Document 11530571

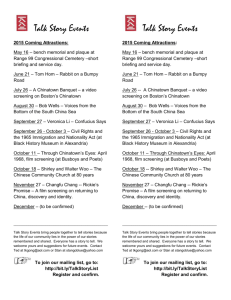

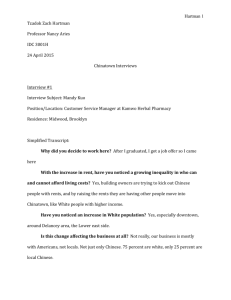

advertisement