Neighborhood Patterns of Subprime Lending: Evidence from Disparate Cities

advertisement

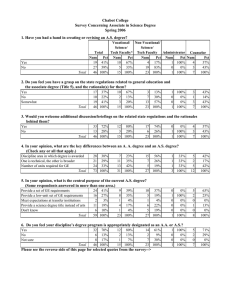

Neighborhood Patterns of Subprime Lending: Evidence from Disparate Cities Paul S. Calem Division of Research and Statistics Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Jonathan E. Hershaff Division of Research and Statistics Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Susan M. Wachter The Wharton School University of Pennsylvania June 8, 2004 The views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent official views of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors or its staff. We thank Robert Avery, Glenn Canner for very helpful comments. 1 Abstract This paper estimates, for 7 cities, a model of prime versus subprime allocation of loans in 1997 and 2002 based on both individual loan and neighborhood attributes. The paper is directly interested in the effect of neighborhood racial and ethnic composition on the likelihood of receiving a subprime loan. The paper also allows for interaction of borrower race and ethnicity with neighborhood attributes. A unique feature of the paper is that it provides additional neighborhood controls for the aggregate level of credit risk and the neighborhood level of equity risk. The paper finds some evidence for tightening loan standards over the 5-year period in the subprime market. In both years, even with risk controls, the minority share of neighborhood is consistently significant and positively related to subprime share. Furthermore, neighborhood education level is consistently significant and negatively related to subprime lending. Keywords: Subprime mortgages; Mortgage lending and race; Mortgage lending and neighborhood 2 I. Introduction Subprime residential mortgage lending, characterized by relatively high credit risk and high interest rates or fees has grown substantially in recent years, both in total volume and as a share of overall mortgage lending. On the one hand, this growth represents an expansion in the supply of mortgage credit among households who do not meet prime market underwriting standards and, hence, might not otherwise have access to credit. On the other hand, the high cost of subprime credit has prompted concerns that its rapid growth may in part be due to sales tactics of lenders (“targeting”) or to a lack of financial sophistication among classes of borrowers that lead some borrowers to pay more than is necessary for credit (Courchane et al. 2004). At the same time, high default and foreclosure rates among subprime borrowers have prompted concerns that it may not be in the best interest of some borrowers or of the neighborhoods where they reside for such loans to be extended in the first place. The growth of subprime lending and the ensuing debate over its role has attracted the interest of policymakers and academic researchers. A number of empirical studies have analyzed the degree to which subprime lending correlates with neighborhood economic and demographic characteristics. Such studies are of interest because high subprime default rates are more likely to have adverse consequences for communities to the extent that subprime loans are concentrated in neighborhoods that are fundamentally more vulnerable to economic decline. Further, such studies are of interest because a correlation with neighborhood demographic characteristics may reflect “targeting” through more intensive marketing of subprime products to selected populations.1 1 Arguably, such a process of “targeting” is more plausible than that where bank employees consciously persuade individual minority customers to apply for subprime loans. 3 In this study, we conduct a detailed analysis of subprime mortgage lending patterns in seven major cities (Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles, New York, and Philadelphia), representing a cross section of the nation as a whole. The analysis is conducted separately for 2002, the most recent year for which required data are available, and 1997 to assess the degree to which lending patterns may be evolving. We examine the relative likelihood that a conventional, refinance loan is subprime in relation to a variety of neighborhood demographic and economic variables, controlling for a number of individual borrower demographic and economic characteristics. The study extends earlier work by Calem, Gillen, and Wachter (CGW).2 The earlier study was limited to two cities and one year (Chicago and Philadelphia in 1999). The present study also looks more closely at the demographic correlates of subprime lending, through examination of the interaction between neighborhood and individual borrower demographic classifications. Most studies to date examine subprime mortgage lending in relation to a limited set of neighborhood or individual demographic variables. Relatively few studies, however, include both individual borrower characteristics and measures of neighborhood risk. A recent study published by NCRC and a study by Apgar (2004) et al. partially replicate the CGW methodology; the former does not include individual characteristics while the latter incorporates a more limited set of neighborhood variables.3 Similarly, Scheessele (2002) incorporates a variety of neighborhood variables but also does not control for individual characteristics. Pennington-Cross, Yezer, and Nichols (2002) use a broad range of individual characteristics, including borrower credit rating, but only one neighborhood variable (an indicator for “traditionally underserved” neighborhood), and restrict attention to home purchase loans 2 See Calem, Gillen, and Wachter, Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, forthcoming. 4 originated in 1996 (whereas subprime mortgage loans are predominantly used for refinancing). The present study incorporates a broad set of neighborhood variables and individual borrower demographic characteristics, including a measure of property equity risk and a measure of the credit quality composition of neighborhood residents.4,5 The paper is organized as follows: Section II reviews the existing literature in greater detail. Section III describes the sources of data, variables, and statistical approach for the analysis. Section IV presents the results and Section V concludes. II. Literature Review Subprime lending has grown rapidly over the past decade, which has increased policy and research interest in the distribution of subprime lending across borrowers and neighborhoods. Early studies show striking positive correlations between minority borrowers and frequency of subprime lending and also between predominantly minority neighborhoods and frequency of subprime lending. For example, Canner, Passmore, and Laderman (1999) report that in 1998, more than 15 percent of loans to black households or in predominantly black neighborhoods were subprime, compared with the only 6 percent of loans that were subprime overall. They also present evidence that subprime lending has increased the amount of credit available to low- or moderate-income and minority households and to residents of low- or moderate-income and predominantly minority neighborhoods. They attribute more than one-third of the growth in 3 Unlike Calem & Wachter, the NCRC study is estimated on metropolitan data using which combines urban and suburban markets with potentially different outcomes. 4 Unlike Pennington-Cross et al., however, we do not have access to individual borrower risk measures. 