Subprime Lending: Neighborhood Patterns Over Time

advertisement

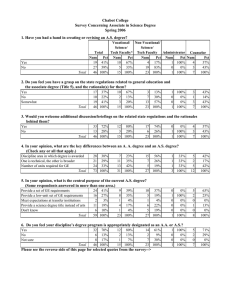

Subprime Lending: Neighborhood Patterns Over Time Jonathan Hershaff, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Susan Wachter, University of Pennsylvania Karl Russo, University of Pennsylvania For presentation to the conference of: Promises & Pitfalls Federal Reserve System’s Fourth Community Affairs Research Conference on April 7-9, 2005 Corresponding Author Susan M. Wachter Richard B. Worley Professor of Financial Management; Professor of Real Estate and Finance Wharton School University of Pennsylvania 3733 Spruce Street 430 Vance Hall Philadelphia, Pa 19104 215-898-6355 wachter@wharton.upenn.edu For comment only: do not cite without permission 1 Abstract Previous research has shown that subprime lending occurs disproportionately in markets with higher risk as well as larger shares of minority households. This paper extends the literature by identifying how subprime lending has changed over time, following subprime lending trends in seven cities across the US and their neighborhoods, defined by zip codes, and comparing outcomes in 1997 and 2002. We find major shifts in subprime lending patterns over this time period. In this period of overall growth, in many areas, and in two of the cities, subprime lending decreases. We identify factors associated with subprime lending trends and shifts in lending patterns over time. Growth in subprime lending is strongly associated with growth in Hispanic households and is also more likely to occur in neighborhoods with households who have low levels of educational achievement. Lower median income is less associated with subprime lending in 2002 than in 1997; risk measures and percentage share of African-American households, holding risk constant, are more strongly associated with subprime market share over time. 2 Subprime Lending: Neighborhood Patterns Over Time By Jonathan Hershaff Susan Wachter Karl Russo I. Introduction In this paper, we track changing patterns of subprime lending across neighborhoods in seven major cities in the US over a five-year period. Subprime lending increases substantially on average from 1997 to 2002, however growth is not uniform across neighborhoods. In specific areas, and in two of the cities, the number of subprime loans decreases over time. We identify factors associated with shifting neighborhood patterns of subprime lending, by estimating timeseries regressions of subprime growth. We also implement cross-section estimations of the 3 factors associated with subprime lending for 1997 and 2002 to determine whether these correlates change from 1997 to 2002. The substantial growth in subprime lending nationwide is shown in Table 1. Mortgage lending increases steadily from 1996 to 1999, decreases in 2000 due to the downturn in the economy, and then increases dramatically in the aftermath of the recession and the ensuing flurry of refinancing activity. Table 2 shows the monetary volume of this trend. After the decline in 2000, the growth trend resumes doubling of the number of subprime loans with an even greater increase in the dollar volume of lending through 2003. Despite the robust growth of subprime lending nationwide, there are persistent declines in subprime lending across and within some cities. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the changing patterns of lending for Philadelphia, which along with Baltimore, experiences a decline in the number of subprime loans from 1997 to 2002. The areas within Philadelphia with the largest declines appear to be low-income and high-risk neighborhoods, as defined by zip codes in the bottom quintile of income and in the top quintile of risk for each city, with risk measured by zipcode-level averages of credit scores and default rates. Tables 3 and 4 present findings on subprime growth by neighborhoods, segmented by risk and income measures. Absolute and/or relative declines in subprime lending occur in areas of low income, high credit risk and high default risk. Much of the literature on the spatial patterns of subprime lending finds a disproportionately large market share for subprime lending in low-income and heavily proportioned minority neighborhoods. Subprime, by definition, serves markets with greater risk, so that an explanation of these observed patterns may be found in the risk characteristics of neighborhoods. Nonetheless, these will be the markets with greater losses ex post; thus, with 4 “learning” over time, subprime lenders may adjust pricing or may lend less to neighborhoods with higher ex post measured risk. Similarly, it appears that subprime lenders are expanding more in relatively higher income areas, perhaps motivated by selecting borrowers with the ability to pay higher subprime lending rates. In this paper, we examine whether and how patterns of subprime lending are changing over this five-year period. Have subprime lenders withdrawn from or expanded less in markets with lower income and/or greater risk? We analyze the factors associated with differing growth rates in subprime lending across markets. We also separately estimate cross-section city-level regressions for 1997 and 2002 to test for whether there are changes in the factors associated with subprime market share, particularly focusing on whether there is a change in the role of risk and income measures over time. The degree to which subprime lending correlates with neighborhood economic and demographic characteristics is of interest because high subprime default rates are more likely to have adverse consequences for communities to the extent that subprime loans are concentrated in neighborhoods that are fundamentally more vulnerable to economic decline. Correlations of subprime lending with neighborhood demographic characteristics are also of interest because they may reflect “targeting” through more intensive marketing of subprime products. In Section II which follows, we review the literature on the spatial patterns of subprime lending. In Sections III and IV respectively, we review data sources and methodology. Empirical results are presented and discussed for the subprime change and city-level crosssection estimations in Section V. Section VI briefly concludes. II. Literature Review 5 The literature on neighborhood patterns of subprime lending examines the frequency of subprime borrowing relative to prime borrowing in residential