Working papers in Information Systems MOBILE TELEPHONY

advertisement

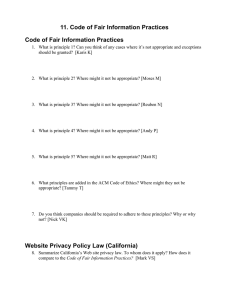

Working papers in Information Systems PRIVACY MANAGEMENT FOR NEXT GENERATION MOBILE TELEPHONY Steinar Kristoffersen WP 8/2005 Copyright © with the author(s). The content of this material is to be considered preliminary and are not to be quoted without the author(s)'s permission. Information Systems group University of Oslo Gaustadalléen 23 P.O.Box 1080 Blindern N-0316 Oslo Norway http://www.ifi.uio.no/~systemarbeid Kristoffersen Copyright © with the author(s). The content of this material is to be considered preliminary and are not to be quoted without the author(s)'s permission. Privacy management for next generation mobile telephony Steinar Kristoffersen Dept. of informatics University of Oslo P.O. Box 1080 Blindern 0316 Oslo Norway <steinkri@ifi.uio.no> +47 2284 2409 (phone) +47 2285 2401 (fax) Abstract: This paper is concerned with privacy management in settings where mobile telephones with Dictaphones and cameras are becoming commonplace. Such phones have been banned in several places, due to privacy concerns. Increasingly restrictive personal data legislations coming from, e.g., the EU Commission indicates that this is not simply an instinctive response to unknown technology and “Orwellian” scenarios. However, prohibition also rules out many productive and enjoyable applications of next generation mobile telephony in these settings. Therefore, an alternative and much more nuanced set of schemes should be explored, and that is the scope of this paper. It looks at the much richer ideas of awareness, privacy and control of objects in a shared space that is coming from Computer-Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) and contrasts them to the available mechanisms for privacy management in mobile telephony. The result is a new model for privacy management that may be used to implement a higher level of personal control with the increasing and potentially sensitive information flow caused by ubiquitous multimedia in next generation mobile telephony. Citation: http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen 1. Introduction The Scottish Secondary Teachers’ Association last year called on all local authorities in Scotland to issue clear instructions banning the use of mobile phone cameras within schools1. There are other examples as well, where mobile phones with cameras are seen to represent a huge risk to the personal safety of pupils and staff and to the human rights of the individual to privacy2. The foundation of the argument is that there is such as thing as a natural right to privacy3, which for instance comprises the control over the use of images. Mobile telephones, then, are a threat to that right. This is not simply a matter of badly conceived technology “creating” an opportunity for malicious behaviour. There is a wider set of issues at stake, and this is reflected by the European Union by the relatively recent Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC. Governments see themselves as having to control the flow of information in society, on the notion that privacy will not be sufficiently well managed otherwise. The paper is motivated by this “knee-jerk” response by governing bodies to the alleged privacy threats brought on by data communication, multimedia and mobile telephony converging. It explores existing ideas of privacy management from various domains, predominantly CSCW (Computer Supported Co-operative Work) and Computer Ethics. The objective of this paper is to elicit from that some core concepts and, eventually, a model that can improve the realisation of privacy management in next generation mobile systems. The wider goal of the research presented here is to discern, reason about and evaluate privacy management models that afford a much more nuanced and liberal approach than prohibition by furnishing users with mechanisms to control the flow of personal and potentially sensitive information (even if it is captured with somebody else mobile phone). Mobile telephones are becoming universal. Average ownership in Europe is above 55% and Spain, Norway, Iceland and the Czech Republic are among the countries that have 1 http://www.ssta.org.uk/PressReleases/PressRelease_mobilephoneban.htm http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/wear/3390909.stm 3 In a neo-Lockean sense? 2 Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen more than 90% cell phone coverage in the population. Luxembourg, Taiwan, Italy and Hong Kong, to name a few, are above 100% 4 . At the same time, the technical functionality of mobile telephones is broadening. Most new models have digital highresolution cameras with zooming capabilities, as well a Dictaphone. Using Multimedia Messaging Services (MMS), data thus recorded can easily and widely be distributed. Mobile telephones are small and fashionable5 and they are waterproof, which means that they can inconspicuously be used in entirely new settings. There is, arguably, convergence of internet technologies and mobile telephony, which enriches the communication possibilities of such devices immensely (ITU Internet Reports 2002: Internet for a Mobile Generation 6 ). The problem is that using this technology, people can compile potentially compromising material about each other (or themselves) in an inconspicuous way. Still, the models that such devices implement in order to let the users manage their privacy, the projection of their activities upon others and (reciprocally) their awareness of others, are very crude indeed. You are either online, or you are offline. Most cellular phones have profiles which allow them to be roughly adapted to the specific use context, by adjusting ring volumes, activating vibration, etc. Moreover, one can usually create “ring groups” to which contacts may be assigned in order to get an audio cue as to who is calling. Many cellular networks are starting to offer the possibility of location-based services7, and for those users are usually required to request, accept and receive information across SMS (Simple Messaging Service) or WAP (Wireless Application Protocol). However, many complaints have been made about insufficient and unreliable privacy management associated with such services8. When others have been concerned with issues of privacy and mobile telephony, it has mainly been linked to positioning services (Barkuss and Dey 2003) or the intrusion of (loud) speakers of their private conversations if, indeed, that is what they are, on others 4 http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/at_glance/cellular03.pdf http://www.phonecontent.com/bm/news/nokia/7200.shtml 6 http://www.itu.int/osg/spu/publications/mobileinternet/ 7 http://www.wireless.expert-views.com/2005/02/nokia-launches-next-generation-platform-for-locationbased-services-in-gsm-and-wcdma-3g-networks/ 8 http://www.aftenposten.no/nyheter/nett/article387527.ece 5 Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen (Laurier 2001). Network snooping is considered in this paper as a technical challenge (on the network level) for operators, and, however important. It is therefore outside the scope of this paper which is concerned with users’ as well as non-users’ privacy management, its underlying models and philosophies and the services offered to them for that purpose. 