DETERMINANTS OF COMMERCIAL MORTGAGE CHOICE

advertisement

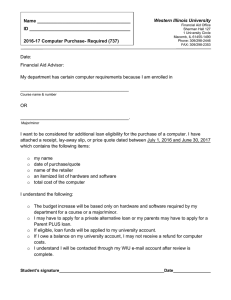

DETERMINANTS OF COMMERCIAL MORTGAGE CHOICE by Timothy J. Riddiough Working Paper #385 10/24/01 There are many differences between conduit and traditional whole loans that affect the welfare of the borrower. Some of these differences, such as loan rate differentials, are easily observed at the time a decision is required, while others, such as how will financial distress problems be resolved, are less easy to assess. It is useful to place mortgage choice in the context of the loan origination and production process. The fundamental distinction between conduit and whole loans in terms of the production process is that in conduit lending, financial service functions are unbundled and addressed by specialists, whereas whole loan providers act as generalists providing a bundle of financial services to borrowers. The cash flow in the conduit loan origination and securitization process is illustrated in Figure 1. Commercial real estate borrowers and security investors are endpoints in the loan production process. Commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) are often publicly registered and sold through traditional bond distribution channels to a variety of investors, who are typically unknown to the borrower. These securities are customized, in the sense that pools of whole loan cash flows are carved up and sold to investors who have demands for particular security characteristics. 1 The conduit loan originator merely provides mortgage underwriting services, and is paid a fee for loan origination. The conduit/security underwriter—who often directly coordinates a network of loan originators—pools the loans and determines appropriate cash flow allocations for the securities created from the loan pool. The underwriter earns the spread between the weighted average mortgage yield on a pool loans and the weighted average securities yield. Rating agencies earn fees for determining subordination levels needed to secure particular credit quality ratings and for monitoring post-issuance asset pool performance. These fees are paid by the underwriter, since freerider problems prevent fees from being directly passed onto investors. Rating agencies control security design and monitoring, but do not take investment positions in the securities themselves. In contrast, the whole loan originating lender/investor bundles together and provides loan origination, loan servicing, risk management and investment services. Whole loans have traditionally been made by life insurance companies and commercial banks. Although these lenders tend to be stable, they are prone to alternating periods of credit oversupply (possibly due to regulatory effects or competitive herd instincts) followed by credit rationing designed to address loan performance problems. Public market (securitized) capital providers are somewhat less prone to boom-and-bust patterns of this type—there are more investment options and fewer principal-agent problems— and are more apt to price capital in a “memoryless” fashion. However, public market debt pricing is more volatile in the short-run. This limits the conduit lender’s ability to commit capital, although the recent introduction of cash flow swapping mechanisms and the use 2 of swap spreads to benchmark CMBS yields have helped ameliorate the forward commitment problem. Figure 1 THE CONDUIT LOAN PRODUCTION AND SECURITIZATION PROCESS Loan Funding Asset Pooling Issuance Loan Payments Loan Payments Proceeds Loan Payments Borrower Conduit Lender (Servicer) Conduit/Security Underwriter Security Investor Ratings Monitoring Rating Agency 3 For the securitization process to be economically feasible, there must be specialization and scale economies that are achievable through the unbundling of financial services. This is because the costs associated with securitization are high: each participant in the process must be compensated separately, and increased specialization introduces costly information communication problems and potential conflicts of interest between participants. Given the basic differences between the conduit and whole loan production processes and funding sources, important distinctions emerge that are relevant to borrowers when deciding between mortgage sources. On the loan production side of the conduit business, standardization is essential to minimize production costs. Standardization is achieved by constructing generic, “one size fits all” loan documents, and by enforcing information gathering and monitoring standards so that underwriting decisions can be automated and communication costs between the intermediaries can be reduced. Efficient communication between the specialized intermediaries is especially important for conduit loans to be competitively priced. For example, the seamless provision of credit risk information from loan originators to security underwriter to CMBS investor is required in the conduit loan production process to ensure efficient pricing and liquidity. The following characteristics typify conduit lending: a more volatile pricing of funds; a more stable long-run availability of funding; an anonymous business relationship; standardized mortgage documents; and, increased disclosure requirements. 