mortgage markets in relation to both borrower and neighborhood characteristics. All such studies rely on data on the individual characteristics of mortgage loans and borrowers that are collected by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), in accordance with the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA). HMDA data do not separately identify subprime loans, so these studies rely on the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) list of lenders that specialize in the subprime market and use loans originated by these institutions as a proxy for subprime loans, while all other loans are treated as prime. Previous studies generally find significant concentrations of subprime lending among minority borrowers or within neighborhoods where minority households predominate. Bunce (2000) present evidence that on average nationwide, subprime loans are three times more frequent in low-income neighborhoods than in upper-income neighborhoods and five times more frequent in predominantly black neighborhoods than in predominantly white neighborhoods. Canner et al. (1999) find that subprime lending increases the number of loans to low- or moderate-income and minority households and to low- or moderate-income and predominantly minority neighborhoods. Moreover, Canner et al. show that increases in subprime lending go disproportionately to minority tracts and are responsible for more than one-third of the growth in overall lending to predominantly minority tracts between 1993 and 1998. Immergluck and Wiles (1999) also show subprime lending as a share of overall lending has been increasing in neighborhoods with high concentration of minorities. However, neither study controls for neighborhood characteristics such as risk. 6 Sheessele (2002) identifies the type of neighborhoods in the nation as a whole where borrowers are likely to rely on subprime loans for refinancing. This study finds that even after controlling for several neighborhood characteristics, the percentage of African-Americans is positively related to the share of subprime refinance. Pennington-Cross et al. (2000) provides evidence that the subprime market does not primarily originate mortgages to lower income borrowers; rather such lending primarily serves higher risk borrowers. In addition, this study finds that black and Asian borrowers have a higher probability of using the subprime market. Pennington-Cross (2002) indicates that subprime lending is most prevalent in locations with declining house prices. Calem, Gillen, Wachter (2004) include, together with other neighborhood variables, neighborhood credit risk measures. They find a correlation associating subprime lending with minority areas in multivariable regression analyses using 1997 HMDA data; when including risk variables, coefficients on percent minority drop in general by approximately onehalf. Calem, Hershaff, Wachter (2004) replicate this study for 2002, including additional cities, and find similar results. The National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC 2003) partially replicates the CGW study analyzing subprime lending in ten large metropolitan areas. As in CGW, measures of the credit-quality composition of neighborhood residents are included along with a number of neighborhood economic and demographic variables. The NCRC study finds that, in nine of the ten cities, the proportion of subprime refinance lending increases as the proportion of minorities in a neighborhood increased, all else equal. Apgar et al. (2004) extend this analysis to more MSAs, replicating the logistic analysis of CGW, although they do not include measures of the credit-quality composition of neighborhood residents. They find that the proportion of 7 minorities in a neighborhood is significant and negatively related to the market share of prime lenders. This paper extends the literature by focusing on shifting subprime lending patterns over time and explaining these patterns by including new risk information. Using data on neighborhood default rates we construct predicted default rates by zip code for the seven cities in the study to measure and control for property risk. As Calem and Wachter (1999) and Calem, Gillen and Wachter (2002) show, property and borrower risk are both important as contributors to the overall risk of mortgage lending. Borrower risk is important in delinquency and property risk, in default. III. Data We use five main sources of data for the analysis. For all sources, data are organized by zip code, and we construct risk variables by zip code as well. First, for individual characteristics of mortgage loans and borrowers in each city, we use HMDA data for the years 1997 and 2002. From these data, we derive several zip-code-level variables. Second, we use HUD’s list of lenders that specialize in the subprime market to identify each loan as being subprime or not. Throughout the empirical analyses, we use data for these lenders that are identified as subprime for refinance mortgage loans only. Third, we use 2000 Census data to construct tract demographic variables and neighborhood risk measures. Fourth, we use information on the distribution of credit ratings within tracts available from CRA Wiz®, a product of PCI Services in Boston that provides comprehensive, geography-based information. Finally, we obtain data on default activity by zip code from Anonymous Credit Information Company. Table 5 defines variables that we derive from these data and use in the empirical analysis. 