2. Privacy in CSCW The work on privacy in CSCW is pertinent because many of the technologies that are now driving the convergence of mobile telephony and ubiquitous computing, have been central to that community (Boyle et al. 2000). CSCW has, moreover, seen its work on privacy underpinned by a fair amount of empirical work and testing (Hinckley, Ramos et al. 2004). This is not to say that it is from within CSCW that the most profound theoretical reflections on this topic are coming, nor is it a claim of this paper that the models of privacy and the implementation of such models in this area are unsurpassed by contributions from other fields. However, in CSCW it was acknowledged early that: “Increasingly, we are seeing such systems incorporate sensors such as microphones, cameras and signal receivers for wireless communication. These sensors have the potential to transmit information such as speech, video images, or signals from portable computing devices, active badges (…), and so on (Bellotti and Sellen 1993, p. 80)”. What was described and reasoned about as “ubiquitous computing” and CSCW then, is mobile telephony today. In a recent paper, Palen and Dourish (2003) set out claiming that “In an increasingly networked world, privacy-protection is an ever-present concern (ibid p. 129).” They state that privacy is such a broad concern that one needs improved conceptual models in order to reason analytically about it, and they state that “Privacy regulation is complicated and has a range of functions, from maintaining comfortable personal spaces to protecting personal data from surreptitious capture (ibid p. 129)”. Privacy, according to this model, is contingent and multi-faceted. Building on Irwin Altman, they outline a model comprising three boundaries: Disclosure, identity and time. Altman subscribes to a theory of privacy as restricting access to one’s self. Thus, the Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen model of privacy proposed by Palen and Dourish can be seen as the dynamic process of negotiating access to the personal sphere along these boundaries. The boundaries that constitute the core of Palen and Dourish’s model are implicitly assumed and even applied in previous work as well. For instance, Bellotti and Sellen (1993) argue that a framework for the design of privacy in ubiquitous computing environments is needed. The paper departs from an assumption (commonly made also in the domain of mobile phones with cameras, as was shown above) that computers can be put into insidious, unethical, malicious use. Information technology leads to increasing capture and storage of information about people and that raises serious concerns about the protection of privacy. Moreover, poor design results in invasive technology. Badly designed user interfaces make the technology intrusive. Thus, it can interfere with crucial social mechanisms and they claim that privacy challenges are brought to the fore by the ways in which technology attenuates feedback and control mechanisms. They say that “In attempting to design systems which reduce invasions of privacy, it would be useful to have a practical working definition of the concept (p. 78)”, but they do not offer one in the paper. However, Bellotti and Sellen propose a design framework that relies implicitly on an understanding of privacy similar to the model suggested by Palen and Dourish (op. cit). The design framework can therefore be seen as a manifest that describes privacy management for such environments. The framework can briefly be descried as a set of design questions asked (on behalf of a hypothetical user) about which information is gathered when, its distribution and usage. The crux of the design framework is that it explicitly states that this information should be fed back to the user and that the user should act on these grounds to exert control over exactly those factors. So, similarly to Palen and Dourish, Bellotti and Sellen proposes a model based on contingent negotiation of access to information, and validation of the purposes of its use. They are, however, not concerned with the boundaries of self versus other, at least not explicitly, so correctness of representation is not an issue here. Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen Paul Dourish (1993) has also looked at matters relating to privacy in an entirely different context, namely that of implementing a system to control the Media Space application of Xerox’s laboratory in Cambridge. Dourish describes a software package by which the system can be controlled by the actors. Interestingly, there is a lot of emphasis in the paper on the interplay between the transparency of the technical platform, i.e., “all” the users know how to configure the system themselves, and the cultural setting; which are “the social components which determine acceptable use and behaviour”. The paper emphasizes especially the flexible and dynamic control of the users with regards to who can access their personal sphere. So, quite narrowly, the system relies on an assumption of privacy as a matter of regulating access. Moreover, Dourish emphasize the importance of co-adaptation between the technology and the culture of the workplace in which it was used. The system, one must say, was a success in this context inasmuch as it was deployed and used over a number over years. There was no explicit sign-up to the technology, it was simply made available to new members of the lab. Of course, this also points in the direction of workplace culture and expectations stipulating “adoption” of technology. Richard Harper has described a related development effort from a slightly different point of