An Urban Slice of Apple Pie Georgette Chapman Phillips*

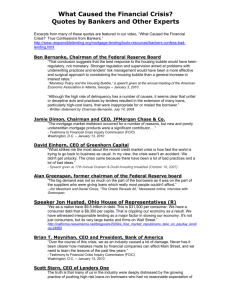

advertisement