Document 11530568

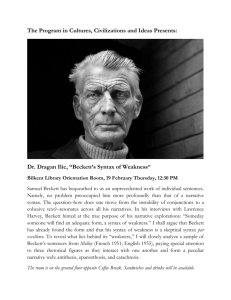

advertisement