Each essay should be approximately 4000 words (around 8-10 pages,... not counting the separate Works Cited page

advertisement

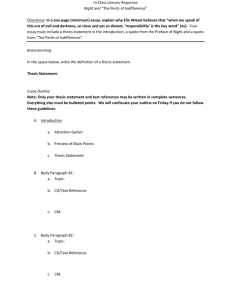

Assignment Sheet—Essay ENGL 4301.001 Each essay should be approximately 4000 words (around 8-10 pages, but if you end up going longer that’s OK), not counting the separate Works Cited page, and should have standard one inch margins, double spacing, and ordinary font size (Times New Roman 12 point is a good standard). Papers must use MLA documentation style (details in the MLA Handbook beginning on pg. 123. Each essay must include at least one quote from a minimum of four scholarly sources. Non-scholarly sources will not count. One of these sources may be an article or chapter from the McCarthy anthology we’ve read for class. You may choose which novel you focus on. I would recommend not trying to deal with more than two of McCarthy’s books in a modest-sized paper of this sort. You may write on the film if you like, but you’ll need to feel comfortable handling film criticism. Your essay must have a clear, specific thesis in the first paragraph that identifies the point you’re making about the text and explains how this helps us to understand the meaning of the text. In order to support this thesis, your paper should quote or paraphrase specific details from the text that illustrate your ideas; your paper should also provide specific analysis (close reading) of specific scenes that explains how each of those details helps to prove your thesis. In making your argument, the paper should clearly show how each passage contributes to your understanding of the work as a whole and/or how it illuminates one of the broader issues we discuss in class. (See pg 213-232 in MLA Handbook on how to cite works within your text.) You need at least one short quote from each of the scholarly sources on your works cited page. It’s OK if you find you disagree with the argument one of the scholarly sources is making—just clearly explain why you think the author is wrong. Generally speaking, a “story” is a work of fiction, a novel, or sometimes an autobiography. Non-fiction works are referred to as “essays” or “articles,” not “stories.” Authors (and often characters) are referred to by their full name the first time you mention them in your essay, and by last name thereafter, not by first name. General Essay Guidelines Title Give your paper a good, pointed title that in some way indicates your topic, such as "The Function of Color Imagery in Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony." Thesis Statement Give your paper a clear thesis statement of at least three sentences, at the end of your first paragraph, and make sure that this thesis states the interpretation your paper will argue for. Try phrasing your thesis as an argument you want to prove to an audience who may doubt you. For example, "There is a lot of controversy today over feminist interpretations of the Bible"--this would be an observation, not an argument. However, "Feminist interpretations of the Bible are highlighting a history that has been hidden for centuries," or "Feminist interpretations of the Bible are ridiculous because they ignore the patriarchal world from which Biblical writings originated," would be the beginning of a thesis. An expansion of that thesis might be "This essay will examine the ways in which the rich feminist history of the Bible has been suppressed...." Or "I will argue that modern feminists are simply seeing what they want to see, rather than what is actually present in Biblical texts." Please note the sentences beginning with “This essay will examine” and “I will argue that.” It is fine to use first person occasionally, especially when you’re making a statement/argument . Supporting Paragraphs, Topic Sentences, Quotations, etc. Each paragraph should have, if not a topic sentence, at least a clearly identifiable topic that supports the thesis you introduced in Paragraph 1. If you find yourself giving your reader a laundry list of scenes or ideas in each paragraph, or discover you’re summarizing the action or plot, you’ve probably got an incomplete thesis that doesn’t make an actual argument. Never just summarize what happens in the primary text. Remember that I have read the work or watched the film; I already know what happened. Your paper should present your interpretation of the work. If you find yourself structuring your essay according to the points made by some other author or according to what happens next in the book or film, you are probably doing summary and should stop immediately. One way to prevent summary is to imagine you've just seen a film (or read a novel) with some friends. You all walk out of the theater talking about the film. Would you need to explain to your friends who the main character was? Or what happened when X found out Y was lying? If you think your friends' response would be "Duh! I just watched the movie with you!" then you are summarizing, not analyzing. Avoid topic sentences that state a fact from the novel. Plot summary in the topic sentence tends to lead to plot summary in the rest of the paragraph. Make sure that every single quotation in the paper directly contributes to the argument. If it doesn't specifically support the paper's thesis, it shouldn't be in the paper. Make sure that every single interpretive point in the paper is supported by specific textual evidence. If the point is part of your argument, it must be supported by evidence in order to be persuasive. Always follow quotations with analysis and explanation to show how the passage supports your thesis. Integrate quotations into your sentences. Don't just drop them in there. Connect them to your sentence like this: 1. Set up the quotation with a topic sentence stating what you’ll be proving in the paragraph. The idea stated in this sentence should always have some clear relationship to your main thesis idea. 2. Lead into the quotation so as to make it part of your sentence. Often this can be as simple as using a phrase like "Smith writes, blah, blah, blah" but in some situations, you can also combine this step with step 1—as long as the sentence as a whole remains grammatically correct. Remember that some introductory phrases require a comma, while others require a colon; make sure the punctuation you use fits the sentence correctly. 3. Give the quotation or paraphrase correctly and in the proper format, including documentation. In the rare cases when you need to alter a quotation, be sure to use square brackets to indicate additions and ellipses to indicate omissions within the quoted passage. 