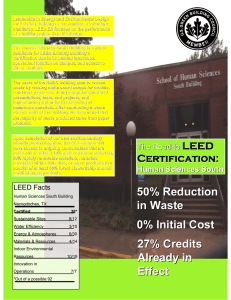

LEED CERTIFICATION Where Energy Efficiency Collides with Human Health

advertisement