Uses and Valuation of the National Elk Refuge, Wyoming

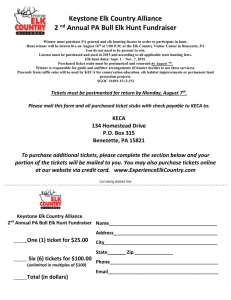

advertisement