5 The measure used as a proxy for equity risk is the neighborhood rent to value ratio. Tootell (QJE, 1996) and Ross and Tootell (JUE, 2004) both show that rent to value ratio is the most important neighborhood predictor of underwriting outcomes. Deng, Ross, and Wachter (RSUE, 2003) show that a similar equity risk proxy is important in explaining homeownership. 5 overall mortgage lending to predominantly minority Census tracts between 1993 and 1998, and about one-fourth of the growth in lower income areas, to subprime lending. Similar patterns are demonstrated by Immergluck and Wiles (1999), who provide an analysis of lending patterns over time in Chicago in the late 1990s. They find that subprime lending had been increasing in share in neighborhoods with large minority populations. Bunce et al. (2000) calculate relative frequencies of subprime refinance lending in predominantly minority neighborhoods and low- or moderate-income neighborhoods nationally and for five individual metropolitan areas (New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Atlanta, and Los Angeles) in 1999, again without control variables. This study finds that on average nationwide, frequency of subprime lending was three times higher in low-income neighborhoods than in upper-income neighborhoods, and five times higher in predominantly black neighborhoods than in predominantly white neighborhoods. The study also finds that in black neighborhoods, half of all refinance loans were subprime, compared to only one out of every 10 in white neighborhoods.6 While these early studies demonstrate that minority and low-income status of borrowers and neighborhoods are associated with a higher frequency of subprime lending, they do not control for other possible explanatory factors, such as borrower credit risk or other neighborhood characteristics. More recent studies have improved on the methods used to identify neighborhood concentration of subprime lending in early research. Scheessele (2002) identifies the type of neighborhoods in the nation as a whole where borrowers are likely to rely on subprime loans for refinancing. The paper finds that, even after controlling for several neighborhood characteristics (but not for the credit quality distribution of neighborhood residents), the percentage of African 6 In New York, 60 percent of refinance loans in predominantly black neighborhoods were subprime, 52% in Chicago, 49 % in Baltimore, and 33% in Atlanta and Los Angeles. 6 Americans in a given neighborhood is positively related to the share of refinance loans that are subprime. Also using nationwide data from 1996, Pennington-Cross, Yezer, and Nichols (2002) analyze the factors associated with whether a borrower obtained a subprime, prime, or FHA mortgage when obtaining a home-purchase loan (although they do not analyze refinance loans). A major innovation of the study is that it incorporates measures of individual borrower credit risk, using data from a major national credit bureau that was linked (based on Census tract location, loan amount, and lender identification) with HMDA data. The analysis relates differences across metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) to MSA level variables but only includes one tract level variable: a dummy variable identifying “underserved” (low income and predominantly minority) neighborhoods. After including these controls for borrower risk, the study finds that subprime mortgages are not necessarily more prevalent in these “underserved” neighborhoods or among lower income borrowers, but they are more prevalent among minority borrowers. In a recent study, CGW examines how subprime lending activity varies with a broad range of neighborhood economic and demographic characteristics within Philadelphia and Chicago. Regression equations are estimated at the Census tract level, where the dependent variable is share of HMDA-reported conventional loans that are subprime, and logit equations are estimated at the borrower level, where the dependent variable is whether or not an originated loan is subprime and where individual demographic characteristics are included for both homepurchase and refinance loans. Statistically significant relationships are observed between subprime lending and the credit quality composition of neighborhood residents and other neighborhood economic variables. The study yields mixed results with respect to the relationship between subprime lending activity and the minority composition of neighborhoods. 7 In particular, in the borrower-level analysis, a statistically significant association with percent African-American homeowner population is observed only for Chicago. The National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC 2003) partially replicates the CGW study analyzing subprime lending in ten large metropolitan areas. The analysis is conducted only at the Census tract level (individual characteristics are not included). Regression equations are estimated, where the dependent variable is the proportion of HMDA-reported conventional loans that are subprime, and the independent variables are Census tract characteristics. As in CGW, measures of the credit-quality composition of neighborhood residents are included along with a number of neighborhood economic and demographic variables. The NCRC study finds that, in nine of the ten cities7, the proportion of subprime refinance lending increased as the proportion of minorities in a neighborhood increased, all else equal. For home-purchase subprime lending, this relationship was seen in six of the ten cities. Apgar et al. (2004) extend this analysis to more MSAs, replicating the logistic analysis of CGW, but with a more limited set of neighborhood variables. In particular, they do not include measures of the credit-quality composition of neighborhood residents. They find that the proportion of minorities in a neighborhood is significant and negatively related to the market share of prime lenders. III. Data Sources, Variables, and Statistical Approach Data used in this analysis comes from four primary sources. First, we use data collected by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) in accordance with the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) to obtain mortgage-loan information and borrower-level 7 Specifically, the NCRC study looked at Atlanta, Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, New York, St. Louis and Washington, D.C. 8 characteristics for 1997 and 2002.8 Second, like all previous studies, we use the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) annual lists of HMDA-reporting lenders that specialize in subprime loans.9 Third, we use the 2000 Census to construct Census variables and measures of neighborhood-related credit risk for Census tracts. Finally, we obtain information on the distribution of credit ratings of individuals within tracts from CRA Wiz®, a product of PCI Services in Boston that provides comprehensive, geography-based information. This information is available to us only for 1999. The original source of these ratings distributions for CRA Wiz® is the consumer credit reporting agency Experian. Under HMDA, lending institutions with more that $30 million in assets and that have branches in MSAs are required to provide information about their mortgage loan applications. This information includes type of loan, the purpose of the loan, the dollar amount of the loan, the Census tract where the home is located, and whether the application was approved or