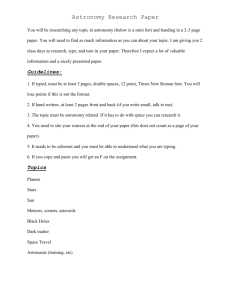

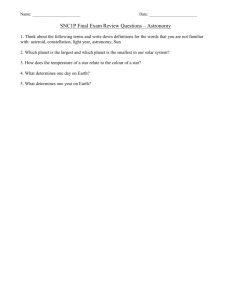

STATUS CONTENTS

advertisement