4 Closer borrower-lender relations, short-run loan price stability, contracting flexibility and less information sharing among third parties typify whole loans. These characteristics are likely to be important to the following types of borrowers: relative newcomers to the commercial real estate investment business with a shorter borrowing track record; investors in properties with idiosyncratic characteristics that require specialized contracting; and, higher risk borrowers. Paradoxically, larger commercial banks and insurance companies are typically not interested in lending to such borrowers (although many smaller local banks do so). Size and greater geographic reach create concerns as to asset quality, thereby increasing lender demand for moderate and large loan sizes backed by stable, relatively generic properties in diversified property markets. This implies that “B-quality” borrowers (in terms of track record, collateral quality and overall risk) are often constrained in terms of mortgage choice. Although their characteristics suggest a preference for whole loans over conduit loans, many whole loan providers will simply not deal with them. This forces such borrowers to choose conduit loans for which prices and terms are posted in a “take it or leave it” fashion. Conversely, “A-quality” borrowers, who in many ways seem best suited for conduit loans, are often aggressively pursued by larger whole lenders who are eager to own “investment grade” commercial mortgages. As a result, whole loan providers are often the low-cost source of finance in the A-quality market, whereas conduits cater to the B-quality loan market in which borrower mortgage choice is restricted. VARIANCE BETWEEN CONDUIT AND WHOLE LOANS 5 What follows is a more detailed, empirically based analysis of conduit versus whole loan programs. It is based on information on conduit and whole loan programs acquired via the Internet. This sampling method may result in some selection bias, as not all lenders have websites and the amount and quality of information on established websites vary significantly. Data was obtained on 39 conduit loan and 34 whole loan programs. In general, information for conduit loan programs was more extensive than for whole loan programs. Consequently, the sample was limited to 39 of the larger conduit lenders as listed in 1999 Commercial Mortgage Directory (including GMAC Commercial Mortgage, GE Capital and Wells Fargo). In contrast, a more extensive search was required to obtain information on the 34 whole loan programs. Many of the whole lenders are regional and local commercial banks, S&L’s, and mortgage brokers, with only a few larger banks and insurance companies in the sample. A majority of conduit lenders are commercial banks, mortgage banks and commercial conduits. Mortgage banks and commercial conduits have no deposit base with which to easily retain loan ownership. Alternatively, many whole lenders are commercial banks and S&L’s, and have the financial capacity to originate and retain mortgage ownership. There are two important reasons that conduit lenders are more likely to operate nationally as opposed to locally, and to offer far more loan programs than whole lenders. First, conduit lending is transaction oriented as opposed to relationship oriented. To compensate for their inferior knowledge of borrower quality and local market conditions, conduit lenders use formalized program requirements; on the other hand, whole lenders have a local market presence and lever superior knowledge of borrowers and market conditions, thereby facilitating relationship building. Second, conduit lenders' broader 6 variety of loan programs cutting across geographical boundaries reflects a desire by security issuers and investors to diversify asset pools across property types and geography. Diversification incentives relate to the informational disadvantage of conduit lending, since loan specific information asymmetries induce discounts in the external asset value. Diversification partially ameliorates idiosyncratic risk when there is information-related uncertainty as to the current asset value (and future loan performance). Thus, diversification facilitates arm’s length conduit lending operations by being a substitute for local market knowledge. All surveyed lenders offer permanent loans. By comparison, approximately half of conduit lenders--and only about 12 percent of whole loan providers--offer mezzanine financing. Mezzanine loans are higher risk than standard permanent first mortgages, and thus are more difficult to justify to bank and insurance company regulators. These loans are better suited to securitization, as credit risk can be stripped and reassembled through financial engineering. Interestingly, the proportion of construction loan providers in the two loan sectors is approximately equal. Construction lending was once the exclusive domain of commercial banks, but our data suggest that times have changed. What is surprising is that construction loans are currently not highly securitized. This leads to the conjecture that conduit lenders, by either partnering with third-party portfolio lenders or by retaining ownership themselves, offer construction loans as a bundling tactic in which a permanent loan takeout is funneled into the conduit for securitization purposes. Over half of conduit lenders offer bridge loan financing, versus about a third for whole loan providers. It seems likely that bridge lending is part of a larger conduit 7 lending strategy tied to securitized permanent loan financing. Generally, a much higher percentage of conduit lenders