denied. Demographic information on the applicant is also provided, including income, gender, and race or ethnicity. Each loan application is also coded to identify the lending institution to which the applicant applied. Since the HMDA data do not separately identify subprime loans, loans originated by these institutions are used as a proxy for subprime loans. That is, any loan originated by a lender on the HUD list of subprime specialists is classified by us as subprime; all other loans are considered prime. Lenders on the HUD list either identified themselves as subprime lenders or had more than fifty percent of their originated conventional mortgages classified as subprime. Significant potential measurement error due to the omission of smaller lenders that do not report under HMDA and to the inability to classify loans of lenders that originate both types of loans is 8 9 We also use 1999 HMDA data for supplemental analysis, referred to below. www.huduser.org/datasets/manu.html 9 unavoidable (Lax, Manti, Raca, Zorn, 2000). Using our approach, some prime loans will be classified as subprime, and any subprime loans from large lenders that have less than half of their business in the subprime market will be incorrectly classified as prime. Such misclassifications could potentially introduce measurement error. Thus, since HMDA data exclude small lenders, our analysis may be subject to measurement error to the extent that lenders not reporting under HMDA originate a substantial share of subprime loans. However, with the information that is available at this time, our approach comes as close as is possible to measuring relative frequency of origination of subprime compared to prime loans. Census tract definitions in the 2000 Census are often inconsistent with the 1990 Census tract definitions employed in 2002 HMDA data and the CRA Wiz® data. To reconcile these differences, we employed a special database providing demographic characteristics based on the 2000 Census for Census tracts as defined in 1990.10 Neighborhood characteristics. From the 2000 Census, we obtain a number of tract-level economic and demographic variables for use in the analysis. These include the log of tract median family income (LNMFI), the percent of individuals 25 years of age or older with a bachelor’s degree (PCT_COLLEGE), and the proportion of occupied housing units that are renter-occupied (PCT_RENTAL). Since economic conditions tend to be better in neighborhoods where residents have higher incomes or educational attainment, and since borrower financial sophistication tends to be inversely related to educational attainment, we expect subprime borrowing to be inversely related to these variables. Three measures of percent minority population: the percent of households headed by a person classified as African American, the percent headed by a person classified as Asian, and the percent headed by a person classified as Hispanic, (respectively PCT_BLACK; PCT_ASN_HISP), also are used. 10 A proxy for the price of risk in real estate investment, the tract’s capitalization rate (CAP_RATE), defined as a ratio of the tract’s annualized median rent divided by the median house value, also is constructed using 2000 Census data. A larger value for this measure is consistent with lower expected price appreciation or more uncertain future house prices and, hence, indicates increased credit risk. Hence, we expect this variable to be positively associated with relative likelihood of a loan being subprime. Using CRA Wiz®, we calculate two measures of the credit quality composition of neighborhood residents. These are the percent of adult individuals in a tract that have been classified as very high credit risk (PCT_VHIGH_RISK), defined as the bottom quintile of the credit rating distribution, and the percent with no credit rating (PCT_NA_RISK). Both are expected to be positively associated with relative likelihood of a loan being subprime. Individual borrower characteristics. From HMDA, we obtain borrower-specific demographic variables for use in the analysis. We create dummy variables identifying AfricanAmerican, Asian-American, and Hispanic borrowers (BLACK, ASIAN, HISPANIC, respectively) and those for whom race is unreported (MISSING). In addition, we separately identify single borrowers (those without co-borrowers) and then create dummy variables classifying these borrowers by gender (SINGLE MALE; SINGLE FEMALE). From HMDA, we also obtain the natural log of the borrower’s income (LNINCOME). Statistical models. Logit models are estimated where the dependent variable is whether or not a HMDA-reported loan is subprime (SUBPRIME); that is, is originated by a lender on the HUD list. Loans having dollar amounts larger than the conforming size limit for the year of analysis are excluded, since such loans are unlikely to be subprime quality. 10 See Avery, Calem, and Canner (2003) for a description of this database. 11 For each city and year, two models are estimated. The first includes, as independent variables, each of the variables defined above. In the second specification, we account for interactions between neighborhood and individual demographic characteristics. Interaction terms are included to potentially shed light on the source of any association between the percent African-American and minority population of a neighborhood and subprime borrowing. That is, we replace the Census tract demographic variable PCT_BLACK with a set of five measures representing the interaction of this variable with each of the individual borrower race classifications. Thus, PCT_BLACK is interacted with, respectively, BLACK, HISPANIC, ASIAN, MISSING, and a dummy variable (WHITE) that identifies whites and others. In addition, we replace PCT_VHIGH_RISK and PCT_NA_RISK with the respective interactions of these variables with the individual borrower race classifications. IV. Logistic Estimation Results Mean values of the explanatory variables in each city for 1997 and 2002 are reported in Table 1 (where statistics for borrower and neighborhood median income are reported prior to applying the log transformation). The table indicates a few notable distinctions between the two years. The average income of borrowers was substantially higher in 2002 compared to 1997, and borrowers in 2002 were less likely to be members of minority groups.11 Similarly, borrowers in 2002 resided in higher-income areas and areas with larger proportions of college graduates and lower percentage minority populations. Moreover, a smaller percentage of loans were subprime in 2002 compared to 1997. These differences likely reflect the relatively large proportion of 11 The average income of borrowers is substantially higher in 2002 compared to 1997 even after adjusting the nominal figures reported in Table 1 for inflation (using the GDP deflator of 1.12). 