view (Harper 1992). He found that adoption and use of technology, even in a situation where privacy potentially was very much at stake, was guided by organizational roles and job responsibilities, as the users perceived them. So, in one organization, users accepted the technology because they considered it their job to partake in experiments pertaining new technology, even though they were wary of the potential consequences. In another organization, people more openly recognized the need for the system, and seemed to make the trade-off that it would be beneficial to them, although they did recognize the challenges related to privacy “elsewhere”. The importance of company culture is quite easily illustrated with a reference to a similar infrastructure introduced on the workshop floor of production facilities in the UK and the Netherlands, a setting in which emphasis was with the practical adaptation and fitting of ’bad’ technology into good organization practices (Pagani and Mackay 1993). They Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen describe how engineers and designers recast the technology from a ‘videophone’ into a tool for technical inspection of the production line. Video was not adopted as an interpersonal communication medium, but voice was used instead. In an office share between two other groups of users in the same company, it did not particularly bother the users that the technology was unreliable and plagued by latency. It could for example show people in their offices long after they had left. Even so, it was described as “nice-tohave” and a medium that brought the two groups closer, with the “small” modification that it was simply not relied upon as a source of information. A lot of the work with privacy in CSCW has ended up concluding that privacy is social “through-and-through” and that most of the responsibility can be handed off to users, if they are granted sufficient control and understanding of the technology. A complementary design recommendation has often been that of reciprocity, in other words, when creating a system that might compromise privacy; one should make sure that it is mutual. It is normally a property of physical spaces that when someone else can see or hear you, then there’s a good chance that you will see and hear them (Fish et al. 1993). Hong et al. recognize that we all perceive privacy differently (Hong et al. 2004). They describe privacy as a design issue, similarly to Bellotti and Sellen (op. cit.). Also, implicitly, they subscribe to the model of privacy as contingent and relative, since they aim to provide designers with a model that can be implemented to offer a “reasonable level of privacy that is commensurate with the domain, with the community of users, and with the risks and benefits to all stakeholders in the intended system (Hong et al. 2004)”. There are some very interesting assumptions underpinning their work. They focus, explicitly, on privacy as a separate concern from system security, and claim that knowledge (of location, e.g.) is not in itself harmful to the “self”. It is the risk of being subjected to distress that the model is intended to prevent. Moreover, Hong et al. also see that risk is a trade-off between concerns, e.g., sometimes the greater society’s needs must rise above that of individuals (for instance when cars are required to carry license plates). The model that they propose consists of a serious of highly relevant questions that should be asked by designers when creating technical solutions that might obstruct users’ need Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen for privacy. There is in principle nothing that separates this model from those surveyed above. Albeit it does contain some new questions, they still pertain only to the trade-offs that have to be made when giving up a piece of information, the desire to need what is it used for and by whom, etc. There are a couple of new perspectives in this mode, for instance that it explicitly is concerned with the value proposition to the users that “give up their privacy” and, contrary to their conceptual groundwork they mix into it some elements pertaining to data security. Still, it has to be described as a contingent, relational model in which regulation of access through managing the risk of unwanted disclosure, the control of information dissemination through data security concerns and the verification of representation as part and parcel of the model asking questions about the quality of the information stored. Summarizing the point of view of some seminal contributions in CSCW privacy is fundamentally a derived phenomenon. It is treated, and to some extent with success, as a design issue, although of course this is quite an extreme stance compared e.g., to the stance of the European Commission. We find, like in Harpers work, that it is interpreted differently between different cultures (Harper 1992). Privacy, in this manifestation, makes and aims for the possibility to withdraw from exposure through access regulation. Consistently also, there is keen interest in furnishing control over personal information. It is in some sense treated as the subjects’ own property, a property of which they are entitled to exclusive control. Concern with the correctness of representation is not dealt with consistently in CSCW. Interestingly, CSCW has not picked up many other perspectives on privacy that have been discussed elsewhere in the literature, for instance in business ethics and philosophy. For instance, some see privacy as a derived implication from that of personal security, or the right of freedom from the judgement of others. These issues will be discussed again towards the end of the paper. Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen 3. Next generation mobile telephony We have already, pretty much everywhere, entered a world of online, omnipresent, multimedia recording devices. One need not speculate what the next generation of mobile telephony will be like exactly. Looking at reports from the industry (Ralph 2002; Harmer 2003), one can assume that it will be pretty much like we have already, only “better”, using: • Packet-switched network connections, potentially “always on” • Overweight on prizing per data volume, but some fixed prices services that would otherwise be much too expensive on an item-per-item basis • Simple- and Multimedia Messaging Service (SMS, MMS), for which the industry will primarily continue to develop machine-to-person services, i.e., ring tones, logos, animation and videos, eventually • The mobile phone is and will continue to be a high-resolution (video) camera with a Dictaphone, and these elements can be combined in messages or emails as well as in real-time video conferencing, and there will be • Location based services (based on network triangulation as well as GSM) • M-commerce, in which e-cash and credit card usage may leave tracks of consumer behavior, etc. Unfortunately, there is not much empirical research on the use of mobile telephony around: “While technological innovations in general have been the focus of a wealth f research, telephony, and more specifically mobile telephony, is only just beginning to be studied in any depth (Lacohée et al. 2003, p. 206). “ Taylor and Harper has written a nice “design-oriented sociology” of the ways in which young people use SMS on mobile phones to exchange “gifts” of value, such as emotive texts, jokes, graphics, etc (Taylor and Harper 2003). Privacy is not a concern of their paper; however, one can easily see the correlation to multimedia messages created combining photos of friends (or foes) with personalized messages (Berg, Alex et al. 2003), so the relevance is still clear. Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen In (Perry et al. 2001) there is a brief exploration of how mobile telephones where used by traveling workers to keep abreast with developments in the workplace whilst they were away. Their account shows that even businesspeople were using the mobile phone in an informal, preemptive fashion, to make open enquires even of a social nature, at the office. These calls were made on the discretion of the mobile user. This way of using the phone for updates of a “peripheral” nature corroborates with that of informal communication in CSCW (Fish et al. 1993). In CSCW, on the other hand, emphasis usually has been on serendipitous encounters (Bellotti and Bly 1996; Bergqvist et al. 1999; Edwards 1994) rather than the very formal establishing of sessions that can be found in mobile telephony (Cesare 2001, Yigal et al. 2000). Palen et al. looked at a small number of new mobile telephony users using interviews and “voice mail feedback” data from the users to find out how their phone practices evolved over a period of six weeks. They found that users quite rapidly modified their perception of the appropriateness of mobile telephony usage to different circumstances9, and that these device, clearly, were (considered) part of the socio-technical network (Palen et al. 2000). Palen et al. make the claim that privacy violation concerns have shifted from the nonusers’ infringement on the users private communication to the mobile speaker’s infringement upon the ears and thoughts of the non-users. It might be that some people would consider this a matter of “pollution” rather than privacy. One could, arguably, claim that the notion of privacy does not really apply to situation in which the disclosing party is not making a reasonable effort to protect it (McArthur 2001). One might, on the other hand, say that people sometimes do not know their own good, but even if they did, there are two parties in a phone conversation and the second party is indirectly exposed 9 This is something that most of us, perhaps, remember from our own “careers” as owners of a mobile phone: From skepticism and even prejudice about what people think they are and do when they insist on making their private calls a public concern, via superenthusiasm that makes us carry the phone around with us everywhere and then to some sort of organizationally or culturally co-adapted pattern of usage where one either is expected to answer a call in the middle of a meeting, or to turn it off from the beginning. Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen through such conduct. Still, one does see from this that the “non-user” of information that is communicated in a phone conversation is not the intended, voluntary recipient of the message. In CSCW, however, there are multiple receivers, all of which are intentionally “targeted” and the concern is usually not that they might “connect” inadvertently, but rather that the “communication” (and thus implicitly the “content”) might not be deliberate. The symbolic meaning of either the message or the device or the act of actually making a call might still be directed at a larger audience, of course, and this has been pointed to by, for instance, Rich Ling (1996). The act of impressing ones peers might have a bearing on how people manage their privacy. Also, Ling maintains that teenagers buy-in so strongly to mobile telephony because they are interested in being accessible to their peers. The telephone is used for micro-coordination (Ling 2001). In another report, Ling and Yttri (1999) use the term “hypercoordination” to include social and emotional aspects. SMS, for instance, is often “low in informational value but high in terms of social grooming (Lacohée et al. 2003, p. 206).” This paper disagrees with these interpretations of “co-ordination”. When people phone home to say that they are, in fact, on the bus on their way home, it is not because the information shall be used to do coordination work. It still is important, however, since “… it shapes the character of the ordinary geographical work that we need to do every time we are talking to people we know but we know not where (Laurier 2003). “ In other words, it is used to establish a communicative context that is otherwise, from landline telephony, implicitly known (Lacohée et al. 2003, p. 207). Palen et al. observed many different strategies for managing access, and, if privacy shall be interpreted as regulation of access to one’s personal sphere, then this is a relevant concern. Some subjects forwarded all calls to their mobile phone, some subjects kept their phones off all he time, and most subjects struggled with deciding whether to answer calls from blocked or unknown numbers. Some people limited the distribution of their Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen phone numbers (Palen et al. 2000). This is corroborated by another study of mobile telephony usage, in which as many as 70% said that they were restrictive about giving out their phone number. Even more surprising, perhaps, was that only 18% gave the number freely to their friends (Licoppe and Heurtin 2001, p. 100). Green et al. find that rather than being devices that transcend spheres and cross existing boundaries of private and public space, mobile devices are “space adjusting