4. Analyze the quotation in order to explain how it relates to the specific point of your paragraph and how it relates to the thesis of your paper. This step usually takes a few sentences. The key is to be specific in pointing out exactly what it is about the evidence that proves your point, and why it does so. For example, you might mention a particular word or phrase from the quoted passage and then explain the meaning of its connotations, of a figure of speech, or of an allusion. Even if these things seem obvious to you, your job here is to make them obvious to your readers in order to convince them of your interpretation. A few examples of how to do this fourth step: • Manfred shows his true nature when discussing his dead son, even going so far as to say he would be given "reason to rejoice" in a few years (Walpole 27). Walpole's use of the word rejoice expresses how little empathy Manfred has for his family. • When Theodore is about to be executed, the author writes, "The undaunted youth received the bitter sentence with a resignation that touched every heart but Manfred's" (Walpole 50). Walpole uses the word "undaunted” to prove to the reader that Theodore is courageous and does not fear death. The phrase "touched every heart but Manfred's" helps the reader appreciate the compassion that the bystanders had for Theodore despite Manfred's "bitter" decision. Walpole chooses his words carefully to create sympathy for Theodore and to make readers believe that Theodore's rise to the throne is just. The body of the essay should generally be structured according to P.I.E. P - Point: the argument you want to make (in other words, your major ideas, or this may be the topic sentence for a paragraph) I - Illustration: the example which supports/illustrates your point, a quote from a text or reference to some specific incident or observation. You must have an illustration for each major idea, though not necessarily for every single paragraph. A weak illustration will undermine your entire essay. E Explanation: brief discussion of how the illustration you've just used proves your point. Many beginning writers skip this step, but it is essential in creating a tight, convincing argument. Constantly imagine your audience looking over your shoulder at your illustrations and saying “So what does that prove?” ALWAYS answer this question with at least one sentence after each illustration or quote. Conclusion – This should sum up what you've just argued, and reinforce, not repeat, your thesis. Forbidden Phrases, and Things You Cannot Use as a Thesis: 1. "The author does a great job of....." Of course they do a great job. If they were lousy writers they would never have gotten published and you wouldn't be reading them in a college literature course. 2. "The author uses details to paint pictures of..." Yes, all good authors do this. This is an example of a sound observation that cannot be worked into a thesis. Who's going to argue with you about something so obvious? 3. "The author makes you see what they see/feel what they feel/experience what they experience..." Again, this is a common trait of nearly all good writing and filmmaking and therefore not something you need argue/prove in a thesis. Always remember that your audience has just finished reading the book you're writing about. Your job is to tell your audience something that isn't obvious, something they might not have noticed while reading the book themselves, something you have to PROVE to them through analysis and explanation, not just observation or restating in your own words what the author already said. Academic or scholarly articles are those that come from academic or scholarly journals (like the Journal of Modern Languages Association; the Journal of Gender Studies; Southwestern American Literature; Western American Literature; MELUS the Journal of Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the U.S.; American Literature, or American Indian Quarterly. They may also be scholarly articles that are published in a scholarly anthology--this is a book in which numerous academic articles on a certain subject have been collected and published together. If you find an article somewhere else, how can you tell if it is scholarly or not? 1.The author has a Ph.D. in the field and 2.The article is longer than what you would find in a popular magazine, generally more than 10 pages and 3.The article has a bibliography or works cited section, and all quotes and sources are cited—this one is absolutely essential! Some things to watch out for: 1. Just because the word "journal" is in the title does not guarantee the source is academic--The Ladies Home Journal for example, would not be an academic source. 2. Book or movie reviews are not articles, even if they are published in a scholarly peer-reviewed journal. They are too short to count as an article, and they don’t have a bibliography or works cited page. In other words, even though they are written by a scholar (usually) s/he has done no research for the review and is merely presenting an opinion. 3. WEB SITES ARE NOT SCHOLARLY SOURCES. There are a few exceptions to this. Jstor JSTOR The Scholarly Journal Archive is a sort of on-line library of scholarly journals. You can download any article from any journal they subscribe to for free from your eraider account. Some university departments and professors maintain websites containing the texts of academic articles. Also, some academic journals publish on-line versions. If a website does not meet these criteria, IT IS NOT CONSIDERED AN ACADEMIC SOURCE. 4. What if you type in your search term and get 142,867 hits? Or none at all? Try altering your terms. Think about other words to use: west, western, southwest, southwestern, Indian, Native American, American Indian, Hispanic, Mexican, Mexican-American, Chicano, Chicana, frontier, border, borderland, writer, author, etc. How should you organize your ideas? 1. Start with strongest one first (the one you have most support or best quotes for), then move to weaker ones. 2. Start with smallest or least important one and move to the climactic big one. This works well if you have a really controversial idea and you need to introduce people to it slowly. 3. Start broad, like a wide-angle shot with a camera, then slowly get more and more detailed, like moving in for a close-up. How do you know which ideas to choose or how to focus your essay? Try starting with an epigraph--this is a short quote from the text you'll be analyzing, or sometimes some other text that seems to say something really important or related to the piece you're writing about. An epigraph goes after the title of your essay, but before the first paragraph. It is tabbed in from both sides, and sometimes in italics. At the end of it, you don't need a full citation or page number, just the name of the author. An epigraph can help remind you what you found most interesting or compelling about a text, and therefore keep you focused on what you want your argument to be. It is also a cue to your audience about what they're going to be reading. Think of it as the opening scene in a movie. It sets the stage and the tone of what will follow.