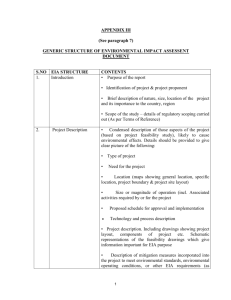

Environmental Planning in Sub-Saharan Africa: Environmental Impact Assessment at the Crossroads

advertisement