offers a full menu of loan types (14 out of 39) than whole loan lenders (3 out of 34). As noted above, this seems to be part of a more aggressive marketing approach intended to acquire permanent loans for securitization purposes—as opposed to an attempt to establish longer-term business relations by offering a full range of financial products. The data indicate that, with the exception of healthcare and hotel/hospitality (both of which are exposed to large operating risks), there is little systematic difference between lender types--a large proportion of both conduit and whole lenders offer a wide range of property type loans. We believe that once the market matures and market shares stabilize, along with consolidation and brand name recognition, loan conduit specialization by property type will emerge. Thirty four office conduit lenders and 33 retail conduit lenders as well as 30 office whole loan lenders and 31 retail whole loan lenders are included in the sample. A number of lenders offer more than one program for any specific particular property type. Perhaps the most striking feature of the survey is that significantly more data are available for conduit loan programs than for whole loan programs: 62 percent of all fields in the survey results are populated for the conduit loan programs, whereas the percentage is only 34 percent for the whole loan programs. There are several reasons for this result. First, since conduit lending is transactional whereas whole lending is driven by relationships, posting detailed program information significantly reduces search costs in the conduit lending market. Conversely, whole loan providers, with locally-based lending arrangements and lower search needs, produce less publicly available loan information. 8 Second, standardized documents allow conduit lenders to be more precise about loan program details; whole lenders are less inclined to provide detailed information because of their greater discretion to make exceptions to loan underwriting guidelines and to customize loans. Third, because information and communication technology are critical to decentralized conduit lenders, creating a fully integrated web-based loan application program that can advertise products as well as capture and transmit information may be both revenue-enhancing and cost-reducing. Conduit loan information is not only more available it is also more standardized with less variability across programs. This underscores the fact that standardization is needed for efficient conduit loan programs. Fields that are densely populated for both conduit and whole loan programs in the survey are: loan size; fixed/floating rate; loan-to-value ratio (LTV); and debt service coverage (DSCR). Whole loan lenders are more likely to offer variable rate loans than are conduit lenders. This is because CMBS investors generally do not like to mix fixed and variable rate product in the loan pools, and because an active fixed-for-variable swap market exists for security-holders who prefer floating rates. In contrast, many whole lenders prefer variable rate loans for asset-liability matching purposes. There is a high degree of uniformity in maximum LTV and minimum DSCR ratios across loan programs, although some whole loan suppliers will underwrite riskier loans. This probably reflects greater whole loan lender flexibility and underwriting discretion, as well as the use of repeated lending relations to resolve credit risk related information problems. Loan pricing is obviously a key aspect of the loan. Although relatively sparse, the data indicate that loan spreads tend to be smaller for conduit loans than for whole loans. This finding is surprising, given that whole lenders often target the high quality end of the 9 commercial mortgage market. However, as noted earlier, many of the larger whole lenders who target the A-quality loan market do not have web sites. This suggests that smaller regional whole loan lenders in our sample may be targeting the B-quality loan market for riskier, more information intensive loans. The dearth of A-quality whole loan providers in the sample raises another crucial issue in commercial real estate lending: the role of mortgage brokers. Many commercial property owners employ brokers to search out the best source of debt. A mortgage broker’s ideal customer is one who owns a number of well located, larger A-quality properties, as these are the borrowers actively sought by the larger whole lenders with low cost money. Because information frictions are the lifeblood of brokers, and because brokers zealously protect their best customers, brokers will typically prefer to associate with lenders who do not freely share borrower and loan program information with third parties. Thus, in the context of strategic information exchange, certain whole loan lenders may intentionally not share term information in hopes of protecting relations with brokers and higher quality borrowers. To follow up on this point, we contacted several of the largest whole loan lenders in the sample to request pricing information. Not one of the lender responded by simply providing a range of loan rate spreads (as many conduit lenders do on their web site postings). In all cases the lender wanted to establish a “relationship” by soliciting additional background information about us and the prospective property. Another interesting difference between conduit and whole loan programs is the maximum loan