Document 11530589

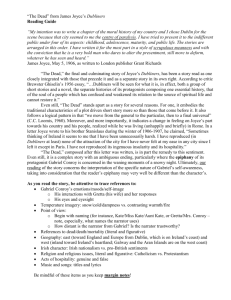

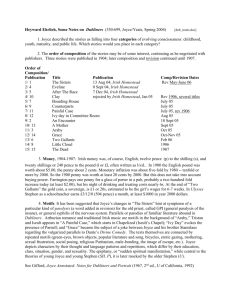

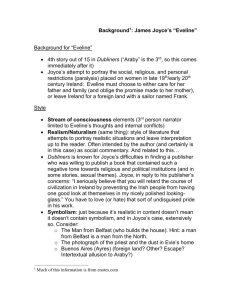

advertisement