technologies”. This is quite similar to the ambitions that underlie CSCW research (Green et al. 2001). They make it worth noticing that “Both individually and in concert therefore, people develop strategies to maintain or reconstruct boundaries of public and private space (ibid p.149).” One way that that people are reconstructing space, is by actively acting as if conversation cannot be overheard, (Goffman 1963). There is probably a great difference in the extent to which that will work in the same way in a workplace setting compared to a public place. Goffman’s work is about behavior in public places, and one particular characteristic, almost the fundamental aspect, of public places is that they are arenas in which people can gather to exchange ideas, rather privately and in quite skillfully restricted settings. Think of the walk in the park, the pub or clubs of various orientations. These public “places” are not unrestricted. Family life, on the other hand, is private, as private as can be, but communication within that sphere is not at all qualified in the same way as exchanges in the public spaces. On the contrary, any topic can be brought up. Participation, however, is of course heavily restricted. Workplaces can be seen as a third, distinctive setting in which, again, separate conventions and practical arrangements govern membership, participation and communication. CSCW and ubiquitous computing have been concerned with this arena, an arena in which one cannot, generally, get away with pretending that no one can overhear a private conversation. Therefore, also, people tend to leave the meeting room to talk outside, even if there are more people on the outside than on the inside, and the meeting cannot go on anyway because the other participants are waiting for them to get back in. People are neither fundamentally lazy, nor rude. Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen Licoppe and Heurtin argue that mobile telephony is reciprocal. They found a correlation between the number of outgoing and incoming calls, and place this within the larger context of managing bi-directional social bonds. It is easy to agree with them when they assert that “Reciprocity does not occur only within the improvised regulation of sequences of telephone calls between two parties; it pervades a web of interactions through different channels (Licoppe and Heurtin 2001, p. 107).” One might then summarize the finding of modern mobile telephony usage, contrasted to that of ubiquitous computing in CSCW, as listed in the table below: Properties Information flow Aligned with space Location co-ordinates Communication Number of non-users Status of non-users Status of receivers Co-ordination level Reciprocality Technology transparency Session management Ubiquitous computing (CSCW) Pull Private Contextually-derived or à priori familiar One-to-many Few Dynamic Sometime anonymous Micro (at the core) Low High Serendipitous, continuous often symmetric Low Symbolic value of communication/devices Low Emotive and social weight of communication Access control transparency Low Mobile telephony Push Public Explicit One-to-one Many Static Never anonymous Macro (if at all) High Low Conscious, discrete, often asymmetric High High High Table 1: Some important properties of existing privacy models in CSCW and telephony It seems that in CSCW, particularly because the research into most of these technologies has been motivated by the desire to support peripheral and direct awareness as one important factor in informal communication, privacy models have been concerned with information that is pulled from the private subject. For mobile telephony, it is the other way around. That is to say, on a technological perspective, information is pushed. If the mobile phone is used as a camera to ‘spy’ on third-parties, however, the picture becomes Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen fuzzier, but that first step of “pulling information off” someone is still carried out by someone within the private sphere. CSCW is designed to work in the workplace, which is a private place compared to the global distribution of mobile telephony. Communication in CSCW has been, in terms of awareness information, going from one-to-many: Generally, CSCW-systems have been set-up to broadcast information. Mobile telephony, on the other hand goes from one handset to another. For many applications of 2.5 and 3G cellular networks (e.g., SMS, MMS) messages and pictures can, indeed, be sent to many receivers. This is, in the perspective of this paper, however, considered a local, application level facilitation of one-to-one communication. The network transmits them in a “serialized” fashion; it has no concept of a group. One interesting exception is the “buddy”-oriented location services and group-based chat-services that are becoming more widely available now, even in cellular network. These applications indicate some common ground even on the conceptual level between “groupware” and telephony. Moreover, they underpin clearly the hypothesis of this paper that lessons can be learnt from CSCW to mobile telephony and perhaps also that seamlessly integrating the functionally of these two domains will be a requirement. One must expect PC users to wish to chat with friends who are currently away from their desks, using the best technology available to them. CSCW has really not been much concerned with non-users, and if there are any, their status is dynamic inasmuch as much of the focus of these environments has been to make the transition from non-user to user easier (session management). This is inextricably linked to the point below, namely that it is used for micro-coordination. In mobile telephony this is always opposite. If you are in the loop, you are in the loop. The caller knows the “called“, and no-one else is supposed to eavesdrop. There are exceptions, but then act of communication in the fashion or parts of the communication itself has symbolic rather than substantial value. CSCW-systems are usually not fully reciprocal; instead one can perhaps say that they are asymmetric. In mobile telephony it is the other way around. There are other differences Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen as well. Sessions are usually managed in an implicit fashion by CSCW-systems and many of the experiments that have proven successful have exposed the underlying infrastructure to technologically skilled users. Communication content in CSCW has been work-oriented and co-ordination intense, but has carried very little emotive weight. With telephony it is the other way around. Much communication is low in information content, but high in social management (Ling 2001). Finally, a phone is off when it is off. Many CSCW systems are technically speaking always on, and “off” only when no-one are looking/listening. Therefore, one might actually argue that it is mobile telephony usage that is socially sanctioned, whilst CSCW continually tries to develop technological means for regulation; this is quite the opposite of what is sometimes claimed (Dourish 1993). 