AN ANALYSIS OF CONFLICT FOR THE A RESEARCH PAPER

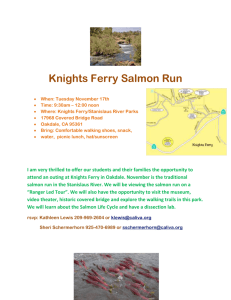

advertisement