12 refinance mortgages originated in 2002, and also in part may reflect trends over the intervening period.12 Table 1 also highlights differences across individual cities, most notably in minority composition and in the frequency with which borrower race is unreported. For instance, Baltimore and Atlanta have relatively high percentages of African-American borrowers and relatively few Hispanic or Asian borrowers, while Los Angeles has a relatively high percentage of Hispanic borrowers. The cities differ along other dimensions as well. In 2002, for example, the mean borrower in Atlanta was in a Census tract where about half the adult population had a college degree, while the mean borrower in Philadelphia was in a Census tract where about one quarter of the adult population had a college degree. Tables 2a and 2b report estimation results for the first model (no interaction terms). Overall, we observe consistency across cities and years with our a priori expectations. In each city and year, neighborhood educational attainment (PCT_COLLEGE); neighborhood median income (LNMFI); and borrower income (LINCOME), when statistically significant, are inversely associated with subprime borrowing. Also, in each city and year, the estimated coefficients on neighborhood credit quality (PCT_VHIGH_RISK, PCT_NA_RISK) and property risk (CAPRATE) are positively associated with subprime borrowing when statistically significant. We observe some differences across years with respect to degree of consistency across cities. In 2002, in every city the relative likelihood of a loan being subprime is inversely related to the proportion of neighborhood residents with a bachelor’s degree, while in 1997, this relationship holds for three cities. CAPRATE is positively associated with a loan being 12 For example, there were modest declines in the proportion of black borrowers (from 29 to 25 percent) and the percentage of loans that were subprime (from 33 to 26 percent) between 1997 and 1999. 13 subprime in three cities in 1997 and four cities in 2002. The neighborhood credit quality measures are more strongly related to relative likelihood of a loan being subprime in 1997 compared to 2002. In particular, PCT_VHIGH_RISK is statistically significant and positively related to the relative likelihood of a loan being subprime for five cities in 1997 but for only two cities in 2002. This may reflect a tightening of subprime credit standards in more recent years, observed, for example, by Chomsisengphet and Pennington-Cross (2004).13 We find that Census tract percent African-American population (PCT_BLACK), AfricanAmerican borrower (BLACK), and the indicator for missing race information (MISSING) are consistently, positively associated with relative likelihood of a loan being subprime. Results for other minority categories are more mixed. Census tract percent Asian or Hispanic, when statistically significant, is positively associated with relative likelihood of a loan being subprime. In some cases, however, Hispanic or Asian borrower is inversely associated with relative likelihood of a loan being subprime.14 Single borrower (male or female) tends to be positively associated with relative likelihood of a loan being subprime. Tables 3a and 3b report estimation results for the second model, which contains the interaction terms. Only results pertaining to the interaction terms are reported, other results are similar to those shown in Tables 2a and 2b. A striking finding is that the positive association observed in Tables 2a and 2b between subprime lending and the percent African-American population of a neighborhood is particularly strong among white borrowers. The estimated coefficient on the interaction between PCT_BLACK and WHITE is positive and statistically 13 Supplemental analysis conducted with 1999 HMDA data yielded results quite similar to those for 2002, except in the case of the neighborhood credit quality measures, which were more consistently associated with relative likelihood of subprime lending, as in 1997. The 1999 results are available from the authors upon request. 14 We also included percent of population over 65 as a measure of targeting to the elderly. This variable was not significant. Results were robust to the inclusion of age variables and also were robust to the exclusion of various other variables such as single status and missing race. 14 significant in each city in both years, and is consistently substantially larger than the estimated coefficient on the interaction between PCT_BLACK and minority race categories (which often are not statistically significant). Similarly, the estimated coefficient on the interaction between PCT_BLACK and HISPANIC is usually statistically significant and, when it is, is positive and comparable in magnitude to the estimated coefficient on WHITE. What do these findings imply? We find the strong association between educational attainment of neighborhood residents and subprime borrowing to be of particular interest. This result suggests that to some extent, lack of financial sophistication may lead borrowers to choose subprime products. In turn, this suggests that financial education might be effective in helping borrowers obtain lower cost credit. Alternatively, PCT_COLLEGE may simply be a relatively robust measure of credit risk at the neighborhood level. Once again, however, this variable is consistently associated with subprime lending even after the inclusion of risk and interact variables. We also test for interaction terms by including borrower minority status interacted with neighborhood status. We find a significant interaction of white with percent black. A likely explanation is that whites with poor credit history buy homes in predominantly minority neighborhoods15. However, this result also is consistent with institutions active in subprime lending targeting their lending efforts to minority neighborhoods, either directly or through broker networks.16 The strong association between CAP_RATE and subprime borrowing in a subset of cities suggests that subprime lenders to some degree may be extending credit in areas where prime 15 See Schill and Wachter (1994) and Lundberg and Startz (2002) for similar results. Since black borrowers, wherever their neighborhood, are relatively more likely to choose or obtain subprime loans, targeting of African-American neighborhoods by subprime lenders may increase subprime borrowing among non-black borrowers more than among black borrowers. 16 15 lenders are hesitant to lend due to risks related to property value. Such risks may be more significant in some cities than in others. Finally, the results pertaining to missing race information are interesting. One conceivable interpretation of the correlation between subprime loans and missing race information particularly in minority neighborhoods is that brokers are more active in minority neighborhoods and are less apt to report race information. Moreover, the results suggest that HMDA data may be less useful for screening subprime lenders for potential discriminatory patterns than for screening prime lenders17. Policy implications. The strong association between the racial or ethnic composition of a neighborhood and relative likelihood of subprime borrowing suggests that enforcement of fair lending laws in the subprime market should remain a priority. Our results cannot be construed as evidence of discriminatory practices; as noted, they are consistent with a variety of alternative scenarios. They do however, indicate, that concerns about fair lending cannot be dismissed, and continued vigilance is required. For instance, lenders or brokers failing to inform potential borrowers located in minority neighborhoods of the full range of loan products available to them would raise fair lending concerns. Recently, the Federal Reserve Board tightened rules for collecting and reporting race and ethnicity information in applications taken by telephone, with the intended effect of reducing the incidence of missing race and ethnicity information in mortgage applications. The greater availability of race and ethnicity information would enhance fair lending enforcement 17 The results follow earlier findings concerning missing race information in HMDA. Holloway and Wyly (Economic Geography, 2002) discuss this issue in detail. Dietrich (OCC working paper, 2001) finds higher denial rates for the sample of loans where race is not reported, and even more convincingly Ross and Yinger (2002, MIT Press) find evidence of higher levels of racial discrimination (e.g. after controlling for underwriting variables) for the portion of the Boston Fed sample that could not be matched to HMDA data (where missing race information was the most common cause for why a match could not be obtained). See also Huck (2001). 