8 From the 2000 Census, we obtain a number of tract-level economic and demographic variables for use in the analysis. These include the log of tract median family income (LN MED INCOME), the percent of individuals 25 years of age or older with a bachelor’s degree (PCT COLLEGE), and the proportion of occupied housing units that are renter-occupied (PCT RENT). Since economic conditions tend to be better in neighborhoods where residents have higher incomes or educational attainment, and since borrower financial sophistication tends to be directly related to educational attainment, we expect subprime borrowing to be inversely related to these variables. Since home ownership tends to be associated with less risk and higher levels of household wealth, we expect subprime borrowing to be directly related to percentage share of renter-occupied housing. Three measures of percent minority population: the percent of households headed by a person classified as African American, the percent headed by a person classified as Asian, and the percent headed by a person classified as Hispanic, (respectively PCT BLACK, PCT ASIAN, PCT HISPANIC) also are used. A proxy for the price of risk in real estate investment, the tract’s capitalization rate (CAP RATE), defined as a ratio of the tract’s annualized median rent divided by the median house value, also is constructed using 2000 Census data. A larger value for this measure is consistent with lower expected price appreciation or more uncertain future house prices and, hence, indicates increased risk. Hence, we expect this variable to be positively associated with the relative likelihood of a loan being subprime. Using CRA Wiz®, we calculate two measures of the credit-quality composition of neighborhood residents by census tract. These are the percent of adult individuals in a tract that have been classified as very high credit risk (PCT VHIGH RISK), based on their credit score, 9 and the percent with no credit rating (PCT NOINFO RISK). Both are expected to be positively associated with the relative likelihood of a loan being subprime. The tract variables are then aggregated to a Census-developed proxy for zip codes: zip code tabulation areas (ZCTAs). "ZCTAs are generalized area representations of U.S. Postal Service (USPS) ZIP Code service areas. Simply put, each one is built by aggregating the Census 2000 blocks, whose addresses use a given ZIP Code, into a ZCTA which gets that ZIP Code assigned as its ZCTA code. They represent the majority USPS five-digit ZIP Code found in a given area. For those areas where it is difficult to determine the prevailing five-digit ZIP Code, the higher-level three-digit ZIP Code is used for the ZCTA code (http://www.census.gov/geo/ZCTA/zcta.html).” Median family income, rent, and house value were weighted by the number of occupied housing units in the tract. Percent with at least a bachelor’s degree was weighted by the tract population over 25 years of age. A number of borrower characteristics from HMDA data are used as independent variables in the borrower-level logistic regressions. Specifically, we employ dummy variables on the borrower’s racial and gender characteristics (BLACK, HISPANIC, ASIAN, FEMALE) and also include the log of borrower income (LN_INCOME). The analysis below also includes the actual or a predicted probability that a loan is more than 90 days delinquent, hereafter referred to somewhat loosely as the (predicted) default rate (DEFAULT and PRED DEF, respectively) as another measure of risk. Because there is some concern over endogeneity, the predicted variable is constructed using a two-stage estimation procedure.1 In the first stage, we use the Anonymous Credit Information Company data to 1 Initially, a simple prediction of foreclosure rate was employed which included all of the loan-level and zip-level variables and additional interactions for collateral class and city dummies. However, we prefer the two-stage estimator. While there is little or no change in the performance of the regressions on the loan-level variables, we see some improvement in signs and/or significance of the other risk variables, particularly credit risk.. 10 estimate the foreclosure rate as a function of the loan type and age category as well as loan collateral class. We regress the residual from this first stage on loan-to-value categories, the demographic and credit-risk variables described above, and city dummy variables. The predicted default rates from this equation enter the city-level logistic regressions for subprime lending. These regressions are run without the default rate and with the actual default rate for a check on robustness. Table 6 presents sample mean values. The table shows that cap rates are similar across cities over time except that Philadelphia and Baltimore have high cap rates, consistent with the fact that they are losing population. Also, the median family income values point to Philadelphia and Baltimore as relatively low income and to Dallas and Atlanta as high income cities. Minority percentages vary as expected. The percentage of college graduates ranges from a low in Philadelphia of 18% (22% in 2002) to a high in Atlanta of 40% (44% in 2002), with the average of the sample cities at 27% (30% in 2002). Home-ownership rates vary across the cities from a low of 42% (45% in 2002) in New York to a high of 63% (62% in 2002) in Philadelphia. The average home-ownership rate for the cities considered is 53% (same in 2002). The increasing trend in these variables does not reflect changes in the underlying demography of neighborhoods, since these data all derive from the 2000 census; rather they suggest that the neighborhood composition of subprime lending is shifting over time towards neighborhoods with higher levels of social and economic capital. The borrower-income-level variable shows that the lowest income level is $43,000 ($66,000 in 2002) in Philadelphia and that Dallas has the highest income level of $94,000 ($98,000 in 2002). The other borrower characteristics vary across cities in expected ways. 11 As can be seen, the percentage of subprime loans varies a great deal across cities. For all cities, subprime lending as a percent of total lending declines over time from 33% to 14%. This is in part because of the surge of refinance loans in 2002 during a period of very low interest rates which spurred refinancing activity. This is evidenced by the more than three-fold aggregate increase in the number of subprime loans and the nearly four-fold increase in the number of prime loans. The pattern of the increase in subprime lending varies across cities, with some areas and cities showing declines. In the following section, we turn to explanations of these shifts. IV. Methodology We begin by looking at simple cross tabulations of subprime lending activity over time, focusing on the core central cities within each MSA. This represents the unconditional pattern of subprime lending activity over the period. The next step involves several regressions of the rate of change in the number of subprime loans from 1997 to 2002 at the zip code level. We first examine simple pooled regressions of rate of change of subprime lending against city dummies and dummy variables for whether the zip code is in the highest credit or foreclosure risk or lowest income quintile for each. This is undertaken to confirm the relationships evident in the cross tabulations. Other zip-level variables are then added to the regressions to see whether these relationships are robust to inclusion of other covariates. Finally, the analysis returns to loan level regressions by city of whether a loan is subprime on all of the zip-code-level and borrower-level variables listed in Table 5. We include as controls individual characteristics of borrowers, but because we lack individual credit-score data, we focus on the results for associations of zip-codelevel neighborhood factors with subprime market share. 