Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change Karen O’Brien

advertisement

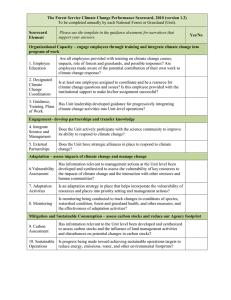

Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change Karen O’Brien Department of Sociology and Human Geography University of Oslo Karen.obrien@sgeo.uio.no Lecture Outline 1. Climate Change: A Brief Overview – 2. Climate Change Vulnerability – – 3. An ”Us and them” approach to climate equity Winners and losers Beyond the N-S Divide: Human Security – – 6. Adaptive capacity Sustainable adaptation The North-South Divide – – 5. Outcome vs. context Multiple stressors Climate Change Adaptation – – 4. Certainties and uncertainties Growing inequities, growing interconnections Addressing climate change vs. addressing human security Time to reframe the issue of climate change? – An environmental issue vs. a human security issue Key points • First, vulnerability to climate change is influenced by multiple processes of global change. • Second, changing economic and social policies strongly influence the capacity to cope with and adapt to climate change. • Third, vulnerabilities are linked through an increasingly connected global economy and society, such that actions and behaviors taken in one place have implications for other places. • Fourth, vulnerability to climate change is not limited to developing countries. 1. Climate Change: The Certainties • Atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases are increasing due to human activities • The climate is changing as a result. • There are already observed impacts of climate change. • The changes that we are seeing over a very short time scale are unprecedented in human history. Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, as is now evident from observations of increases in global average air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice, and rising global average sea level (IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, WGI, SPM, 2007) Observed and projected concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere 960 ppm 550 ppm CO2 (ppm) 280 ppm 200 ppm 5.8°C Temperatur (oC) 0°C • Today: Higher than in the past 650.000 år • 2100: -8°C Highest in millions (~20) of years 1.4°C The increase is mainly caused by burning of coal, oil and gas 850,000 650,000 650,000 år year 1850 2007 2100 Projected global warming 3 ºC: Irreversibe changes 2 ºC: EU target Requires > 50% cut in emissions by 2050 IPCC 2007 Projected global warming Has likely not been warmer during the past 3 mill years IPCC 2007 Projected global warming Has likely not been warmer during the past 3 mill years Mitigation Adaptation IPCC 2007 Today 2037 ‘57 Source: Helge Drange, Bjerknes Center 1. Climate Change – the uncertainties • We don’t know about the rate of future emissions. SRES scenarios have been developed following different story lines, but we don’t know which, if any, will be followed. • We don’t know exactly how climate variability will be influenced by climate change. • We don’t know about all of the feedbacks (biophysical and social) that may accelerate (or reduce) climate change. There is uncertainty in how climate change will interact with other processes of change. Changing variability and extreme events Source: Smit and Pilisofova 2003 Sea ice in the Arctic • Biophysical feedbacks: – Ice-albedo feedback – Permafrost-methane feedback • Social feedbacks – Northern Sea Route and global shipping – Oil and gas reserves in the Arctic 2. Climate Change Vulnerability • For some, vulnerability refers to the likelihood of injury, death, loss, disruption of livelihoods or other harms as the result of stressors or shocks resulting from climate change. Vulnerability is a measurable outcome of climate change. • For others, vulnerability is closely linked to context in which people experience shocks and stressors related to any type of change. Vulnerability is generated by social, economic, environmental, political, technological, and cultural conditions. Vulnerability • Outcome: Climate change will result in rainfall decreases that can lead to reduced maize yields, which can be considered a negative outcomes for farmers (i.e. farmers are vulnerable to climate change). • Contextual: Trade liberalization is changing the context for agriculture and farming in Mexico. Farmers are facing both import competition and climate variability and change. Their vulnerability to climate change is influenced by multiple processes. Source: O’Brien et al. 2007 Multiple processes of change • • • • • • Globalization Infectious diseases Violent conflicts Urbanization Technological change Etc. Implications • A small change in climate can have large consequences – it can push some people over the edge in terms of what they can cope with. • Dangerous climate change means different things to different people/groups/regions! 3. Climate Change Adaptation • Many people and societies are not welladapted to climate variability; • A changing climate means more variability and uncertainty; • Regardless of GHG reductions, we can expect some climate change in the coming decades. • Adaptation is a key response to climate change. Definition of Adaptation • Adaptation can be described as adjustments in practices, processes, or structures to take into account changing climate conditions, to moderate potential damages, or to benefit from opportunities associated with climate change (McCarthy et al., 2001). • Adaptation can occur in response to gradual changes, to changes in variability and extreme events, or to projected scenarios of future climate change. • Adaptations can be spontaneous or planned. Adaptive Capacity • A function of wealth, technology,information, skills, infrastructure, institutions, equity, empowerment, and the ability to spread risk. • Unevenly distributed – some will be able to adapt better than others. Sustainable Adaptation • The broader goals of most sustainability efforts are to foster economic and social practices that contribute to the maintenance of environmental quality, diversity of species and preservation of ecological functions for the benefit of both humans and other living things; • Combining aspects of both sustainability and adaptation, the notion of sustainable adaptation entails measures that reduce vulnerability and promote long-term resilience in a changing climate. The relationship between poverty and vulnerability • Vulnerability to climate change can often lead to poverty outcomes • Non-poor can be vulnerable • Not all poor are vulnerable, or vulnerable in the same ways Reducing vulnerability through adaptation • Reducing risk and exposure to risk • Increasing adaptive capacity • Decreasing underlying causes of vulnerability Questions to think about: • Does high adaptive capacity inevitably lead to adaptation? • Is one person/group/nation’s adaptation another’s vulnerability? • Is migration an adaptation, or a failure to adapt? 