16 opportunities and would allow all parties a greater ability to monitor developments in the subprime market. The observed relationship between educational attainment in a neighborhood and likelihood of subprime borrowing suggests that some subprime borrowers may be receiving less favorable loan terms than are potentially available to them, due to a lack of financial sophistication. This interpretation suggests a continuing policy focus on financial education as a tool for ensuring equal access to the prime market to all borrowers of prime credit quality. V. Conclusion This paper tests for neighborhood patterns of subprime lending in the distribution of subprime mortgage loans over time and across multiple cities. We include measures of neighborhood composition by race and ethnicity along with measures of neighborhood risk. We also include a measure of neighborhood education levels; an important policy question raised in the discussion of subprime lending is the extent to which financial sophistication or the lack there of influences the likelihood of subprime borrowing. A major focus of this paper is the impact of race and ethnicity of neighborhood, controlling for neighborhood risk and individual borrower characteristics. Results of logistic estimations show that individual race, ethnicity, and income are significant and positively related to the likelihood of subprime borrowing, along with single borrower (no co-borrower) status. Because we lack individual credit risk measures, we expect to find individual borrower race and ethnicity status variables to be significant. We have no a priori expectations regarding the relationship of minority status of neighborhood to subprime borrowing, assuming we have adequately controlled for sources of risk at the neighborhood level. Yet in each of the seven cities and for both periods, we find that minority status is significantly related to subprime 17 borrowing. In addition, the result pertaining to missing race information is interesting, and suggests that HMDA data may be less useful for screening subprime lenders for potential discriminatory patterns than for screening prime lenders, although newly instituted HMDA reporting rules may help dispel such concerns. We also find, across the seven cities and in both years, education levels are consistently related to subprime lending, all else equal. Relative likelihood of subprime borrowing tends to be inversely associated with neighborhood median income and positively associated with the neighborhood rent to value ratio, a measure of equity risk. Key variables measuring borrower credit risk by neighborhood tend to be positively related to subprime borrowing, although more strongly in 1997 than in 2002. These results are consistent with the neighborhood risk literature which shows that default and foreclosure rates are related to both property risk and individual credit quality (Calem and Wachter, 1999). The apparent increasing impact of neighborhood equity risk variables and decreasing impact of neighborhood credit risk on subprime borrowing over time are consistent with a trend towards more conservative credit quality standards in underwriting. The observed patterns are subject to the caveat that we cannot directly identify subprime loans but must rely as a proxy on the lender’s identity as a subprime specialist as determined by HUD. Thus, to some extent the observed patterns may simply reflect the historical lending patterns of these institutions. 18 Bibliography Apgar, William, Allegra Calder, and Gary Fauth. (2004). “Credit, Capital and Communities: The Implications of the Changing Mortgage Banking Industry for Community Based Organizations.” Joint Center for Housing Studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Avery, Robert B., Paul S. Calem, and Glenn B. Canner. (2003). “The Effects of the Community Reinvestment Act on Local Communities.” Draft, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve. Avery, Robert B., Raphael W. Bostic, Paul S. Calem, and Glenn B. Canner. (2000). “Credit Scoring: Issues and Evidence from Credit Bureau Files.” Real Estate Economics 28: 523-47. Avery, Robert B., Patricia E. Beeson, and Mark S. Sniderman. (1999). “Neighborhood Information and Home Mortgage Lending.” Journal of Urban Economics 45(2): 287-310. Bunce. (2000). Curbing Predatory Home Mortgage Lending. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Working Paper Series. Brueckner, Jan K. (1994). “The Demand for Mortgage Debt: Some Basic Results.” Journal of Housing Economics 3(4), December. Calem, Paul S. (1993). “The Delaware Valley Mortgage Plan: Extending the Reach of Mortgage Lenders.” Journal of Housing Research 4, 337-358. Calem, Paul S. (1996). “Mortgage Credit Availability in Low- and Moderate-Income Minority Neighborhoods: Are Information Externalities Critical?” The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 13(1): 71-89. Calem, Paul S. (1996). “Patterns of Residential Mortgage Activity in Philadelphia’s Low- and Moderate-Income Neighborhoods.” Mortgage Lending, Racial Discrimination, and Federal Policy, editors John Goering and Ron Wienk. Washington D.C., The Urban Institute Press, 671676. Calem, Paul S., and Susan Wachter. (1999). “Community Reinvestment Portfolio and Credit Risk: Evidence from an Affordable Home Loan Program.” Real Estate Economics 27(1), pp.105134. Calem, Paul S., Kevin Gillen and Susan Wachter. (2003). “The Neighborhood Distribution of Subprime Mortgage Lending.” Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, forthcoming 2004. Canner, Glenn B. and Elizabeth Laderman (1999). “The Role of Specialized Lenders in Extending Mortgages to Lower-Income and Minority Homebuyers.” Federal Reserve Bulletin, November. Cho, Man and Isaac Megbolugbe. (1996). “An Empirical Analysis of Property Appraisal and Mortgage Redlining.” The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 13(1): 45-55. 19 Chomsisengphet, Souphala, and Anthony Pennington-Cross. “Borrower Cost and Credit Rationing in the Subprime Mortgage Market,” Office of Housing Enterprise Oversight (February 2004). Courchane, Marsha J., Brian J. Surette, and Peter M. Zorn. (2004). “Subprime Borrowers: Mortgage Transitions and Outcomes.” Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, Forthcoming. Deng, Yongheng, Stephen Ross, and Susan M. Wachter. (2003). “Racial Differences in Homeownership: The Effect of Residential Location.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 33(5):517-556. Dietrich, Jason. (2001). “The Effects of Choice-based Sampling and Small-sample Bias on Past Fair Lending Exams.” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, E&PA Working Paper. Farley, R. (1996). “Racial Differences in the Search for Housing: Do Whites and Blacks Use the Same Techniques to Find Housing?” Housing Policy Debate 7(2): 367-285. Follain, James R. Mortgage Choice. (1990). AREUEA Journal, 18(2): 125-44. Gabriel, S. and S. Rosenthal. (1991). “Credit Rationing, Race, and the Mortgage Market.” Journal of Urban Economics 29(3): 371-379. Guttentag, Jack. (2001). “Another View of Predatory Lending.” Wharton Financial Institutions Center Paper 01-23-B. Hendershott, P., W. LaFayette and D. Haurin. (1997). “Debt Usage and Mortgage Choice: The FHA-Conventional Decision.” Journal of Urban Economics 41(2): 202-217. Holloway, Steven R. (1998). “Exploring the neighborhood contingency of race discrimination in mortgage lending in Columbus, Ohio.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88(2):252-276. Holloway, Steven R., and Elvin K. Wyly. (2001). “The Color of Money Expanded: Geographically Contingent Mortgage Lending in Atlanta.” Journal of Housing Research 12(1):55-90. Huck, Paul. (2001). “Home Mortgage Lending by Applicant Race: Do HMDA Figures Provide a Distorted Picture?” Housing Policy Debate 12(4):719-736. Immergluck, Daniel and Marti Wiles. Two Steps Back: The Dual Mortgage Market, Predatory Lending, and the Undoing of Community Development. Chicago, IL. November 1999. Jones, Lawrence D. (1993). “The Demand for Home Mortgage Debt.” Journal of Urban Economics 33(1): 10-28. 20 Kim-Sung, Kellie K. and Sharon Hermanson. (2003). “Experience of Older Refinance Mortgage Loan Borrowers: Broker- and Lender-Originated Loans,” AARP Public Policy Institute, Data Digest, January. Lang, William W., and Leonard I. Nakamura. (1993). “A Model of Redlining.” Journal of Urban Economics 33: 371-379. Lax, Howard, Michael Manti, Paul Raca, and Peter Zorn. (Forthcoming). “Subprime Lending: An Investigation of Economic Efficiency.” Working Paper, Freddie Mac. February 25, 2000. Li, Ying, and Eric Rosenblatt. (1997). “Can Urban Indicators Predict Home Price Appreciation? Implications for Redlining Research.” Real Estate Economics. 25(1). Ling, David C. and Susan M. Wachter. “Information Externalities and Home Mortgage Underwriting,” Journal of Urban Economics 44(3): 317-332. Lundberg, Shelly, and Richard Startz. (2002). “Race, Information, and Segregation.” National Community Reinvestment Coalition. (2003), “The Broken Credit System: Discrimination and Unequal Access to Affordable Loans by Race and Age: Subprime Lending in Ten Large Metropolitan Areas,” Washington, D.C.: National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Pennington-Cross, Anthony. (2002). “Subprime Lending in the Primary and Secondary Markets.” Journal of Housing Research 13(1): 31-50. Pennington-Cross, Anthony and Joseph Nichols. (2000). “Credit History and the FHA Conventional Choice.” Real Estate Economics 28(2): 307-336. Pennington-Cross, Anthony, Anthony Yezer and Joseph Nichols. (2000). “Credit Risk and Mortgage Lending: Who Uses Subprime and Why?” Research Institute for Housing America, Working Paper No. 00-03. Phillips, Robert F. and Anthony M.J. Yezer. (1996). “Self-Selection and Tests for Bias and Risk in Mortgage Lending: Can You Price the Mortgage If You Don’t Know the Process?” Journal of Real Estate Research 11(1): 87-102. Rachlis, Mitchell B. and Anthony M.J. Yezer. (1993). “Serious Flaws in Statistical Tests for Discrimination in Mortgage Markets.” Journal of Housing Research 4(2): 315-36. Ross, Stephen L., and Geoffrey M. B. Tootell. (2004). Journal of Urban Economics. Ross, Stephen L., and John Yinger. (2002). The Color of Credit: Mortgage Discrimination, Research Methodology, and Fair-Lending Enforcement. MIT Press. 21 Scheessele, Randall M. (1998). “1998 HMDA Highlights.” Housing Finance Working Paper Series, HF-009. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. July. Schill, Michael, and Susan Wachter. (1994). “Borrower and Neighborhood Racial and Income Characteristics and Financial Institution Mortgage Application Screening.” Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 9: 223-239. Schill, Michael, and Susan Wachter. (1997). “A Tale of Two Cities: Lending Patterns in Philadelphia and Boston.” Housing Policy Debate. Tootell, Geoffrey M. B. (1996). “Redlining in Boston: Do Mortgage Lenders Discriminate Against Neighborhoods?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 111(4):1049-79. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Table 2 (a) Residential Segregation Indices for Metropolitan Areas, 1990.” Residential Segregation Detailed Tables. http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/housing/resseg/resseg2.html (17August 2000). Wachter, Susan M. “Price Revelation and Efficient Labor Markets.” (2003). Texas Law Review. Weicher, J.C. (1997). The Home Equity Lending Industry: Refinancing Mortgages for Borrowers with Impaired Credit. Indianapolis, Ind.: The Hudson Institute. Wienk, Ronald E. (1992). “Discrimination in Urban Credit Markets.” Housing Policy Debate 3(2). Wyly, Elvin K., and Steven R. Holloway. (2002). “The Disappearance of Race in Mortgage Lending.” Economic Geography 78(2):129-169. Zorn, Peter M. (1993). “The Impact of Mortgage Qualification Criteria on Households’ Housing Decisions: An Empirical Analysis Using Microeconomic Data.” Journal of Housing Economics 3(1): 51-75. 22 Authors Susan M. Wachter is Richard B. Worley Professor of Financial Management and Professor of Real Estate and Finance in the Real Estate Department at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. 23 Table 1 Summary Statistics: Sample Mean Values VARIABLE ATLANTA 2002 ATLANTA 1997 BALTIMORE 2002 BALTIMORE 1997 CHICAGO 2002 CHICAGO 1997 DALLAS 2002 DALLAS 1997 LOS ANGELES 2002 LOS ANGELES 1997 NEW YORK NEW YORK PHILADELCITY 2002 CITY 1997 PHIA 2002 PHILADELPHIA 1997 WHOLE SAMPLE 2002 WHOLE SAMPLE 1997 TRACT-LEVEL VARIABLES CAPRATE 0.00 0.00 0.01 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.01 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.00 0.01 MEDIAN FAMILY INCOME 71950 69281 57865 45609 64196 56063 72320 76056 60595 63828 64053 60759 49772 41648 63105 57817 PCT ASIAN 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.04 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.07 0.07 0.07 0.06 0.03 0.03 0.05 0.04 PCT COLLEGE 0.47 0.43 0.35 0.23 0.33 0.26 0.39 0.41 0.30 0.32 0.30 0.28 0.24 0.16 0.32 0.28 PCT BLACK 0.40 0.49 0.33 0.57 0.16 0.33 0.10 0.11 0.09 0.12 0.21 0.28 0.26 0.45 0.16 0.29 PCT HISPANIC 0.03 0.03 0.02 0.01 0.11 0.11 0.10 0.09 0.18 0.17 0.11 0.11 0.03 0.04 0.12 0.10 PCT RENTAL 0.47 0.45 0.39 0.41 0.40 0.42 0.35 0.34 0.42 0.43 0.50 0.53 0.35 0.34 0.42 0.43 PCT VHIGH RISK 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.18 0.16 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.18 0.18 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.18 0.17 0.18 PCT N_A RISK 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.18 0.17 0.18 0.16 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.16 0.16 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.17 BORROWER-LEVEL VARIABLES INCOME ($1000) 92.48 68.29 77.44 48.43 80.39 59.91 97.94 93.83 87.54 75.30 90.62 76.97 66.15 42.69 85.79 65.42 ASIAN 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.05 0.03 0.04 0.02 0.08 0.06 0.06 0.05 0.02 0.01 0.05 0.03 BLACK 0.21 0.34 0.15 0.40 0.11 0.24 0.05 0.06 0.05 0.11 0.14 0.15 0.11 0.27 0.09 0.20 HISPANIC 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.15 0.12 0.10 0.05 0.18 0.13 0.07 0.05 0.02 0.02 0.13 0.09 MISSING 0.22 0.17 0.28 0.22 0.13 0.14 0.18 0.10 0.24 0.16 0.31 0.29 0.35 0.29 0.22 0.19 SINGLE 0.73 0.67 0.66 0.63 0.52 0.49 0.51 0.43 0.56 0.49 0.63 0.56 0.64 0.59 0.56 