12 V. Empirical Results Results shown in Table 3 and 4, calculated from the simple cross tabulations, indicate that subprime lending expanded less or contracted more than lending overall between 1997 and 2002. Both of these effects are robust across all cities and all risk areas with the exception of overall lending and overall subprime lending in Dallas, where relatively small base numbers in 1997 somewhat distort the percentage changes. The mean rate of growth at the zip-code level is 193% for all cities, consistent with the observed expansion of subprime lending. Results for Time Series Estimation Univariate regression results, with subprime lending as the dependent variable, shown in Table 7, are consistent with the cross tabulations and confirm the pattern of slower growth of subprime lending in areas of high credit risk (column 1), high default risk (column 3), or lower area income level (column 5) as defined by zip codes in the top quintile of respective risk or lowest median family income quintile for each city. The expanded models: 2, 4, and 6, shown in Table 7, include all other variables, with high credit risk, high default risk, and low income quintiles entering respectively. Model 7 includes all variables, while model 8 excludes the default measures to check for robustness. In these expanded models, high-risk areas are no longer significant as detractors to growth2. Consistently significant variables include percent Hispanic, percent with bachelor degree, and median family income. Subprime loan growth, is higher in areas with more Hispanic households, lower educational outcomes, and higher median income. 2 The observed effect of neighborhoods being in the lowest quintile of median family income also dissipates but the continuous income variable is significant. 13 The observed effect of being high risk, in the cross tabulations and in the single-variate estimation, is insignificant when controlling for other zip-code level characteristics. Percent Hispanic, percent college educated, and log of median family income have strong effects on subprime growth rates. An increase in the Hispanic population from 10% to 20% is associated with an approximately 70% higher subprime growth rate in a zip code. Subprime lending growth is also lower in highly educated areas. A one-standard-deviation increase (20-percentage points) in the percentage of individuals with a bachelor’s degree is associated with a nearly 200percentage-point reduction in the growth rate of subprime lending While seemingly expanding less in risky markets, it appears that it is low income rather than risk per se that is discouraging growth. The coefficient on LN MED INCOME implies that a a zip code with a 10% higher median family income experiences a 50% higher growth rate in subprime lending, all else equal.3 Cross-Section Estimation Results Tables 8 and 9 show results from loan-level regressions for whether a loan is likely to be subprime or not for each city for 1997 and 2002, respectively. Using the results shown in Tables 8 and 9, we compare the coefficients for the 1997 and the 2002 regressions to determine for each variable how many cities have coefficients that are significant and of the correct sign. In 1997, focusing on neighborhood variables, we find that, all else equal, areas with lower family income have a higher percentage of subprime loans. This is the only consistently significant neighborhood variable in 1997. The results from 2002 show some interesting comparisons. In that year, CAP RATE is much more consistently positive and significant as is PCT NOINFO RISK. This implies a 3 Median family income for the sample ranges from $11,250 to $171,750 with a mean of $44,800. 14 stronger association of risk variables with subprime lending over time. PCT BLACK also more consistently has positive and significant coefficients and PCT COLLEGE more consistently has negative and significant coefficients. In general for 2002, risk variables have the expected positive signs, indicating riskier areas attract more subprime lending. In addition, percent college is now inversely related to share of subprime lending. It is noteworthy, however, that median income is no longer consistently associated negatively with subprime lending as it was in 1997. In 2002, coefficients on median income are negative and significant in three rather than four markets with size of coefficients in these markets declining by more than one-half. One market, Dallas, shows a positive and significant coefficient on median income in 2002. Tables 10 and 11 leave out the predicted default rate while Tables 12 and 13 use the actual default rate instead. These alternative specifications reveal a broadly consistent story. The risk variables, however measured, become more strongly associated with subprime lending over time. This is evidenced by more positive and significant coefficients in 2002 and/or fewer negative and significant coefficients relative to 1997. PCT COLLEGE also becomes more strongly inversely associated with subprime lending over time. It has a negative sign in all but one city in Tables 9, 11, and 13 compared to mixed results in 1997 Tables 8, 10, and 12. Median income shows the reverse movement of education. It is negative and significant almost universally in 1997 and has mixed results or insignificance in 2002. Discussion of Results When determinants of the rate of growth of subprime lending are analyzed in a singlevariate regression, both default risk and credit risk, defined as zip codes in the top risk quintile, are detractors to growth. However, in a multi-variant regression with other variables included, both risk measures become insignificant. Low neighborhood income is a detractor to growth in a 15 single-variant regression and remains a significant detractor (measured as a continuous variable) in the