers a viable position? 24.00 lecture notes 5 11/14/05