maturity. In general, conduit loans provide longer loan maturities. There are two explanations for this finding. First, many whole loan lenders often have relatively 10 short-term liabilities they wish to match their assets against. Second, conduit-CMBS issuers prefer a variety of shorter and longer loan maturities in order to target the unique maturity/duration preferences of investors. The data suggest that prepayment penalties occur more frequently with conduit loans than with whole loans. These penalties are often in the form of a defeasance provision which requires that, if prepayment occurs, the borrower replace the loan with a low-risk bond (often a Treasury bond) with the same remaining maturity as the loan and at a yield that equals the contract rate of the loan. The use of deposits, escrows, and reserves to address credit risk is more commonplace with conduit lending than with whole loan lending. This reflects the substitution of formal risk management mechanisms for informal monitoring. An important competitive advantage of conduits has been the speed with which they close. Numerous conduit lenders advertise loan closings within 30-60 days. Conversely, whole loan lenders, who have traditionally been slower in completing the due diligence process, rarely post their time-to-closing. A major reason for this difference is that, by using standardized loan documentation and following well defined procedures, conduit lenders generally have to address few of the issues that slow down whole loan funding. Conversely, an important cost of whole loan customization is that the due diligence process often takes a relatively long time to complete in order to address unique contracting and collateral property circumstances. Conduit lenders are more likely to offer non-recourse, single purpose, entity loans. Securities that are carved out of pools of commercial mortgages are complex and therefore difficult for investors to analyze. One way to simplify the investment analysis is 11 to eliminate recourse to the borrower. Some conduit lenders use cross-collateralization, which reduces the need to have detailed information about the borrower’s financial condition, and reduces potential legal complexities that often accompany financial distress. Requiring the borrower to organize as a bankruptcy remote single-purpose entity for a particular loan transaction further reduces analytical and legal complexity. The use of these provisions is consistent with transactional lending, as the costs of acquiring borrower specific knowledge sufficient to make informed recourse risk assessments are high for one-off transactions. Conversely, relationship lending is all about bilateral information sharing, which increases flexibility and lowers customized contracting costs. CONCLUSIONS An important dimension of securitization is the need to efficiently collect and disperse information among market participants. Advances in information technology (IT) therefore impact mortgage choice over time. Indeed, advances in IT are partially responsible for the recent explosion in securitization. The availability of higher quality-and lower cost--information is expected to result in greater liquidity and higher secondary market security prices. This will increase security issuance prices and lower borrower costs, resulting in a more competitive conduit-CMBS market. To illustrate the consequences that IT may bring to the marketplace, consider the role of the commercial mortgage broker. Mortgage brokers have traditionally provided a bundle of services, including the provision of market information, matchmaking between borrower and lender, and transaction facilitation by coordinating loan closing and 12 negotiation services among disparate parties. Information provision is the raison d'être of the Internet, suggesting that the traditional broker functions of market information provision and matchmaking can be efficiently accomplished by IT. Alternatively, other functions that require direct human intervention such as coordinating activities and residual negotiation services are more efficiently executed by a broker. Generic loans with low service intensity can be intermediated via the Internet, whereas customized and high-service intensity debt will require more traditional brokerage. This split has interesting implications for intermediation as it relates to loan quality. In the short term, traditional brokers will attempt to isolate their higher quality borrowers from the effects of disintermediation, while low quality borrowers will gravitate to the Internet. However, the fact that higher quality borrowers require lower service needs suggests that the Internet may eventually erode barriers created by brokers. This would result in fewer brokers working more efficiently with a larger number of borrowers. Consequently, deep as opposed to broad service provision is the likely result of advancing IT and Internet-based transactions. [Endnote: Koichiro Taira provided research assistance, and George Green commented on the work. This research was funded by NAR as part of their Transact 2000 program.] [Author bio: Timothy J. Riddiough (tjriddi@mit.edu) is the Edward H. and Joyce Linde Associate Professor of Real Estate Finance at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has served on the boards of OCWEN Asset Investment Corporation, the Massachusetts State College Building Authority, and the Real Estate Research Institute. 13 14