Subordinated Rolling Equity: Georgette C. Poindexter

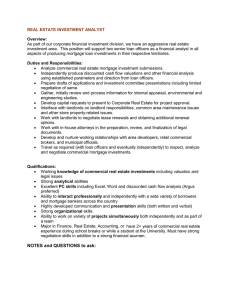

advertisement