0.52 SINGLE FEMALE 0.28 0.28 0.25 0.28 0.20 0.21 0.16 0.15 0.20 0.22 0.21 0.18 0.22 0.27 0.20 0.22 SINGLE MALE 0.45 0.39 0.41 0.35 0.32 0.28 0.35 0.28 0.35 0.26 0.41 0.38 0.42 0.32 0.36 0.30 SUBPRIME 0.15 0.39 0.15 0.52 0.12 0.32 0.14 0.13 0.13 0.27 0.18 0.36 0.19 0.45 0.14 0.33 NUMBER OF LOANS 9920 3403 8476 4816 95849 31612 32419 3293 110158 20923 56144 14113 16768 9423 329734 87583 Table 2a Loan-Level Logistic Regression Results for Refinance Loans: 1997 Variable ESTIMATE ATLANTA 1997 BALTIMORE 1997 CHICAGO 1997 DALLAS 1997 LOS NEW YORK PHILADELANGELES CITY 1997 PHIA 1997 1997 TRACT-LEVEL VARIABLES CAP RATE Coefficient 89.91 76.37 28.36 -8.46 14.23 -0.66 8.38 CAP RATE ProbChiSq 0.01 0.00 0.01 0.78 0.44 0.62 0.36 LNMFI Coefficient -0.49 -0.77 -0.14 0.02 -0.46 -0.45 -0.69 LNMFI ProbChiSq 0.04 0.00 0.11 0.96 0.00 0.00 0.00 PCT ASIAN Coefficient -3.67 1.51 0.68 -4.74 -0.48 0.83 2.44 PCT ASIAN ProbChiSq 0.14 0.56 0.12 0.10 0.12 0.02 0.00 PCT BLACK Coefficient 1.25 0.00 0.89 2.64 1.10 1.06 1.14 PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient 4.90 0.90 1.28 0.60 1.71 1.49 0.82 ProbChiSq 0.02 0.71 0.00 0.55 0.00 0.00 0.09 Coefficient 0.34 -0.72 -1.08 -1.15 -0.13 -1.28 0.85 ProbChiSq 0.65 0.14 0.00 0.15 0.66 0.00 0.02 Coefficient -0.19 0.18 0.02 -0.22 -0.17 -0.64 -0.52 ProbChiSq 0.57 0.55 0.87 0.67 0.28 0.00 0.05 Coefficient -12.31 5.86 2.42 -1.29 2.50 5.79 4.68 ProbChiSq 0.00 0.04 0.01 0.80 0.15 0.00 0.02 Coefficient 13.93 -6.15 -0.39 -0.12 1.98 4.06 0.77 ProbChiSq 0.00 0.01 0.68 0.98 0.20 0.00 0.71 PCT HISPANIC PCT HISPANIC PCT COLLEGE PCT COLLEGE PCT RENTALS PCT RENTALS PCT VHIGH RISK PCT VHIGH RISK PCT N_A RISK PCT N_A RISK BORROWER-LEVEL VARIABLES ASIAN Coefficient -1.73 -0.22 -0.15 -0.51 -0.41 -1.21 -1.02 ASIAN ProbChiSq 0.10 0.64 0.16 0.34 0.00 0.00 0.00 BLACK Coefficient 0.24 0.86 0.79 0.31 0.65 0.27 0.77 BLACK ProbChiSq 0.05 0.00 0.00 0.18 0.00 0.00 0.00 HISPANIC Coefficient -2.06 0.95 -0.17 -0.27 -0.06 -0.12 0.00 HISPANIC ProbChiSq 0.05 0.02 0.00 0.33 0.29 0.24 0.99 LN INCOME Coefficient -0.75 -0.62 -0.41 -0.57 -0.20 -0.92 -0.73 LN INCOME ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 MISSING Coefficient 1.34 1.45 1.10 0.99 1.44 1.54 1.42 MISSING ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient -0.08 -0.25 0.13 0.39 0.12 -0.19 -0.15 ProbChiSq 0.51 0.00 0.00 0.03 0.01 0.00 0.02 Coefficient 0.01 -0.30 0.16 0.64 0.02 0.03 0.29 ProbChiSq 0.94 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.60 0.59 0.00 C STATISTIC 0.83 0.77 0.78 0.79 0.75 0.84 0.80 MODEL CHI SQUARE 1157 1171 6718 503 3384 4896 2727 SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE MALE SINGLE MALE Table 2b Loan-Level Logistic Regression Results for Refinance Loans: 2002 Variable ESTIMATE ATLANTA 2002 BALTIMORE 2002 CHICAGO 2002 DALLAS 2002 LOS NEW YORK PHILADELANGELES CITY 2002 PHIA 2002 2002 TRACT-LEVEL VARIABLES CAP RATE Coefficient -22.27 -9.69 69.18 38.10 89.54 -0.39 22.45 CAP RATE ProbChiSq 0.36 0.61 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.68 0.02 LNMFI Coefficient -0.05 -0.39 -0.02 0.02 -0.17 -0.27 0.30 LNMFI ProbChiSq 0.78 0.09 0.75 0.89 0.02 0.00 0.05 PCT ASIAN Coefficient -1.15 6.88 0.19 -0.86 0.48 -0.47 0.49 PCT ASIAN ProbChiSq 0.65 0.00 0.54 0.32 0.00 0.03 0.48 PCT BLACK Coefficient 1.22 0.61 1.14 1.54 1.08 1.00 1.27 PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient 3.88 -3.55 1.60 1.79 0.73 1.43 0.99 ProbChiSq 0.02 0.11 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.05 Coefficient -1.95 -1.98 -2.08 -1.83 -2.09 -3.16 -1.16 ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 PCT HISPANIC PCT HISPANIC PCT COLLEGE PCT COLLEGE PCT RENTALS PCT RENTALS PCT VHIGH RISK PCT VHIGH RISK PCT N_A RISK PCT N_A RISK Coefficient -0.54 -1.08 0.03 -0.46 -0.09 -0.68 -0.03 ProbChiSq 0.03 0.00 0.78 0.00 0.34 0.00 0.90 Coefficient -3.11 3.38 1.34 -0.56 0.79 2.81 -1.81 ProbChiSq 0.25 0.29 0.07 0.72 0.42 0.00 0.31 Coefficient 0.72 -3.79 -0.10 2.94 1.07 0.92 1.29 ProbChiSq 0.73 0.14 0.89 0.04 0.21 0.20 0.46 BORROWER-LEVEL VARIABLES ASIAN Coefficient -0.35 0.25 -0.01 -0.60 0.07 -0.56 -0.41 ASIAN ProbChiSq 0.46 0.58 0.91 0.00 0.06 0.00 0.03 BLACK Coefficient 0.84 0.46 1.08 1.02 0.79 0.45 0.21 BLACK ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.01 HISPANIC Coefficient 0.39 0.70 0.63 -0.37 0.33 0.38 -0.27 HISPANIC ProbChiSq 0.25 0.04 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.09 LN INCOME Coefficient -0.50 -0.57 -0.31 -0.54 0.03 -0.23 -0.44 LN INCOME ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.14 0.00 0.00 MISSING Coefficient 1.09 1.20 1.04 0.96 0.15 0.80 0.39 MISSING ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient -0.01 0.04 0.38 0.23 0.37 0.19 0.28 ProbChiSq 0.93 0.67 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient 0.18 0.24 0.40 0.16 0.18 -0.33 0.48 ProbChiSq SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE MALE SINGLE MALE 0.05 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 C STATISTIC 0.82 0.78 0.81 0.78 0.70 0.76 0.72 MODEL CHI SQUARE 1697 1115 13261 4652 6437 7071 1588 Table 2c Loan-Level Logistic Regression Results for Refinance Loans: 1999 Variable ESTIMATE ATLANTA 1999 BALTIMORE 1999 CHICAGO 1999 DALLAS 1999 LOS NEW YORK PHILADELANGELES CITY 1999 PHIA 1999 1999 TRACT-LEVEL VARIABLES CAP RATE Coefficient -29.49 26.95 41.78 22.90 17.40 -6.50 34.23 CAP RATE ProbChiSq 0.29 0.08 0.00 0.09 0.15 0.06 0.00 LNMFI Coefficient 0.18 -0.51 -0.21 -0.01 -0.49 -0.64 -0.73 0.00 0.00 LNMFI ProbChiSq 0.37 0.01 0.01 0.96 0.00 PCT ASIAN Coefficient 1.10 4.41 0.02 -2.83 -0.07 0.66 -0.10 PCT ASIAN ProbChiSq 0.60 0.05 0.96 0.02 0.77 0.01 0.89 PCT BLACK Coefficient 0.46 0.30 1.00 1.10 0.74 0.89 0.97 PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.09 0.03 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient 0.18 -0.80 1.17 0.64 0.82 0.99 0.24 ProbChiSq 0.92 0.69 0.00 0.14 0.00 0.00 0.56 Coefficient -2.51 -1.00 -0.83 -1.27 -0.60 -1.67 0.00 ProbChiSq 0.00 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.01 0.00 0.99 Coefficient -0.21 -0.28 0.15 -0.02 -0.48 -0.82 -0.56 ProbChiSq 0.45 0.29 0.12 0.93 0.00 0.00 0.02 Coefficient 2.17 -1.83 2.93 -1.12 0.05 3.92 2.88 ProbChiSq 0.47 0.44 0.00 0.63 0.97 0.00 0.11 Coefficient 6.03 2.03 2.13 2.84 2.77 2.20 1.38 ProbChiSq 0.01 0.35 0.01 0.20 0.02 0.02 0.46 PCT HISPANIC PCT HISPANIC PCT COLLEGE PCT COLLEGE PCT RENTALS PCT RENTALS PCT VHIGH RISK PCT VHIGH RISK PCT N_A RISK PCT N_A RISK BORROWER-LEVEL VARIABLES ASIAN Coefficient 0.34 1.03 0.06 -0.56 -0.10 -0.75 -0.21 ASIAN ProbChiSq 0.51 0.00 0.53 0.03 0.09 0.00 0.32 BLACK Coefficient 0.83 0.81 0.93 1.06 0.79 0.65 0.73 BLACK ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 HISPANIC Coefficient 0.52 0.38 -0.06 -0.22 0.04 0.23 0.09 HISPANIC ProbChiSq 0.19 0.22 0.19 0.03 0.36 0.00 0.56 LN INCOME Coefficient -0.55 -0.78 -0.52 -0.82 0.03 -0.78 -0.77 LN INCOME ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.29 0.00 0.00 MISSING Coefficient 1.88 1.45 1.27 1.17 0.92 1.67 1.32 MISSING ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient -0.10 -0.14 0.19 -0.23 0.23 0.05 -0.15 ProbChiSq 0.33 0.07 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.29 0.02 Coefficient 0.01 -0.30 0.03 -0.30 0.05 -0.18 -0.45 ProbChiSq 0.90 0.00 0.38 0.00 0.14 0.00 0.00 C STATISTIC 0.83 0.76 0.80 0.79 0.68 0.82 0.81 MODEL CHI SQUARE 1662 1523 10980 2176 2728 7720 3749 SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE FEMALE SINGLE MALE SINGLE MALE Table 3a Loan-Level Logistic Regression Results for Refinance Loans: 1997 LOS NEW YORK