Todd Sinai The Wharton School University of Pennsylvania

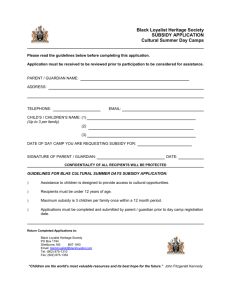

advertisement