4. Revisiting privacy The notion of privacy as a relational (or more broadly speaking, contingent) and relative concept is common beyond the CSCW-community of course. Introne and Pouloudi (1999), coming from the Business Ethics community, share this view. Going further still, they maintain that privacy is essentially the freedom or immunity from the judgment of others and the right to critically examine the relationships to others in a particular context. They go on to make an argument that deeply shows the relationship between their position and that of the previous authors (and indeed the Directive 95/64/EC): They maintain that only the information about others that is relevant and appropriate to the particular (and appropriate) judgment, should be made available. This really only extends the argument of control into a extreme position, since it denies other members of society at least as fundamental rights as privacy, such as freedom of speech and thought and the exclusive right to their own mind. Moreover, Introne and Pouloudi suggest a principle of equal power, so that all stakeholders ought to have equal opportunity to successfully make a claim to privacy (ibid). One might say that this principle seems overly idealistic compared to the true state of the world. The stand of Hong et al, that was mentioned earlier (Hong et al 2004), on privacy as something entirely separate from system security is very different from that of Thompson Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen (2001). Thomson argues that some issues often associated with privacy is better analyzed in quite different terms, namely that of personal security (ibid). The risk at stake then is not that private information might get known, but that others might threaten the security of the originator. Confidentiality, for instance, is something often “lumped” into the concept of privacy. It should, according to Thompson, instead be seen as a “managerial” responsibility; a contractual response to the request for an exchange. It is within this perspective that the first sketch of an “integrity-preserving model of privacy” fits. It is possible to model the “multimedia capture and send” aspect of mobile telephony applications such as MMS, quite neatly using a simple state chart, thus getting ready to launch more elaborate and integrated models later: capt 4 send 1 send end capt 2 store 0 3 store item 5 item empty Figure 1: A model of mobile telephony "capture and send" applications Rather informally, still, Figure 1 shows how such applications start from a state (number 0) from which the users decides to capture something using, e.g., the Dictaphone or vide/camera of the mobile phone. The phone is a “black box” which responds with issuing the capt action. The user (with a device now in state 2), can analogously either store or send the content (multiple times, if desired, in alternating sequence) before concluding with an end-command. Alternatively, from state 0 (the start state), the user Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen can go to the multimedia storage of the device and perform the same actions reusing existing objects. The mode matches some of the aspects pointed to in Table 1 inasmuch as the information is pushed, it makes no reference to the spatial context of use and therefore it can be seen as embedded in a fully public space. Communication is one-to-one, potentially (and manually) one-to-many in the limited fashion explained above and the receivers are explicitly known (although this is not easy to see in the model, yet, at this high conceptual level, they have to be “picked” in order for the sender to “send”). Location information sharing could be modelled analogously to multimedia capture. Sessions are seen as highly discrete, even discontinuous and asymmetric (the senders can go on with their business irrespective of acknowledgement of receipt). Similarly, a (typical) CSCW application with “capture and send” functionality can be drawn as a state chart, showing how the “same time - different place10” category can be modelled. It is not the aspiration of this paper to say that the two models are comparable or that they ought to be more or less different than what they are. The aim is to start reasoning more precisely about exactly which properties such privacy management models have (or ought to have). 10 http://www.cc.gatech.edu/fac/Gregory.Abowd/hci-resources/area-bok/cscw.html Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen check_send 1 4’ send_ok capt capt_ok 4 send no_send check_capt send 1’ 2 capt item no_capt store 0 end check_store store no_store 3 store_ok 3’ 5 item empty Figure 2: The "CSCW extension" to the “capture and send” model In this model, each operation is preceded by the application looking up if the intended operation e.g., capture), is allowed, given a set of criteria and potentially known stakeholders not visible in the diagram on this level of detail. Information can be “pulled”, due the combination of the “same-time-different place” type of application and the “check_cap” (e.g.) action. Still, there is a lot of functionality missing from the model, e.g., the notion of context and the status of non-users. Co-ordination is still (in terms of applications- and thus privacy management) taking place on a macro level. Not all aspects of privacy management in the two pertinent domains have been included, yet. Reciprocity is one aspect of privacy that is perhaps overrated (which in future research pertaining to this paper will be considered an empirical question) and might even be misguided (a theoretical concern, potentially). Hudson and Smith (1996) present a nice argument in which they point to the problems of reciprocity forcing all spaces to become public spaces, all events becoming equally important and therefore, whilst purporting to represent a property of face-to-face encounters in physical spaces it really implements some rather disruptive anomalies that were never really part of the physical word. For instance, if someone enters a large room then that experience in itself consumes all of the Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen attention of person entering (presumably), but might and should go largely unnoticed by most of the people already in the room. A digital environment cannot really represent such analogue qualities very well, regardless; however, the abstract model of session- of privacy management ought to be able to capture such properties. For this purpose, the models above will have to be extended in future research. 