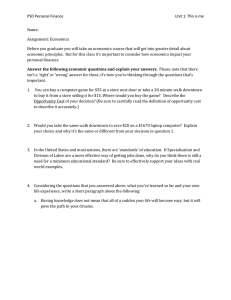

1/20/2016 ECON4260 Behavioral Economics 1

advertisement

1/20/2016 ECON4260 Behavioral Economics 1st lecture Introduction, Markets and Uncertainty Kjell Arne Brekke Practical Issues • Dates for seminar on web-page • Most paper available online – The rest in a compendium • For my topic: – – – – Relevant lecture indicated in the reading list. The fist handout will cover more than 1st lecture This lecture will be mostly PowerPoint In the three next I’ll mainly use the Department of Economics Three main topics • Decision theory (Lectures 1-4) – Decisions under uncertainty • Time preferences (Lectures 5-8) – 10$ today versus 11$ tomorrow – 10$ ten days from versus 11$ after 11 days • Justice / Non-selfish behavior (L 9-13) – Share 100 kroner with a recipient/responder – Dictators share – Responders reject unfair offers • But we will discuss experimental markets today. Department of Economics 1 1/20/2016 Time preferences / Self control • It is a good idea to read the papers before the lectures, and to allocate work evenly over the semester – Most students know – Some lack the self control to do it. • But then: – Who is the ’self’ if not the student? – If it is the student, who is the ’self’ controlling? • Theories of multiple selves Department of Economics Study pre-commitment technique • Suppose at the start of the semester you decide to – Solve all seminar exercises in advance – Read all relevant papers on the reading list before each lecture – Attend all lectures and seminars • But you know that you (maybe) will not follow through – And that you will regret as exams are approaching • Make a contract with another student – Attend at least 90% of lectures and seminars – have someone to sign. – Have written answers to 80% of all seminar problem (signed) • If the contract is not met – give 1000 kroner to an organization that you disagree strongly with. • Homo oeconomicus would not need this contract – Why do we need it? Department of Economics Social preferences • When you watch someone in pain and when you yourself is in pain, some of the same neurons light up in your brain. • Old wisdom: We share others pain, sorrow, happiness. – But may enjoy their pain if they have done us wrong • Is it then reasonable to assume my utility only depend on my own consumption? Department of Economics 2 1/20/2016 A class room experiment • If more than 30, sit together in pairs • About 1/3 will be sellers, and 2/3 buyers • Sellers has a cost 1 and buyers has value 4 – – – – If a seller sell at p, he/she earns p-1 twist The buyer earn 4-p twist in paid rounds Sellers can only sell 1 unit, and buyers only buy 1 unit. The price has to be an integer – Twists are non-divisible • Double auction – Sellers can announce a selling price • Any buyer can accept a standing offer – Buyers can announce a buying price • Any seller can accept standing offers – All prices can be changed until a deal is made Department of Economics Double auctions • Both sellers ask and byers bid • Findings generally consistent with theory • But there is an adjustment process toward equilibrium – – – – – Start away from equilibrium and move toward it. Jumps away again at the start of next period (sawtooth) Last movement in the period is toward equilibrium. Last action a concession. (e.g. seller lowering price.) More bids than aks (excess demand) -> increasing price Department of Economics Information • Note that you only know your own payoff • The equilibrium can only be computed if you knew everybody's payoff. • The market reveal this information • In some experiment the value of an item is unknown and depend on the state. – If two players know the state other not, then everybody learn the state within seconds. – You cannot make a profit from knowing that the state is high without making a bid, thus revealing that you know the state is good. Department of Economics 3 1/20/2016 Induced values • The payoff is controlled by experimenter. • You where told how much the item was worth/cost – No social construction of values – No fashion • Still, we do not have perfect control of the utility function. – Some players may prefer to leave the lab with 50 kroner less but a better conscience – This will in particular be the case in the experiments discussed in the last part of the course. Department of Economics Experiments in Economics • They are always paid. – With money – not Dumble • Deception is not allowed while deception is used in psychology – The Asch experiment. • Lab experiment with students dominates – But an increasing amount of field experiment. Department of Economics Back to decision theory How to make the optimal decision in theory • For each alternative action: – Make an assessment of the probability distribution of outcomes – Compute the expected utility associated with each such probability distribution – Choose the action that maximize expected utility • How do people make probability assessment? Department of Economics 4 1/20/2016 Fundamental law of statistics • If the event A is contained in B then Pr(A) ≤ Pr(B) • Example: An urn contains Red, Blue and Green balls. A ball is drawn at random Pr(Red OR Blue) ≥ Pr(Red) • Conjunctions: A&B is contained in B Pr(A&B) ≤ Pr(B) • Applies to all alternatives to probability, like Belief functions and non-additive measures Department of Economics Linda • “Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.” – – – – – Linda is a teacher in elementary school Linda is active in the feminist movement (F) Linda is a bank teller (T) Linda is an insurance sales person Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement (T&F) • Probability rank (1=most probable): – Naïve: T&F : 3,3; T : 4,4 – Sophisticated: T&F : 3,2; T : 4,3. • Conjunction rule implies – Rank T&F should be lower than T (Less probable) Department of Economics Bill • Bill is 34 years old. He is intelligent but unimaginative, compulsive, and generally lifeless. In school he was strong in mathematics but weak in social studies and humanities. – – – – – – – – Bill is a physician who play poker for a hobby Bill is an architect Bill is an accountant (A) Bill plays jazz for a hobby (J) [Rank 4.5] Bill surfs for a hobby Bill is a reporter Bill is an accountant who play jazz for a hobby (A & J) [Rank 2.5] Bill climbs mountains for a hobby. Department of Economics 5 1/20/2016 Indirect and Direct tests • Indirect versus direct – Are both A&B and A in same questionnaire? – Paper show that direct and indirect tests yield roughly the same result. • Transparent – Argument 1: Linda is more likely to be a bank teller than she is to be a feminist bank teller, because every feminist bank teller is a bank teller, but some bank tellers are not feminists and Linda could be one of them (35%) – Argument 2: Linda is more likely to be a feminist bank teller than she is likely to be a bank teller, because she resembles an active feminist more than she resembles a bank teller (65%) Department of Economics Sophistication • Graduate student social sciences at UCB and Stanford • Credit for several statistics courses – ”Only 36% committed the fallacy” – Likelihood rank T&F (3.5) < T (3.8) ”for the first time?” • But: – Report sophisticated in Table 1.1, no effect Department of Economics As a lottery • ”If you could win $10 by betting on an event, which of the following would you choose to bet on? (check one)” – ”Only” 56 % choose T&F over F Department of Economics 6 1/20/2016 Extensional versus intuitive • Extensional reasoning – Lists, inclusions, exclusions. Events – Formal statistics. • If A B , Pr(A) ≥ Pr (B) • Moreover: ( A & B) B • Intuitive reasoning – Not extensional – Heuristic • Availability • Representativity. Department of Economics Representative versus probable • ”It is more representative for a Hollywood actress to be divorced 4 times than to vote Democratic.” (65%) • But • ”Among Hollywood actresses there are more women who vote Democratic than women who are divorced 4 times.” (83%) Department of Economics Representative heuristic • While people know the difference between representative and probable they are often correlated • More probable that a Hollywood actress is divorced 4 times than a the probability that an average woman is divorced 4 times. • Thus representativity works as a heuristic for probability. Department of Economics 7 1/20/2016 Availability Heuristics • We assess the probability of an event by the ease with witch we can create a mental picture of it. – • Works good most of the time. Frequency of words – – – – A: _ _ _ _ ing (13.4%) B: _ _ _ _ _ n _ ( 4.7%) Now, ⊆ B and hence Pr(B)≥Pr(A) But ….ing words are easier to imagine Department of Economics Predicting Wimbledon. • Provided Bjørn Borg makes it to the final: – He had won 5 times in a row, and was perceived as very strong. • What is the probability that he will (1=most probable) – Lose the first set (2.7) – Lose the first set but win the match (2.2) • It was easier to make a mental image of Bjørn Borg winning at Wimbledon, than losing. Department of Economics We like small samples to be representative • • • Dice with 4 green (G) and two red (R) faces Rolled 20 times, and sequence recorded Bet on a sequence, and win $25 if it appear 1. RGRRR 2. GRGRRR 3. GRRRRR • 33% 65% 2% Now most subject avoid the fallacy with the transparent design Department of Economics 8 1/20/2016 More varieties • Doctors commit the conjunction fallacy in medical judgments • Adding reasons – NN had a heart attack – NN had a heart attack and is more than 55 years old • Watching TV affect our probability assessment of violent crimes, divorce and heroic doctors. (O’Guinn and Schrum) Department of Economics The critique from Gigerenser et.al • The Linda-case provide lots of irrelevant information • The word ’probability’ has many meanings – Only some corresponds to the meaning in mathematical statistics. • We are good at estimating probabilities – But only in concrete numbers – Not in abstract contingent probabilities. – Of 100 persons who fit the description of Linda. • How many are bank tellers? • How many are bank tellers and active in the femininist movement? – Now people get the numbers right Department of Economics More on Linda • In Kahenman and Tversky’s version even sophisticated subject violate basic probability • The concrete number framing removes the error • Shleifer (JEL 2012) in a review