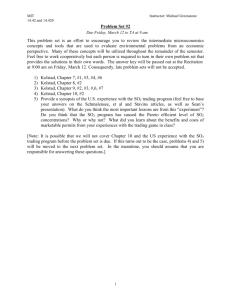

The Paparazzi Take a Look at a Living Legend: The SO Cap-and-Trade

advertisement