5. Conclusion This paper has shown that the ideas coming out of CSCW with regard to privacy are probably not instantaneously useful with regard to resolving the challenges imposed on us by networked mobile telephones with cameras and Dictaphones. To begin with, they are very different, and much work remains to reconcile the underlying models of privacy management. This will be pursued in future work. One working hypothesis of this paper, that CSCW can be seen as a constitutive factor of modern mobile telephony and therefore would offer particularly useful lessons for that domain, remains promising, but “to be proved”. This work might also become useful inasmuch as it can test whether omnipresent multimedia devices of 3G telephony, that so clearly carry with them technological components that are similar or even exactly the same as those from within CSCW, are really the products of such a convergence after all. This paper has pointed to quite longitudinal practical experiments with technology that potentially could compromise the privacy of its users. It is a strong indication that privacy is foremost a pragmatic, contingent and dynamic value when its success or failure depends so much on the culture of the setting and the practical circumstances, and is negotiated within those terms. That would also explain how similar groups produce different results upon encountering the same technology (Kraut et al. 1994). There is probably some truth in both. We should therefore continue unpacking and splitting the notion of privacy to find out, for each and every type of practical situation, exactly in which ways the social construction of this “hybrid” takes place. The conclusion is that it one should start considering the introduction of mobile telephones with data processing capabilities neither as telephones, computers nor Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen something in the middle. Rather they should be treated, at least with regards to the challenges of understanding and maintaining privacy, as an entirely new phenomenon in its own right. More elaborate theoretical thinking is needed. The notion of reflexivity (Beck 1986), for instance, springs to mind, since clearly a technology has been created to reach people anywhere, anytime, that at the same time makes it impossible for them to go certain places, for instance to take a shower in a public changing room after working out. Hong et al. do claim that security and privacy are related, but interestingly they see security as a precondition for creating systems that can maintain privacy. Looking at Thompson (op. cit.), in contrast, it would be interpreted as an opposite implication, namely that security (also in terms of the integrity of the underlying infrastructure) is a prerequisite for privacy, as it is, in fact, one of the constituent elements from which privacy is derived. Sheller and Urry, in a paper from 2003, make many useful observations, for instance that: “One of the key dilemmas of the 20th century concerned the overwhelming power of the state and market to interfere in and to overpower ‘private’ life. By contrast, in the 21st century, the emerging social problem is seen as the erosion of the ‘public’ by processes otherwise understood to be ‘private’ (Sheller and Urry, 2003, p. 107).” and they continue, referring to, but certainly not supporting, a argument that says that: “On every front is seems, the ‘public’ is being privatized, the private is becoming oversized and this undermines democratic life (ibid).” This has of course produced a discourse with results like the ones we saw in those two schools in the UK. They argue that the notions of ‘private’ and ‘public’ often is too static and regional, and that they encompass multifarious meanings. “Private-and-public life” is a complex and mobile hybrid. Mobile information systems contribute to “a more complex de-territorialization of publics and privates, each constantly shifting and being performed in rapid flashed within less anchored spaces (ibid, p. 108).” and so they argue that “social theory will need to develop a more dynamic conceptualization of the fluidities and mobilities that have increasingly hybridized the public and the private (ibid, 2003, p. 113).” which is exactly what this paper was geared towards, in that particular context of next generation mobile telephony. Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen References Barkuus, Louise, and Anind Dey (2003): Location-Based Services for Mobile Telephony: a Study of Users’ Privacy Concerns, Proceedings of the INTERACT 2003, 9TH IFIP TC13 International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, IRB-TR-03-024, July Beck, U. (1986) Risk society: towards a new modernity, London: Sage. Bellotti, V. and S. Bly (1996). Walking away from the desktop computer: distributed collaboration and mobility in a product design team. Proceedings of the 1996 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work. Boston, Massachusetts, United States, ACM Press. Bellotti, V. & Sellen, A. (1993): Design for Privacy in Ubiquitous Computing Environments. Proc. 3rd European Conf. on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, (ECSCW 93), G. de Michelis, C. Simone and K. Schmidt (Eds.), Kluwer, 1993, 77-92. Bergqvist, J., P. Dahlberg, et al. (1999). Moving out of the meeting room: exploring support for mobile meetings. Proceedings of the Sixth European conference on Computer supported cooperative work. Copenghagen, Denmark, Kluwer Academic Publishers. Boyle, M., Edwards, C. and Greenberg, S. (2000). The Effects of Filtered Video on Awareness and Privacy. Proceedings of the CSCW'00 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work [CHI Letters 2(3)], p1-10, ACM Press. Cesare, M. (2001). System and process modelling for design, management and performance evaluation of present and future mobile networks. Proceedings of the 4th ACM international workshop on Modeling, analysis and simulation of wireless and mobile systems. Rome, Italy, ACM Press. Yigal, B., C. Israel, et al. (2000). Dynamic session management for static and mobile users: a competitive on-line algorithmic approach. Proceedings of the 4th international workshop on Discrete algorithms and methods for mobile computing and communications. Boston, Massachusetts, United States, ACM Press. Dourish, P. (1993): Culture and Control in a Media Space, Proc. 3rd European Conf. on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, (ECSCW 93), G. de Michelis, C. Simone and K. Schmidt (Eds.), Kluwer. Edwards, W. K. (1994). Session management for collaborative applications. Proceedings of the 1994 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work. Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States, ACM Press. Fish, Robert S., Robert E. Kraut, Robert W. Root, Ronald E. Rice (1993): Video as a technology for informal communication, Communications of the ACM, Volume 36 Issue 1. Garfinkel, Harold. Good Reasons for 'Bad' Clinic Records in Studies in Ethnomethodology. (1967): 186-207 Gaver, W. W., Moran T. P., MacLean A., Lovstrand L., Dourish P., Carter K., Buxton W. (1992): Realizing a Video Environment: EuroPARC's RAVE System. In Proceedings of CHI '92 (Monteray, California, 3-7 May, 1992). ACM, New York, p. 27-35. Godefroid, Patrice. and James D. Herbsleb and Lalita Jategaonkar Jagadeesany and Du Li. (2000): Ensuring privacy in presence awareness: an automated verification approach. Proceedings of the 2000 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States p. 59-68. Goffmann, E. (1063): Behavior in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings, Free Press of Glencoe, 1963. Green, N., Harper, R., Murtagh, G. and Cooper, G. (2001), ‘Configuring the Mobile User: Sociological and Industry Views, Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, Vol..5, No.2, pp.146-56. Harmer J.A. (2003): Mobile Multimedia Services, BT Technology Journal, 21(3); pp. 169-180 Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen Harper, R. (1992): Looking at ourselves: an examination of the social organisation of two research laboratories. Proceedings of the 1992 ACM conference on Computer-supported cooperative work, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, p. 330-337. Hinckley, K., G. Ramos, et al. (2004). Stitching: pen gestures that span multiple displays. Proceedings of the working conference on Advanced visual interfaces. Gallipoli, Italy, ACM Press. Hong, Jason I., Ng, Jennifer D., Lederer, Scott and Landay, James A. (2004): Ubicomp at home and on the move: Privacy risk models for designing privacy-sensitive ubiquitous computing systems. Proceedings of the 2004 conference on Designing interactive systems, Cambridge, MA, USA, p. 91-100. Hudson, Scott E. and Smith, Ian (1996): Techniques for addressing fundamental privacy and disruption tradeoffs in awareness support systems. Proceedings of the 1996 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work, Boston, Massachusetts, United States, p. 248-257. Introne, L. D and Pouloudi (1999): A. Privacy in the Information Age: Stakeholders, Interests and Values. Journal of Business Ethics 22: p. 27-38. Kraut, Robert E., Ronald E. Rice, Colleen Cool, Robert S. Fish: Life and Death of New Technology: Task, Utility and Social Influences on the Use of a Communication Medium. Proceedings of the 1994 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work. Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States, pp. 13-21 Lacohée H.; Wakeford N.; Pearson I. (2003): A Social History of the Mobile Telephone with a View of its Future, BT Technology Journal, 21(3), pp. 203-211 Laurier, E. 2001. 'Why people say where they are during mobile phone calls', Environment and Planning D: Society & Space, v.19,4, 485-504 Licoppe, C., Heurtin, J. P. (2001): Managing One's Availability to Telephone Communication Through Mobile Phones: A French Case Study of the Development Dynamics of Mobile Phone Use. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 5, 2, pp. 99-108 Ling, R. (1996)."’One can talk about common manners!’: the use of mobile telephones in inappropriate situations." Report 32/96, Telenor Research & Development, Norway. Ling, Rich (2001): “We Release Them Little by Little”: Maturation and Gender Identity as Seen in the Use of Mobile Telephony. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 5(2): 123-136 Ling, R. & Yttri, B. (1999). "Nobody sits at home and waits for the telephone to ring: Micro and hypercoordination through the use of the mobile telephone." Report 30/99, Telenor Research & Dev., Norway. McArthur, R. L. (2001): “Reasonable expectations of privacy”, Ethics and Information technology 3:, pp 123-128. Pagani, D. and Mackay, W. (1993): Bringing media spaces into the real world. Proc. 3rd European Conf. on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, (ECSCW 93), G. de Michelis, C. Simone and K. Schmidt (Eds.), Kluwer, 1993, pp. 77-92. Palen, Leysia, Marilyn Salzman, and Ed Youngs (2000). Going Wireless: Behavior and Practice of New Mobile Phone Users. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW 2000), Philadelphia, PA, pp. 201-210. Palen, L. and Dourish, P. (1993): Unpacking “privacy” for a networked world, Proceedings of the conference on Human factors in computing systems, April 05-10, 2003, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, USA, pp. 129-136. Perry, M, O’Hara, K, Sellen, A, Brown, B and Harper, R (2001) Dealing with mobility: understanding access anytime, anywhere. ACM Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction, 8 (4), p 323-347. Ralph, D. T. (2002): 3G and beyond – the applications generation. BT Technology Journal 20(1), pp. 22-28. Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf Kristoffersen Sara, B., S. T. Alex, et al. (2003). Mobile phones for the next generation: device designs for teenagers. Proceedings of the conference on Human factors in computing systems. Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, USA, ACM Press. Sheller, M and Urry, John (2003); Mobile Trasformations of ‘Public’ and ‘Private’ Life. Theory, Culture and Society 20(3): pp. 107-125. Taylor, Alex S. and Richard Harper, The Gift of the Gab?: A Design Oriented Sociology of Young People's Use of Mobiles, Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), Volume 12, Issue 3, 2003, Pages 267 – 296. Number 8, 2005 http://www.ifi.uio.no/forskning/grupper/is/wp/082005.pdf