4. The North-South Divide • Most emissions have been produced by industrialized countries; • The most vulnerable to climate change are often those who have contributed least to it, and who have little voice in deciding what to do about it. • Climate change as an issue of equity, justice and fairness. Equity Issues in Mitigation and Adaptation • Responsibility, compensation, implications for future development, implications for future generations. • “The cardinal climate change inequity is … not the potentially unfair allocation of mitigation targets but the inevitably unfair distribution of climate impact burdens.” (Müller 2002) A Global Stalemate • Whose responsibility is it to mitigate climate change; who should pay for adaptation? If 80% emissions cuts are required by 2060, then how do we mobilize action? • How do individuals and communities respond to change, and is it possible to avoid the ageold tendency to wait until after a disaster has occurred to respond? ”Us versus them” mentality • Does the North-South divide perpetuate an ”us vs. them” attitude towards climate change? • Does it contribute to Northern complacency? • Does it contribute to Southern victimization? -- Reflects one type of power relations (national) but hides other types (class, gender, age) Winners and losers • Who wins from climate change? • Who loses? • Are these relative or absolute? Static or dynamic? At what spatial and temporal scales? • Who outcomes inevitable? • Who decides? 5. Human Security • • • • Freedom from fear, freedom from want (1945); Safety from chronic threats, protection from disruptions. Seven dimension of human security: personal, environmental, economic, political, community, health, and food security (UNDP 1994); ”The objective of human security is to safeguard the vital core of all human lives from critical pervasive threats, in a way that is consistent with long-term fulfillment (Human Security Commission, 2003); Human Security is achieved when and where individuals and communities have the options necessary to end, mitigate or adapt to threats to their human, environmental and social rights; have the capacity and freedom to exercise these options; and actively participate in pursuing these options (GECHS 1999). Human Security • Puts individuals and communities at the center of analysis, and focuses on how they can respond to change; • Has both internal and external dimensions. It is as much about psychology and personal development as it is about economic and social development; • It is about what people value and why, and how these shape priorities and actions. Two dimensions of human security • Equity dimension (fairness, justice, ethics) • Connectivity dimension (economic, social and political interests) Human security: The equity dimension • Recognizes deep social and economic inequalities; • Emphasizes the role of context; • Focuses on structures that create insecurities based on race, class, caste, gender, age, or simply place; • Draws attention to role of agents (power and politics) in producing or reducing human security; • Relational aspects: one individual’s security is often another’s insecurity. Human : the connectivity dimension • Takes a ”big picture” view of human security; • Sees humans as part of a larger ”global system”, where processes and outcomes are linked over space and time. 6. Time to reframe the issue of climate change? • How we frame climate change matters! • The dominant discourse has focused on climate change as an environmental problem. • This dictates the questions that are asked, the research that is done, and the policy responses that are adopted. • What if we reframe climate change as an issue of human security? Discourses • a “system of representation made up of rules of conduct, established texts and institutions which regulate what meanings can and cannot be produced.” (Foucault in Smith 1998) • “an area of language use expressing a particular standpoint and related to a certain set of institutions. Concerned with a limited range of objects, a discourse emphasizes some concepts at the expense of others.” (Peet and Watts 2001) • “the process through which social reality inevitably comes into being.” (Escobar 1996) Discourses on Climate Change • A discourse may speak to someone’s truth, but ignore or disregard another’s truth. • Discourses are about power relations; they are not neutral. • Whose truth counts? • Example: Climate change is a pollution problem vs. Climate change is a social problem. Climate change as a human security issue • Need to address the underlying factors that contribute to insecurity; • Responses to climate change that prioritize human security – is a normative and ethical approach needed? • ”The assumption that the environment is separate from both humanity and economic systems lies at the heart of the policy difficulties facing sustainable development and security thinking. The idea of environment as an independent variable—something that is beyond human control and that stresses human societies in ways that require a policy response—presents a problem for the environmental dimension of human security.” (Dalby 2002) “The world we have made as a result of the level of thinking we have done thus far creates problems we cannot solve at the same level of thinking at which we created them.” -- Albert Einstein Change the way that you look at things, and the things that you look at will change.