AN ASTRACT OF THE THESIS OF

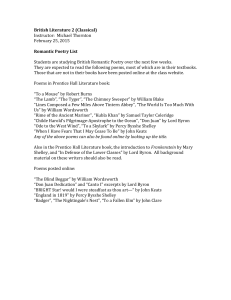

advertisement