PHILADELANGELES CITY 1997 PHIA 1997 1997 STAT ATLANTA 1997 BALTIMORE 1997 CHICAGO 1997 DALLAS 1997 ASIAN* PCT BLACK Coefficient -27.24 4.10 1.90 -7.91 -0.21 1.27 -0.16 ASIAN* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.87 0.05 0.00 0.48 0.82 0.17 0.89 Coefficient 610.27 -37.17 -12.68 -55.53 0.13 -1.70 33.80 ProbChiSq 0.89 0.28 0.09 0.17 0.99 0.86 0.19 ASIAN* PCT N_A RISK Coefficient 1036.06 2.92 -1.73 -4.52 1.13 9.21 -23.42 ASIAN* PCT N_A RISK ProbChiSq 0.87 0.91 0.81 0.93 0.87 0.38 0.21 BLACK* PCT BLACK Coefficient 0.09 -1.79 0.15 1.66 0.31 0.07 0.04 BLACK* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.82 0.00 0.22 0.01 0.20 0.73 0.87 Coefficient -14.68 3.39 0.00 -12.18 1.65 1.69 1.00 ProbChiSq 0.00 0.40 1.00 0.29 0.67 0.51 0.76 BLACK* PCT N_A RISK Coefficient 17.41 1.84 2.74 7.62 4.73 3.44 -2.47 BLACK* PCT N_A RISK ProbChiSq 0.00 0.62 0.06 0.62 0.18 0.20 0.47 HISPANIC* PCT BLACK Coefficient 51.99 6.54 1.41 2.99 1.18 1.33 0.99 HISPANIC* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.76 0.06 0.00 0.02 0.00 0.00 0.12 Coefficient -556.38 -115.54 1.96 -6.31 -5.84 -0.62 -7.69 ProbChiSq 0.85 0.13 0.50 0.74 0.16 0.91 0.47 Coefficient -425.43 59.03 -1.65 -28.26 -3.06 4.27 -13.72 ProbChiSq 0.89 0.20 0.55 0.12 0.39 0.40 0.18 MISSING* PCT BLACK Coefficient 1.43 0.64 0.54 2.24 1.31 1.29 1.25 MISSING* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.00 0.03 0.00 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient -6.73 5.94 -1.28 -6.30 4.66 9.09 4.43 ProbChiSq 0.35 0.32 0.55 0.54 0.19 0.00 0.22 Coefficient 10.96 -17.09 -1.99 -1.91 3.36 4.24 -1.87 ProbChiSq 0.13 0.00 0.33 0.84 0.29 0.09 0.59 OTHER* PCT BLACK Coefficient 2.45 0.62 1.76 3.51 1.96 0.92 1.43 OTHER* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.00 0.02 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient -10.97 10.57 7.58 5.92 5.15 7.70 10.06 ProbChiSq 0.05 0.05 0.00 0.37 0.04 0.00 0.01 OTHER* PCT N_A RISK Coefficient 9.91 -7.95 1.29 3.68 2.28 4.60 7.83 OTHER* PCT N_A RISK ProbChiSq 0.04 0.05 0.43 0.55 0.31 0.05 0.01 C STATISTIC 0.83 0.78 0.78 0.80 0.75 0.84 0.80 MODEL CHI SQUARE 1216 1284 7056 528 3444 4956 2818 Variable INTERACTION TERMS ASIAN* PCT VHIGH RISK ASIAN* PCT VHIGH RISK BLACK* PCT VHIGH RISK BLACK* PCT VHIGH RISK HISPANIC* PCT VHIGH RISK HISPANIC* PCT VHIGH RISK HISPANIC* PCT N_A RISK HISPANIC* PCT N_A RISK MISSING* PCT VHIGH RISK MISSING* PCT VHIGH RISK MISSING* PCT N_A RISK MISSING* PCT N_A RISK OTHER* PCT VHIGH RISK OTHER* PCT VHIGH RISK Table 3b Loan-Level Logistic Regression Results for Refinance Loans: 2002 LOS NEW YORK PHILADELANGELES CITY 2002 PHIA 2002 2002 STAT ATLANTA 2002 BALTIMORE 2002 CHICAGO 2002 DALLAS 2002 ASIAN* PCT BLACK Coefficient 6.89 -1.51 1.96 -0.89 0.68 1.37 1.12 ASIAN* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.01 0.52 0.00 0.53 0.10 0.00 0.16 Coefficient -87.63 -23.85 -1.82 1.87 -0.80 5.38 0.40 ProbChiSq 0.04 0.53 0.73 0.88 0.80 0.21 0.98 ASIAN* PCT N_A RISK Coefficient -10.50 54.47 -6.52 -16.94 1.68 -1.97 28.04 ASIAN* PCT N_A RISK ProbChiSq 0.77 0.17 0.19 0.10 0.57 0.63 0.05 BLACK* PCT BLACK Coefficient 0.00 -0.44 0.46 1.08 0.51 0.35 0.41 BLACK* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 1.00 0.20 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.08 Coefficient 3.81 -6.37 -1.58 -4.32 -4.50 2.45 -3.05 ProbChiSq 0.34 0.31 0.23 0.27 0.10 0.07 0.46 Coefficient 4.12 -3.80 3.21 3.08 3.24 -0.77 3.52 BLACK* PCT N_A RISK ProbChiSq 0.21 0.45 0.01 0.48 0.20 0.54 0.38 HISPANIC* PCT BLACK HISPANIC* PCT BLACK HISPANIC* PCT VHIGH RISK HISPANIC* PCT VHIGH RISK HISPANIC* PCT N_A RISK HISPANIC* PCT N_A RISK Coefficient -0.20 0.17 1.18 1.51 0.79 1.16 1.76 ProbChiSq 0.90 0.91 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.01 Coefficient 33.08 -1.55 0.25 -12.39 -1.33 0.10 7.45 ProbChiSq 0.29 0.96 0.88 0.00 0.46 0.97 0.49 Coefficient 5.14 18.68 0.78 -10.02 -5.28 -0.45 -28.45 ProbChiSq 0.73 0.53 0.63 0.01 0.00 0.85 0.00 MISSING* PCT BLACK Coefficient 2.04 0.97 1.36 1.69 1.25 1.12 1.42 MISSING* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient -3.22 10.92 2.54 11.80 4.72 1.69 -3.50 ProbChiSq 0.50 0.02 0.14 0.00 0.02 0.18 0.19 Coefficient -6.74 -6.76 0.75 14.32 3.91 2.69 0.94 ProbChiSq 0.09 0.08 0.65 0.00 0.02 0.03 0.71 OTHER* PCT BLACK Coefficient 1.34 0.45 1.55 1.76 1.95 1.03 1.36 OTHER* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.00 0.11 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient -9.05 1.86 3.42 -1.51 2.66 5.47 -0.55 ProbChiSq 0.04 0.74 0.03 0.51 0.10 0.00 0.85 Coefficient 2.17 -0.74 -3.18 2.49 3.16 2.44 2.24 ProbChiSq 0.56 0.87 0.02 0.22 0.02 0.09 0.40 C STATISTIC 0.82 0.78 0.81 0.78 0.70 0.76 0.72 MODEL CHI SQUARE 1742 1175 13434 4782 6620 7142 1627 Variable INTERACTION TERMS ASIAN* PCT VHIGH RISK ASIAN* PCT VHIGH RISK BLACK* PCT VHIGH RISK BLACK* PCT VHIGH RISK BLACK* PCT N_A RISK MISSING* PCT VHIGH RISK MISSING* PCT VHIGH RISK MISSING* PCT N_A RISK MISSING* PCT N_A RISK OTHER* PCT VHIGH RISK OTHER* PCT VHIGH RISK OTHER* PCT N_A RISK OTHER* PCT N_A RISK Table 3c Loan-Level Logistic Regression Results for Refinance Loans: 1999 LOS NEW YORK PHILADELANGELES CITY 1999 PHIA 1999 1999 STAT ATLANTA 1999 BALTIMORE 1999 CHICAGO 1999 DALLAS 1999 ASIAN* PCT BLACK Coefficient 0.60 0.27 1.17 4.39 1.47 2.48 2.28 ASIAN* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.80 0.82 0.04 0.06 0.00 0.00 0.01 Coefficient -15.81 35.10 -0.89 -59.57 -1.77 8.88 -13.26 ProbChiSq 0.63 0.26 0.90 0.03 0.72 0.16 0.51 ASIAN* PCT N_A RISK Coefficient 49.08 -27.25 -12.60 21.22 -6.52 -7.09 13.83 ASIAN* PCT N_A RISK ProbChiSq 0.30 0.36 0.07 0.36 0.15 0.27 0.36 BLACK* PCT BLACK Coefficient -0.82 -0.59 0.39 0.81 0.11 0.59 -0.26 BLACK* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.02 0.02 0.00 0.01 0.55 0.00 0.23 Coefficient 5.28 -3.74 -1.06 -9.79 2.30 6.33 -1.98 ProbChiSq 0.21 0.28 0.41 0.05 0.48 0.00 0.57 BLACK* PCT N_A RISK Coefficient 6.93 5.53 4.91 12.41 3.45 0.38 4.06 BLACK* PCT N_A RISK ProbChiSq 0.06 0.09 0.00 0.05 0.26 0.81 0.25 HISPANIC* PCT BLACK Coefficient -0.29 2.76 1.03 0.25 0.21 0.82 2.18 HISPANIC* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.84 0.10 0.00 0.65 0.43 0.01 0.00 Coefficient -21.31 -42.76 4.58 1.69 -2.96 -1.08 4.11 ProbChiSq 0.42 0.31 0.05 0.79 0.34 0.76 0.71 Coefficient 44.94 31.59 -1.44 -3.90 -2.53 3.95 -12.85 ProbChiSq 0.13 0.31 0.54 0.49 0.35 0.25 0.16 MISSING* PCT BLACK Coefficient 0.82 1.14 1.18 1.29 0.69 1.08 1.21 MISSING* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.02 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Coefficient 2.48 -6.05 2.99 1.48 1.80 1.64 1.23 ProbChiSq 0.62 0.19 0.11 0.72 0.49 0.33 0.66 Coefficient 0.52 -4.93 0.34 -2.13 6.05 2.74 1.02 ProbChiSq 0.90 0.21 0.84 0.61 0.01 0.10 0.71 OTHER* PCT BLACK Estimate 1.92 -0.14 1.20 1.44 1.83 0.73 0.87 OTHER* PCT BLACK ProbChiSq 0.00 0.53 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Estimate -0.83 5.24 8.75 3.11 -0.45 4.99 10.68 ProbChiSq 0.88 0.25 0.00 0.36 0.83 0.01 0.00 OTHER* PCT N_A RISK Estimate 3.58 4.53 4.88 6.52 3.93 4.44 1.70 OTHER* PCT N_A RISK ProbChiSq 0.46 0.20 0.00 0.03 0.03 0.01 0.57 C STATISTIC 0.84 0.77 0.81 0.79 0.68 0.82 0.81 MODEL CHI SQUARE 1719 1579 11151 2203 2810 7755 3831 Variable INTERACTION TERMS ASIAN* PCT VHIGH RISK ASIAN* PCT VHIGH RISK BLACK* PCT VHIGH RISK BLACK* PCT VHIGH RISK HISPANIC* PCT VHIGH RISK HISPANIC* PCT VHIGH RISK HISPANIC* PCT N_A RISK HISPANIC* PCT N_A RISK MISSING* PCT VHIGH RISK MISSING* PCT VHIGH RISK MISSING* PCT N_A RISK MISSING* PCT N_A RISK OTHER* PCT VHIGH RISK OTHER* PCT VHIGH RISK