multi-variate regression. In the city-level regressions, the coefficients of low area income shift from uniformly positive and significant in the 1997 regressions to low levels of significance in 2002. This suggests that low-income areas, all else equal, are less attractive to subprime lending. On the other hand, neighborhood risk measures become more significant in the 2002 regressions, with the expected positive coefficients. This result contradicts the apparent negative effect of high risk on subprime share in the cross tabulations which do not control for any covariates, but is not inconsistent with the insignificant coefficient of these variables in the multi-variate change regressions. In the city-level regressions, coefficients on racial composition of areas increase in their significance over time. The educational variable also becomes more consistently significant in 2002, with the expected negative coefficients, which again conforms to the apparent role of this variable in explaining growth in subprime lending over time, with areas with low levels of educational attainment, all else equal, even more attractive to subprime lending in 2002 than earlier. VI. Conclusion Subprime lending has grown significantly since 1997, particularly in areas of high Hispanic concentration and in areas with lower levels of household educational achievement. Subprime lending has grown less in low-income areas than elsewhere. In city-level regressions for 1997 and 2002, controlling for demographic variables, subprime lenders are more likely to be active in riskier areas (as defined by credit risk) in 2002 than in 1997. We also find that minority status -- in particular, percentage of African-American households -- continues to be 16 strongly associated with subprime lending in 2002, holding other variables constant. Consistent with rate-of-change results, low income is less related to subprime dominance in 2002 than in 1997. Finally, we find that lack of education, holding other variables constant, is a consistently significant factor in explaining the market share of subprime lending in 2002, as it is in explaining the growth of subprime lending over time. These results are preliminary; additional research for an expanded number of cities, incorporating expanded measures of risk is in process. 17 Bibliography Apgar , William Allegra Calder, and Gary Fauth “Industry Structure Perpetuates Dual Market” presented at the Federal Reserve System’s Community Affairs Research Conference, April 7, Washington D.C. Barakova, Irina, Raphael W. Bostic, Paul S. Calem, Susan M. Wachter. “Does Credit Quality Matter for Homeownership?” Journal of Housing Economics, 2004. Bunce. (2000). Curbing Predatory Home Mortgage Lending. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Working Paper Series. Calem, Paul S. (1996). “Mortgage Credit Availability in Low- and Moderate-Income Minority Neighborhoods: Are Information Externalities Critical?” The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 13(1): 71-89. Calem, Paul S. (1996). “Patterns of Residential Mortgage Activity in Philadelphia’s Low- And Moderate-Income Neighborhoods.” Mortgage Lending, Racial Discrimination, and Federal Policy, editors John Goering and Ron Wienk. Washington D.C., The Urban Institute Press, 671676. Calem, Paul S., and Susan Wachter. (1999). “Community Reinvestment and Credit Risk: Evidence from an Affordable Home Loan Program.” Real Estate Economics 27, pp.105-134. Calem, Paul S., Jonathan E. Hershaff, Susan M. Wachter. “Neighborhood Patterns of Subprime Lending: Evidence from Disparate Cities.” Housing Policy Debate. Vol. 15, No. 3. 2004. Calem, Paul S., Kevin Gillen, Susan M. Wachter. “The Neighborhood Distribution of Subprime Mortgage Lending.” Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics. Vol. 29, No. 4. 2004. Canner, Glenn B. and Elizabeth Laderman (1999). “The Role of Specialized Lenders in Extending Mortgages to Lower-Income and Minority Homebuyers.” Federal Reserve Bulletin, November. Engel, Kathleen C., and Patricia A. McCoy. “Predatory Lending: What Does Wall Street Have to Do with It?” Housing Policy Debate. Vol. 15, No. 3. 2004. Engel, Kathleen C., and Patricia A. McCoy. “Predatory Lending and Community Development at Loggerheads” Housing Policy Debate Federal Reserve Bank Conference, December 6, 2004 Immergluck, Daniel and Marti Wiles. Two Steps Back: The Dual Mortgage Market, Predatory Lending, and the Undoing of Community Development. Chicago, IL. November 1999. Joint Center for Housing Studies. (2004). Credit, Capital and Communities: The Implications of the Changing Mortgage Banking Industry for Community Based Organizations.” Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. 18 Ling, David C. and Susan M. Wachter. “Information Externalities and Home Mortgage Underwriting,” Journal of Urban Economics 44(3): 317-332. National Community Reinvestment Coalition. (2003), “The Broken Credit System: Discrimination and Unequal Access to Affordable Loans by Race and Age: Subprime Lending in Ten Large Metropolitan Areas,” Washington, D.C.: National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Pennington-Cross, Anthony. (2002). “Subprime Lending in the Primary and Secondary Markets.” Journal of Housing Research 13(1): 31-50. Pennington-Cross, Anthony and Joseph Nichols. (2000). “Credit History and the FHA Conventional Choice.” Real Estate Economics 28(2): 307-336. Pennington-Cross, Anthony, Anthony Yezer and Joseph Nichols. (2000). “Credit Risk and Mortgage Lending: Who Uses Subprime and Why?” Research Institute for Housing America, Working Paper No. 00-03. Scheessele, Randall M. (1998). “1998 HMDA Highlights.” Housing Finance Working Paper Series, HF-009. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. July. 19 Table 3 - Percent Rate of Change in Subprime Lending Activity Atlanta Baltimore Chicago Dallas Los Angeles New York Philadelphia 188.7 52.0 172.9 860.6 262.7 296.0 78.2 10.0 -53.8 8.3 900.4 64.9 100.2 -27.0 Number of Loans in High Credit Risk Areas 78.4 -30.0 16.5 663.8 154.9 158.4 -9.7 Number of Subprime Loans in High Credit Risk Areas 3.8 -71.5 -21.7 608.8 46.1 52.0 -51.3 126.0 5.3 19.5 684.2 143.1 177.3 -0.3 2.9 -68.6 -25.5 678.3 29.6 58.4 -52.5 145.0 -21.4 215.9 886.2 166.3 129.4 -23.2 2.7 -74.1 14.9 735.4 25.6 26.7 -60.9 Total Number of Loans Number of Subprime Loans Number of Loans in High Default Areas Number of Subprime Loans in High Default Areas Number of Loans in Low Income Areas Number of Subprime Loans in Low Income Areas Table 4 - Subprime Lending Activity Total Number of Loans Number of Subprime Loans Number of Loans in High Risk Areas Number of Subprime Loans in High Risk Areas Number of Loans in High Default Areas Number of Subprime Loans in High Default Areas Atlanta 1997 2002 Baltimore 1997 2002 Chicago 1997 2002 Dallas 1997 2002 Los Angeles 1997 2002 3,357 9,693 4,219 6,413 23,289 1,312 1,443 2,374 1,097 551 983 891 373 387 912 551 New York 1997 2002 Philadelphia 1997 2002 63,548 1,634 15,696 7,835 28,418 13,848 54,841 9,377 16,711 8,314 9,006 257 2,571 2,771 4,568 5,016 10,040 4,231 3,089 624 6,528 7,605 160 1,222 2,572 6,557 3,494 9,028 1,972 1,780 659 188 3,595 2,815 91 645 1,459 2,132 2,277 3,462 1,333 649 2,061 852 897 6,311 7,540 203 1,592 2,085 5,069 4,238 11,752 1,962 1,957 567 564 177 3,508 2,614 106 825 1,190 1,542 2,628 4,163 1,228 583 Table 5 – Variable Definitions Zipcode-level Variable Definitions Variable Definition PCT SUB Subprime as a Pct. of Loans Originated in the Zipcode PCT VHIGH RISK Pct. of Zipcode Population Very High Risk PCT NOINFO RISK Pct. of Zipcode Population With No Credit History PCT BLACK PCT HISP PCT ASIAN PCT COLLEGE Pct. of Zipcode Homeowners Black Pct. of Zipcode Homeowners Hispanic Pct. of Zipcode Homeowners Asian Pct. of Zipcode Pop. 25+ Years of Age with a Bachelor’s Degree PRED DEF Predicted Default Rate CAP RATE Median Rent / Median House Value LN MED INCOME DEF Log of Zipcode Median Income Default Rate Loan-level Variable Definitions Variable Definition SUB PRIME Dummy if Loan is Subprime BLACK Dummy if Borrower is Black HISPANIC ASIAN LN INCOME MISSING Dummy if Borrower is Hispanic Dummy if Borrower is Asian Log of Borrower Income Missing Information Table 6: Summary Statistics: Sample Mean Values Atlanta Variable 1997 Baltimore 2002 1997 2002 Chicago 1997 Dallas 2002 1997 Los Angeles 2002 1997 2002 New York 1997 2002 Philadelphia Whole Sample 1997 1997 2002 2002 ZIP-code-level variables CAP RATE Median Family Income 0.05 0.05 0.08 0.08 0.06 0.05 0.07 0.07 0.04 65,551 69,293 45,359 52,654 54,274 61,792 68,149 66,212 59,002 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.11 0.09 0.06 0.05 57,323 57,166 60,844 41,987 47,416 55,018 59,831 PCT ASIAN 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.03 0.05 0.04 0.04 0.09 0.10 0.08 0.09 0.04 0.04 0.05 0.07 PCT BLACK 0.52 0.46 0.55 0.40 0.33 0.19 0.13 0.12 0.12 0.10 0.29 0.24 0.45 0.30 0.30 0.18 PCT HISPANIC 0.05 0.05 0.02 0.03 0.21 0.21 0.19 0.21 0.33 0.35 0.18 0.18 0.06 0.05 0.20 0.23 PCT VHIGH RISK 0.18 0.17 0.18 0.18 0.17 0.17 0.18 0.18 0.18 0.18 0.18 0.17 0.18 0.17 0.18 0.17 PCT NOINFO RISK 0.18 0.17 0.18 0.17 0.18 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.16 0.16 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.17 PCT COLLEGE 0.40 0.44 0.22 0.29 0.25 0.32 0.37 0.36 0.30 0.29 0.27 0.29 0.18 0.22 0.27 0.30 PCT RENTAL 0.51 0.52 0.43 0.42 0.45 0.43 0.41 0.41 0.50 0.48 0.58 0.55 0.37 0.38 0.47 0.47 87,539 76,789 90,520 42,671 66,052 65,389 85,770 Borrower-level variables INCOME 68,287 92,481 48,423 77,435 59,902 80,402 93,825 97,944 75,302 ASIAN 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.03 0.05 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.05 0.06 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.05 BLACK 0.34 0.21 0.40 0.15 0.24 0.11 0.06 0.05 0.11 0.05 0.15 0.14 0.27 0.11 0.21 0.09 HISPANIC 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.12 0.15 0.05 0.10 0.13 0.18 0.05 0.07 0.02 0.02 0.09 0.13 MISSING 0.17 0.22 0.22 0.28 0.14 0.13 0.10 0.18 0.16 0.24 0.29 0.31 0.29 0.35 0.19 0.22 SINGLE 0.67 0.73 0.63 0.66 0.49 0.52 0.43 0.51 0.49 0.56 0.56 0.63 0.59 0.64 0.52 0.56 SINGLE FEMALE 0.28 0.28 0.28 0.25 0.21 0.20 0.15 0.16 0.22 0.20 0.18 0.21 0.27 0.22 0.22 0.20 SINGLE MALE 0.39 0.45 0.35 0.41 0.28 0.32 0.28 0.35 0.26 0.35 0.38 0.41 0.32 0.42 0.30 0.36 SUB PRIME 0.39 0.15 0.52 0.15 0.32 0.12 0.13 0.14 0.27 0.13 0.36 0.18 0.45 0.19 0.33 0.14 3,403 9,920 4,816 Number of Loans 8,474 31,536 95,613 3,293 32,419 20,925 110,158 14,076 55,871 9,418 16,732 87,467 329,187 Table 7 Regression Results Percent Change in Number of Subprime Loans Central City Zip Codes 1997-2002 Intercept 1 11.45 2 -48.01 3 11.31 4 -47.13 5 11.39 6 -44.23 P-value 0.00 0.05 0.00 0.06 0.00 0.08 HIRISK -1.42 P-value 0.02 0.08 0.09 -0.53 -0.44 -0.51 0.56 0.65 0.58 HIDefault P-value -0.86 -0.16 -0.08 0.15 0.83 0.92 LOWINC P-value DEFAULT 7 8 -45.45 -43.07 -1.46 -0.46 -0.36 -0.31 0.01 0.62 0.71 0.74 -2.81 -2.49 -2.90 -2.53 0.50 0.61 0.49 0.60 14.77 8.27 8.34 13.66 12.36 0.66 0.79 0.79 0.69 0.71 -24.54 -27.32 -21.75 P-value 0.41 0.36 0.49 0.53 0.59 PCT BLACK 0.82 0.83 0.66 0.74 0.47 P-value 0.67 0.67 0.74 0.71 0.80 PCT ASIAN 3.58 3.68 3.54 3.44 4.04 P-value 0.30 0.29 0.31 0.32 0.24 PCT HISPANIC 7.18 7.31 7.24 7.15 6.99 P-value 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 -9.37 -9.57 -9.02 -8.91 -8.25 P-value 0.03 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06 PCT RENTALS 2.30 2.35 2.28 2.23 1.66 P-value 0.35 0.34 0.36 0.37 0.50 -0.16 -0.22 -0.09 -0.03 0.08 0.97 0.96 0.98 1.00 0.99 5.62 0.01 Yes 5.69 0.01 Yes 5.33 0.02 Yes 5.33 0.02 Yes 5.06 0.02 Yes 0.39 387 0.39 387 0.38 392 P-value PCT VHIGH RISK P-value PCT NOINFO RISK PCT COLLEGE CAP RATE P-value LN MED INCOME P-value City Dummies? R-squared N Yes 0.32 401 0.39 387 Yes 0.32 401 0.39 387 Yes 0.32 401 -20.34 -16.76 Table 8 - Loan-Level Regression Results for Refinance Loans 1997 Variable INTERCEPT INTERCEPT ASIAN ASIAN BLACK BLACK HISPANIC HISPANIC LN INCOME LN INCOME MISSING MISSING CAP RATE CAP RATE LN MED INCOME LN MED INCOME PCT RENT PCT RENT PCT COLLEGE PCT COLLEGE PCT ASIAN PCT ASIAN PCT BLACK PCT BLACK PCT HISPANIC PCT HISPANIC Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 1997 Baltimore 1997 Chicago 1997 Dallas 1997 Los Angeles 1997 New York City 1997 Philadelphia 1997 Whole Sample 1997 12.58 0.13 -1.74 0.10 0.45 0.00 -1.98 0.06 -0.84 0.00 1.45 0.00 0.66 0.93 -0.26 0.57 -0.90 0.46 -1.07 0.67 13.15 0.00 0.38 0.88 2.36 0.42 31.45 0.00 -0.24 0.61 1.00 0.00 1.07 0.01 -0.73 0.00 1.57 0.00 -4.27 0.31 -2.87 0.00 -0.73 0.41 1.52 0.18 5.63 0.14 0.49 0.66 -8.15 0.01 7.77 0.00 -0.13 0.21 1.02 0.00 -0.11 0.04 -0.52 0.00 1.22 0.00 0.15 0.83 -0.74 0.00 -0.30 0.35 0.15 0.75 0.28 0.55 1.92 0.00 0.36 0.46 -5.55 0.58 -0.57 0.29 0.46 0.04 -0.28 0.30 -0.65 0.00 1.04 0.00 3.12 0.41 0.58 0.38 0.38 0.72 -2.10 0.15 -4.78 0.06 1.16 0.57 0.36 0.82 7.55 0.01 -0.39 0.00 0.74 0.00 0.06 0.29 -0.26 0.00 1.48 0.00 -4.28 0.12 -1.17 0.00 -0.70 0.04 1.34 0.03 -0.54 0.11 1.52 0.01 -0.31 0.54 10.79 0.00 -1.12 0.00 0.48 0.00 0.00 0.98 -0.97 0.00 1.65 0.00 -4.89 0.02 -0.72 0.01 -1.24 0.00 -1.48 0.03 0.74 0.04 0.14 0.80 1.02 0.09 8.24 0.09 -0.91 0.00 0.87 0.00 0.03 0.85 -0.82 0.00 1.46 0.00 0.76 0.69 -0.87 0.08 -0.58 0.27 2.29 0.04 1.74 0.05 1.12 0.15 -0.02 0.99 10.17 0.00 -0.47 0.00 0.83 0.00 -0.05 0.16 -0.60 0.00 1.44 0.00 -1.36 0.01 -0.75 0.00 -0.92 0.00 -0.07 0.75 0.16 0.37 0.68 0.01 1.05 0.00 Variable PRED PCT DEFAULT PRED PCT DEFAULT PCT VHIGH RISK PCT VHIGH RISK PCT NOINFO RISK PCT NOINFO RISK SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE MALE SINGLE MALE Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 1997 Baltimore 1997 Chicago 1997 Dallas 1997 Los Angeles 1997 New York City 1997 Philadelphia 1997 Whole Sample 1997 0.35 0.50 -36.72 0.05 -7.06 0.81 -0.12 0.28 -0.03 0.81 -0.17 0.40 8.48 0.51 8.27 0.56 -0.30 0.00 -0.32 0.00 -0.14 0.22 -2.29 0.54 6.38 0.29 0.11 0.00 0.16 0.00 0.13 0.70 4.06 0.80 -5.12 0.78 0.34 0.05 0.61 0.00 -0.16 0.13 7.13 0.22 19.91 0.00 0.11 0.01 0.03 0.43 0.11 0.31 5.05 0.39 -0.59 0.92 -0.21 0.00 0.02 0.72 0.00 1.00 4.54 0.55 7.54 0.43 -0.18 0.01 0.29 0.00 0.07 0.12 -3.28 0.11 -2.37 0.36 0.00 0.86 0.10 0.00 Table 9 - Loan-Level Regression Results for Refinance Loans 2002 Variable INTERCEPT INTERCEPT ASIAN ASIAN BLACK BLACK HISPANIC HISPANIC LN INCOME LN INCOME MISSING MISSING CAP RATE CAP RATE LN MED INCOME LN MED INCOME PCT RENT PCT RENT PCT COLLEGE PCT COLLEGE PCT ASIAN PCT ASIAN PCT BLACK PCT BLACK PCT HISPANIC PCT HISPANIC Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 2002 Baltimore 2002 Chicago 2002 Dallas 2002 Los Angeles 2002 New York City 2002 Philadelphia 2002 Whole Sample 2002 -14.08 0.03 -0.39 0.41 1.07 0.00 0.46 0.16 -0.65 0.00 1.23 0.00 10.04 0.05 0.18 0.58 0.53 0.55 1.03 0.57 6.00 0.05 3.94 0.04 -1.23 0.56 -0.40 0.95 0.21 0.64 0.66 0.00 0.80 0.02 -0.78 0.00 1.29 0.00 5.15 0.26 -0.12 0.85 -0.88 0.32 -0.77 0.48 4.32 0.27 1.02 0.33 -2.09 0.43 -0.73 0.68 0.03 0.72 1.35 0.00 0.74 0.00 -0.44 0.00 1.12 0.00 1.12 0.02 -0.29 0.04 -0.04 0.87 -0.93 0.01 -0.42 0.23 2.28 0.00 0.05 0.89 -1.89 0.53 -0.60 0.00 1.09 0.00 -0.29 0.00 -0.65 0.00 0.98 0.00 4.50 0.00 0.78 0.00 -0.71 0.03 -4.21 0.00 1.45 0.07 -0.19 0.77 2.09 0.00 -1.27 0.43 0.12 0.00 0.88 0.00 0.45 0.00 -0.05 0.01 0.19 0.00 8.39 0.00 -0.45 0.00 -0.06 0.75 -0.75 0.03 0.04 0.83 1.28 0.00 -0.35 0.20 1.67 0.36 -0.48 0.00 0.60 0.00 0.53 0.00 -0.30 0.00 0.88 0.00 -4.39 0.00 -0.35 0.02 -0.54 0.01 -3.47 0.00 -0.43 0.03 0.95 0.00 -0.23 0.52 -2.01 0.63 -0.33 0.07 0.38 0.00 -0.23 0.15 -0.57 0.00 0.47 0.00 3.41 0.06 0.19 0.64 -0.54 0.24 -0.45 0.60 0.14 0.87 0.69 0.26 0.24 0.76 -1.79 0.01 0.02 0.58 0.88 0.00 0.48 0.00 -0.35 0.00 0.70 0.00 0.32 0.25 -0.03 0.57 -0.22 0.02 -2.24 0.00 -0.08 0.45 0.95 0.00 0.23 0.10 Variable PRED PCT DEFAULT PRED PCT DEFAULT PCT VHIGH RISK PCT VHIGH RISK PCT NOINFO RISK PCT NOINFO RISK SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE MALE SINGLE MALE Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 2002 Baltimore 2002 Chicago 2002 Dallas 2002 Los Angeles 2002 New York City 2002 Philadelphia 2002 Whole Sample 2002 -0.52 0.16 13.57 0.34 41.83 0.05 -0.06 0.55 0.12 0.17 -0.11 0.55 22.94 0.09 -6.72 0.63 0.00 0.97 0.20 0.03 -0.20 0.02 3.96 0.17 13.99 0.00 0.36 0.00 0.40 0.00 0.32 0.00 -17.92 0.00 -9.78 0.09 0.20 0.00 0.14 0.00 -0.12 0.05 12.15 0.00 9.31 0.00 0.37 0.00 0.18 0.00 -0.08 0.21 10.94 0.00 4.58 0.19 0.19 0.00 -0.32 0.00 0.03 0.78 8.98 0.16 -10.26 0.17 0.25 0.00 0.47 0.00 -0.03 0.38 5.93 0.00 3.78 0.02 0.29 0.00 0.17 0.00 Table 10 - Loan-Level Regression Results for Refinance Loans 1997 Variable INTERCEPT INTERCEPT ASIAN ASIAN BLACK BLACK HISPANIC HISPANIC LN INCOME LN INCOME MISSING MISSING CAP RATE CAP RATE LN MED INCOME LN MED INCOME PCT RENT PCT RENT PCT COLLEGE PCT COLLEGE PCT ASIAN PCT ASIAN PCT BLACK PCT BLACK PCT HISPANIC PCT HISPANIC Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 1997 Baltimore 1997 Chicago 1997 Dallas 1997 Los Angeles 1997 New York City 1997 Philadelphia 1997 Whole Sample 1997 8.05 0.11 -1.74 0.10 0.45 0.00 -1.99 0.06 -0.84 0.00 1.45 0.00 4.31 0.38 -0.46 0.20 -0.23 0.75 0.39 0.77 12.93 0.00 2.07 0.00 0.62 0.66 32.21 0.00 -0.24 0.60 1.00 0.00 1.07 0.01 -0.73 0.00 1.57 0.00 -5.25 0.19 -2.75 0.00 -1.21 0.08 0.96 0.30 5.83 0.12 -0.38 0.34 -7.88 0.01 8.73 0.00 -0.13 0.21 1.02 0.00 -0.11 0.04 -0.52 0.00 1.22 0.00 -0.40 0.46 -0.67 0.00 -0.61 0.00 -0.30 0.31 0.44 0.33 1.16 0.00 0.93 0.00 -8.81 0.27 -0.58 0.28 0.47 0.04 -0.27 0.31 -0.63 0.00 1.04 0.00 3.42 0.36 0.64 0.32 0.85 0.18 -1.82 0.09 -5.11 0.04 1.90 0.00 -0.24 0.65 8.92 0.00 -0.40 0.00 0.74 0.00 0.05 0.34 -0.26 0.00 1.47 0.00 -4.68 0.09 -1.05 0.00 -1.05 0.00 0.68 0.08 -0.27 0.35 0.66 0.00 0.41 0.03 9.81 0.00 -1.12 0.00 0.48 0.00 0.00 0.99 -0.97 0.00 1.65 0.00 -4.38 0.03 -0.82 0.00 -0.98 0.00 -1.03 0.04 0.62 0.07 0.65 0.00 0.45 0.07 8.24 0.09 -0.91 0.00 0.87 0.00 0.03 0.85 -0.82 0.00 1.46 0.00 0.75 0.67 -0.87 0.04 -0.58 0.25 2.28 0.00 1.74 0.04 1.11 0.00 -0.01 0.97 9.43 0.00 -0.47 0.00 0.84 0.00 -0.05 0.16 -0.60 0.00 1.44 0.00 -1.01 0.03 -0.79 0.00 -0.75 0.00 0.18 0.27 0.07 0.68 1.06 0.00 0.72 0.00 Variable PCT VHIGH RISK PCT VHIGH RISK PCT NOINFO RISK PCT NOINFO RISK SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE MALE SINGLE MALE Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 1997 Baltimore 1997 Chicago 1997 Dallas 1997 Los Angeles 1997 New York City 1997 Philadelphia 1997 Whole Sample 1997 -25.00 0.00 11.90 0.15 -0.13 0.28 -0.03 0.81 4.18 0.72 -2.28 0.73 -0.30 0.00 -0.32 0.00 -5.64 0.02 -0.81 0.65 0.11 0.00 0.16 0.00 9.20 0.30 1.38 0.85 0.36 0.04 0.62 0.00 0.63 0.88 14.02 0.00 0.11 0.02 0.03 0.47 9.92 0.01 4.29 0.21 -0.21 0.00 0.02 0.71 4.53 0.40 7.52 0.14 -0.18 0.01 0.29 0.00 -0.96 0.47 1.34 0.25 0.00 0.84 0.10 0.00 Table 11 - Loan-Level Regression Results for Refinance Loans 2002 Variable INTERCEPT INTERCEPT ASIAN ASIAN BLACK BLACK HISPANIC HISPANIC LN INCOME LN INCOME MISSING MISSING CAP RATE CAP RATE LN MED INCOME LN MED INCOME PCT RENT PCT RENT PCT COLLEGE PCT COLLEGE PCT ASIAN PCT ASIAN PCT BLACK PCT BLACK PCT HISPANIC PCT HISPANIC Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 2002 Baltimore 2002 Chicago 2002 Dallas 2002 Los Angeles 2002 New York City 2002 Philadelphia 2002 Whole Sample 2002 -6.90 0.07 -0.39 0.41 1.07 0.00 0.47 0.15 -0.65 0.00 1.23 0.00 5.06 0.16 0.45 0.10 -0.49 0.33 -1.14 0.24 6.49 0.03 1.42 0.00 1.23 0.30 0.51 0.94 0.21 0.64 0.66 0.00 0.80 0.02 -0.78 0.00 1.29 0.00 4.33 0.32 -0.07 0.90 -1.21 0.08 -1.11 0.24 4.37 0.27 0.44 0.28 -1.91 0.48 0.97 0.55 0.03 0.72 1.35 0.00 0.74 0.00 -0.44 0.00 1.12 0.00 0.29 0.38 -0.21 0.13 -0.55 0.00 -1.53 0.00 -0.12 0.71 1.15 0.00 0.93 0.00 -7.69 0.00 -0.60 0.00 1.09 0.00 -0.28 0.00 -0.64 0.00 0.98 0.00 4.80 0.00 0.78 0.00 0.09 0.61 -3.37 0.00 0.91 0.24 1.60 0.00 0.78 0.00 -0.62 0.69 0.12 0.00 0.88 0.00 0.45 0.00 -0.05 0.01 0.19 0.00 8.42 0.00 -0.34 0.00 -0.29 0.05 -1.27 0.00 0.22 0.15 0.61 0.00 0.16 0.08 2.50 0.15 -0.47 0.00 0.60 0.00 0.53 0.00 -0.30 0.00 0.88 0.00 -4.73 0.00 -0.29 0.05 -0.74 0.00 -3.77 0.00 -0.35 0.07 0.59 0.00 0.19 0.15 -2.12 0.61 -0.33 0.07 0.38 0.00 -0.23 0.15 -0.57 0.00 0.47 0.00 3.57 0.04 0.15 0.69 -0.50 0.25 -0.28 0.64 0.11 0.89 0.86 0.00 0.05 0.90 -1.60 0.01 0.02 0.56 0.88 0.00 0.48 0.00 -0.35 0.00 0.70 0.00 0.22 0.38 -0.01 0.80 -0.29 0.00 -2.33 0.00 -0.04 0.67 0.82 0.00 0.34 0.00 PCT VHIGH RISK PCT VHIGH RISK PCT NOINFO RISK PCT NOINFO RISK SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE MALE SINGLE MALE Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq -4.32 0.45 13.16 0.03 -0.06 0.53 0.12 0.17 20.21 0.11 -13.98 0.05 0.00 0.97 0.20 0.03 -1.21 0.49 3.56 0.01 0.36 0.00 0.40 0.00 -6.18 0.04 5.80 0.01 0.21 0.00 0.15 0.00 8.24 0.00 4.56 0.01 0.37 0.00 0.18 0.00 7.39 0.00 1.11 0.55 0.19 0.00 -0.32 0.00 10.18 0.03 -8.52 0.04 0.25 0.00 0.47 0.00 5.13 0.00 2.57 0.00 0.29 0.00 0.17 0.00 Table 12 - Loan-Level Regression Results for Refinance Loans 1997 Variable INTERCEPT INTERCEPT ASIAN ASIAN BLACK BLACK HISPANIC HISPANIC LN INCOME LN INCOME MISSING MISSING CAP RATE CAP RATE LN MED INCOME LN MED INCOME PCT RENT PCT RENT PCT COLLEGE PCT COLLEGE PCT ASIAN PCT ASIAN PCT BLACK PCT BLACK PCT HISPANIC PCT HISPANIC DEF DEF Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 1997 Baltimore 1997 Chicago 1997 Dallas 1997 Los Angeles 1997 New York City 1997 Philadelphia 1997 Whole Sample 1997 11.53 0.04 -1.74 0.10 0.46 0.00 -1.98 0.06 -0.84 0.00 1.46 0.00 -1.92 0.78 -0.65 0.10 -0.42 0.57 0.18 0.89 8.14 0.14 1.79 0.01 1.32 0.39 0.03 0.19 34.81 0.00 -0.23 0.62 1.00 0.00 1.06 0.01 -0.73 0.00 1.57 0.00 -5.22 0.19 -3.01 0.00 -1.35 0.05 1.18 0.22 7.85 0.07 -0.35 0.38 -8.68 0.01 -0.01 0.34 7.66 0.00 -0.13 0.21 1.01 0.00 -0.11 0.03 -0.52 0.00 1.22 0.00 -0.40 0.45 -0.57 0.00 -0.56 0.00 -0.35 0.23 0.75 0.12 1.10 0.00 0.97 0.00 0.01 0.03 -9.22 0.26 -0.56 0.29 0.45 0.04 -0.28 0.29 -0.64 0.00 1.03 0.00 2.77 0.47 0.65 0.33 0.80 0.21 -1.62 0.14 -5.24 0.04 1.78 0.00 -0.14 0.80 0.02 0.32 7.04 0.01 -0.39 0.00 0.72 0.00 0.05 0.39 -0.26 0.00 1.47 0.00 -4.00 0.15 -0.84 0.00 -0.84 0.00 0.44 0.27 -0.08 0.78 0.58 0.01 0.37 0.04 0.02 0.00 9.54 0.00 -1.12 0.00 0.48 0.00 0.00 0.99 -0.96 0.00 1.65 0.00 -3.88 0.05 -0.79 0.00 -0.95 0.00 -1.00 0.04 0.73 0.03 0.55 0.01 0.40 0.10 0.01 0.09 9.56 0.06 -0.91 0.00 0.87 0.00 0.03 0.86 -0.82 0.00 1.46 0.00 0.49 0.79 -0.99 0.03 -0.69 0.19 2.39 0.00 1.82 0.03 1.14 0.00 -0.09 0.83 0.00 0.47 8.80 0.00 -0.47 0.00 0.83 0.00 -0.05 0.15 -0.60 0.00 1.44 0.00 -1.10 0.02 -0.73 0.00 -0.72 0.00 0.16 0.33 0.14 0.42 1.01 0.00 0.75 0.00 0.01 0.00 Variable PCT VHIGH RISK PCT VHIGH RISK PCT NOINFO RISK PCT NOINFO RISK SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE MALE SINGLE MALE Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 1997 Baltimore 1997 Chicago 1997 Dallas 1997 Los Angeles 1997 New York City 1997 Philadelphia 1997 Whole Sample 1997 -28.54 0.00 9.77 0.25 -0.13 0.27 -0.02 0.84 3.70 0.76 -0.20 0.98 -0.30 0.00 -0.32 0.00 -6.75 0.00 -0.14 0.94 0.11 0.00 0.16 0.00 10.55 0.24 1.82 0.81 0.35 0.04 0.62 0.00 -0.82 0.84 11.96 0.00 0.11 0.01 0.03 0.44 10.10 0.01 3.48 0.32 -0.21 0.00 0.02 0.73 4.73 0.38 7.62 0.13 -0.18 0.01 0.29 0.00 -1.48 0.28 1.17 0.32 0.00 0.86 0.10 0.00 Table 13 - Loan-Level Regression Results for Refinance Loans 2002 Variable INTERCEPT INTERCEPT ASIAN ASIAN BLACK BLACK HISPANIC HISPANIC LN INCOME LN INCOME MISSING MISSING CAP RATE CAP RATE LN MED INCOME LN MED INCOME PCT RENT PCT RENT PCT COLLEGE PCT COLLEGE PCT ASIAN PCT ASIAN PCT BLACK PCT BLACK PCT HISPANIC PCT HISPANIC DEF DEF Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 2002 Baltimore 2002 Chicago 2002 Dallas 2002 Los Angeles 2002 New York City 2002 Philadelphia 2002 Whole Sample 2002 -6.86 0.08 -0.39 0.41 1.07 0.00 0.47 0.15 -0.65 0.00 1.23 0.00 4.92 0.36 0.45 0.11 -0.49 0.33 -1.15 0.25 6.39 0.12 1.42 0.00 1.25 0.33 0.00 0.97 6.70 0.35 0.21 0.64 0.65 0.00 0.79 0.02 -0.78 0.00 1.28 0.00 4.33 0.32 -0.68 0.30 -1.49 0.03 -0.76 0.42 9.27 0.04 0.55 0.18 -4.04 0.15 -0.02 0.02 0.73 0.66 0.03 0.73 1.35 0.00 0.74 0.00 -0.44 0.00 1.12 0.00 0.28 0.39 -0.19 0.20 -0.54 0.00 -1.55 0.00 -0.07 0.84 1.14 0.00 0.94 0.00 0.00 0.62 -7.40 0.00 -0.59 0.00 1.10 0.00 -0.28 0.00 -0.65 0.00 0.98 0.00 4.87 0.00 0.76 0.00 0.10 0.60 -3.32 0.00 0.86 0.27 1.58 0.00 0.77 0.00 0.00 0.81 -0.78 0.62 0.12 0.00 0.88 0.00 0.45 0.00 -0.05 0.01 0.19 0.00 8.58 0.00 -0.32 0.01 -0.26 0.09 -1.29 0.00 0.24 0.13 0.60 0.00 0.16 0.10 0.00 0.37 1.82 0.30 -0.47 0.00 0.60 0.00 0.53 0.00 -0.30 0.00 0.88 0.00 -4.15 0.00 -0.23 0.12 -0.64 0.00 -3.81 0.00 -0.22 0.27 0.44 0.00 0.12 0.37 0.01 0.00 -0.37 0.93 -0.33 0.07 0.38 0.00 -0.23 0.15 -0.57 0.00 0.47 0.00 3.25 0.06 -0.01 0.98 -0.63 0.15 -0.17 0.79 0.27 0.76 0.89 0.00 -0.05 0.90 -0.01 0.20 -1.74 0.01 0.02 0.57 0.88 0.00 0.48 0.00 -0.35 0.00 0.70 0.00 0.21 0.42 0.00 0.99 -0.27 0.00 -2.33 0.00 -0.03 0.74 0.80 0.00 0.35 0.00 0.00 0.04 Variable PCT VHIGH RISK PCT VHIGH RISK PCT NOINFO RISK PCT NOINFO RISK SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE MALE SINGLE MALE Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Estimate ProbChiSq Atlanta 2002 Baltimore 2002 Chicago 2002 Dallas 2002 Los Angeles 2002 New York City 2002 Philadelphia 2002 Whole Sample 2002 -4.34 0.45 13.12 0.03 -0.06 0.53 0.12 0.17 17.23 0.17 -8.06 0.28 0.00 0.97 0.20 0.03 -1.39 0.43 3.64 0.01 0.36 0.00 0.40 0.00 -6.17 0.04 5.52 0.01 0.20 0.00 0.15 0.00 7.66 0.00 4.45 0.02 0.37 0.00 0.18 0.00 8.10 0.00 -0.65 0.73 0.19 0.00 -0.33 0.00 10.72 0.02 -8.86 0.04 0.25 0.00 0.47 0.00 4.93 0.00 2.46 0.00 0.29 0.00 0.17 0.00 Figure 1 - Decline in Sub-prime Lending Sub-prime Lending Share, 1997 Change in Sub-prime Lending Share, 1997-2002 Figure 2 - Philadelphia Subprime Lending Share of Total Loan Volume 1997 (1997 Quintile Breaks) 2002 (1997 Quintile Breaks)