Document 11530606

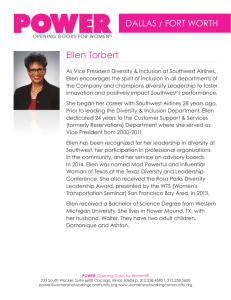

advertisement