of Kahneman’s recent book (Thinking fast and slow.) – «This misses the point. Left to our own devices [no-one reframes to concrete numbers] we do not engage in such breakdowns» Department of Economics 9 1/20/2016 The base rate fallacy • Suppose HIV-test has the following quality – Non-infected have 99.9% probability of negative – Infected always test positive – 1 out of 1000 who are tested, are infected. • If Bill did a HIV-test and got a positive. What is the probability that Bill are in fact infected? – Write down your answer. Department of Economics Suppose we test 1001 persons • Statistically 1 will be infected and test positive • Of the 1000 remaining, 99,9% will test negative, and one will test positive. (on average) • If Bill did a HIV-test and got a positive. What is the probability that Bill is in fact infected? – Write down your answer. Department of Economics An advise • If you want to learn statistical theory, especially understand contingent probabilities and Bayesian updating: – Translate into concrete numbers • This will enhance – Your understanding when you study it, and – Your ability retain what you have learned 10 years from now. Department of Economics 10 1/20/2016 For the seminar A dice has four Green (G) faces and two Red (R) faces. The dice will be rolled 20 times, and the result (R or G) will be written down. This will produce a sequence of 20 letters. You can choose one of the three short sequences below: 1. RGRRR 2. GRGRRR 3. GRRRRR, Suppose that if your chosen sequence appears in the sequence of 20 letters, you would win 500 kroner. Which one of the sequences 1.-3. would you prefer? “ • • • Ask 4 students each, two sophisticated and two non-sophisticated. You may collaborate and attend lectures for first year students and students at intermediate/advanced courses in statistics at the math department. Send me the results prior to 3rd lecture. Department of Economics Expected utility • Preferences over lotteries • Notation – (x1,p1;…;xn,pn)= x1 with probability p1; … and xn with probability pn – Null outcomes not listed: • (x1,p1) means x1 with probability p1 and 0 with probability 1-p1 – (x) means x with certainty. Department of Economics Independence Axiom • If A ~ B, then (A,p;L,1-p) ~ (B,p; L,1-p) • Add continuity: if b(est) > x > w(orst) then there is a p(=u(x)) such that (b,p;w,1-p) ~ (x) • It follows that lotteries should be ranked according to Expected utility Max ∑ piu(xi) Department of Economics 11 1/20/2016 The idea of the proof Price L1 L2 L3 L4 100 ½ 0 p 1/3 45 0 1 0 1/3 0 ½ 0 1-p 1/3 • How to compare L1 & L2? • Continuity: – There is a p such that L1 ∼ 2 – Call this p for u(45) – Let u(0)=0 and u(100)=1 • If this p>1/2 we prefer L2 – Exp. Utility L1: ½u(100)+½u(0)=½ – EU L2: pu(100)+(1-p)u(0)=u(45) • EU for L4: – 1/3+1/3u(45) – Why do we need independence? Department of Economics Positive linear transforms • Note that if v(x)=au(x)+b, a>0 • Then Ev= ∑ piv(xi) = ∑ piau(xi)+∑ pib =a Eu + b • Maximizing Ev equivalent to maximizing Eu • Useful in the following – Can choose u(0)=0 – Use v(x)=u(x)+b, with b=-u(0) Department of Economics Prospect theory • Loss and gains – Value v(x-r) rather than utility u(x) where r is a reference point. • Decisions weights replace probabilities Max ∑ iv(xi-r) ( Replaces Max ∑ piu(xi) ) Department of Economics 12 1/20/2016 Evidence; Decision weights • Problem 3 – A: (4 000, 0.80) – N=95 [20] or B: (3 000) [80]* or D: (3 000, 0.25) [35] • Problem 4 – C: (4 000, 0.20) – N=95 [65]* • Violates expected utility – B better than A : u(3000) > 0.8 u(4000) – C better than D: 0.25u(3000) > 0.20 u(4000) • Perception is relative: – 100% is more different from 95% than 25% is from 20% Department of Economics Value function Reflection effect • Problem 3 – A: (4 000, 0.80) – N=95 [20] or B: (3 000) [80]* • Problem 3’ – A: (-4 000, 0.80) – N=95 [92]* or B: (-3 000) [8] • Ranking reverses with different sign (Table 1) • Concave (risk aversion) for gains and • Convex (risk lover) for losses Department of Economics The reference point • Problem 11: In addition to whatever you own, you have been given 1 000. You are now asked to choose between: – A: (1 000, 0.50) – N=95 [16] or B: (500) [84]* • Problem 12: In addition to whatever you own, you have been given 2 000. You are now asked to choose between: – A: (-1 000, 0.50) – N=95 [69]* or B: (-500) [31] • Both equivalent according to EU, but the initial instruction affect the reference point. Department of Economics 13 1/20/2016 Decision weights • Suggested by Allais (1953). • Originally a function of probability i = f(pi) • This formulation violates stochastic dominance and are difficult to generalize to lotteries with many outcomes (pi→0) • The standard is thus to use cumulative prospect theory Department of Economics Lotto (Think about this until next week) • 50% of the money that people spend on Lotto is paid out as winning prices • Stylized: – Spend 10 Kroner – Win 1 million kroner with probability 1 to 200 000 • Would a risk avers expected utility maximizer play Lotto? – Is Lotto participation a challenge to expected utility? • Can prospect theory explain why people participate in Lotto? Department of Economics 14