Looking Back to Look Forward:

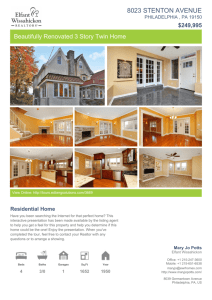

advertisement