Document 11508975

advertisement

Walden, Eric A., "Intellectual Property Rights And Cannibalization In Information Technology Outsourcing Contracts, MIS Quarterly,

Vol. 29, No. 4, December 2005, pp. 699-720.

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

RESEARCH ARTICLE

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS AND

CANNIBALIZATION IN INFORMATION

TECHNOLOGY OUTSOURCING

CONTRACTS1

By: Eric A. Walden

Information Sciences and Quantitative

Sciences

Jerry Rawls College of Business

Administration

Texas Tech University

Box 42101

Lubbock, TX 79409

U.S.A.

ewalden@ba.ttu.edu

is determined. This model is then modified to

account for the possibility of cannibalization of the

client’s benefit when multiple others are allowed

use of the software. The results show that the

best contractual structure depends strongly on the

environment.

Keywords: Contracts, outsourcing, economic

models, interorganizational relationships

Introduction

Abstract

This paper examines the question of how intellectual property rights in the software created during

information technology outsourcing relationships

should be divided. This paper expands on the

property rights approach developed by Grossman,

Hart, and Moore by recognizing that, with respect

to software, it is possible to separate excludability

rights from usability rights. These rights are

modeled and the contractually optimal distribution

1

V. Sambamurthy was the accepting senior editor for this

paper. Sandra Slaughter was the associate editor.

Natalia Levina served as a reviewer. The other

reviewers chose to remain anonymous.

Outsourcing is one of the most important issues in

information technology today. It has evolved from

a sporadic business practice into one that is

reshaping our entire global economy. Economic

approaches to understanding outsourcing have

focused largely on ownership of physical property

(Bakos and Nault 1997; Brynjolfsson 1994;

Grossman and Hart 1986; Hart and Moore 1988).

However, software is not physical property but

rather intellectual property, and as such it is not

constrained by the same physical or legal rules as

physical property. Thus, as software becomes an

ever-increasing proportion of information technology, it is necessary to update IT outsourcing

theory to consider the different types of ownership

that software allows.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4, pp. 699-720/December 2005

699

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

Software creation is an inevitable outcome of

many IT outsourcing relationships. This is trivially

true for software sourcing deals, but it is also true

for other outsourcing relationships, such as facilities management, integration, or implementation.

In the normal course of maintaining an information

system, old code is replaced with more efficient

code, filters and adaptors are written to connect

different systems, and new functionality is introduced to solve business problems. The scope of

this paper is the intellectual property rights associated with all of the various software created

during the relationship.

The property rights literature (Hart and Moore

1990; Maskin and Tirole 1999a) provides a starting

point for building a theory of software as intellectual property. However, software does not follow

the same physical laws as does the physical

property that has been previously studied. In particular, the use of software by one entity does not

physically preclude the use of that same software

by other entities. Therefore, to understand how to

assign intellectual property rights in software

created during an outsourcing relationship, it is

necessary to modify property rights theory, in order

to create intellectual property rights theory.

This work undertakes that task. First, it recognizes

that software gives way to ownership structures

which are fundamentally different than those of

physical property. Second, the intellectual property rights in software in an outsourcing relationship are modeled. Third, implications for the

optimal distribution of software intellectual property

rights in a variety of different possible environments are elucidated, including the consequences

of cannibalization.

This paper makes several important contributions.

Most importantly, it creates a theoretical basis for

the future study of intellectual property in IT. This

grants both practitioners and researchers a

starting point for the formulation of intellectual

property issues, rather than forcing them to rely on

physical property theory as a basis for a nonphysical thing. This work also provides some

ready-made solutions for empirical testing by

700

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

academics and the formulation of intellectual

property contracts by practitioners.

This paper follows Whang (1992) in observing

real-world contracts to inform my theory building.

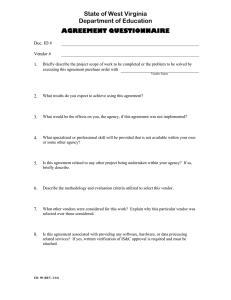

Three contracts were procured from a private

source in order to serve as a guide for the

development of a realistic model. This work finds,

as did Whang, that, “while this is a small set of

cases, there is a substantial amount of commonality among these contracts and they merit

consideration, even if they are not comprehensive”

(1992, p. 309).

Specifically, the contracts

assigned two different property rights: the right to

use and the right to exclude others from using. In

the traditional property rights literature, these two

rights are inexorably joined because if one entity

uses a particular physical asset, others are automatically excluded from using that same asset.

However, with respect to software, these two rights

can be (and apparently are) separated and

assigned independently.

Managers must decide how to allocate property

rights between the parties to the contract.

Software is nonphysical and, thus, the range of

possible allocations is not bounded by the same

constraints that bound the ownership of physical

property. This paper shows that the optimal allocation of intellectual property rights depends on

three things: the ability of each firm to enhance

the internal usefulness of the intellectual property,

the ability of each firm to enhance the external

marketability of the intellectual property, and the

loss of competitive advantage arising from widescale distribution of the intellectual property.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. In the

next section, the literature on contracting for IT

and the property rights literature are reviewed.

Next, the property rights literature is extended to

account for intellectual property’s ability to separate usability and excludability rights. Following

that, propositions explaining some of the circumstances under which each of the intellectual

property right allocations are optimal are

developed. Finally, a discussion of the contribution, limitations, and directions for future research

is presented.

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

Literature Review

To understand how intellectual property rights are

managed in IT outsourcing, it is necessary to

establish some definitions. In outsourcing, two

firms engage in a relationship. The relationship is

the set of all possible situations and actions the

two firms can face. The firms draft a contract to

define the parameters of the relationship. A contract is made up of sections, which address a specific aspect of the relationship (transfer of employees, for example). Each of the sections can

be thought of as being complete or incomplete.

A complete contract specifies all the actions that

each party would take in response to every

possible state of the world. This is an idealized

concept of a contract, but in reality it may have

value only where most of the important states of

the world, and important actions, can be specified.

However, in a long-term pervasive relationship,

such as that addressed in the contracts of this

study, completeness is an unrealistic goal.

Incomplete contracts are contracts that focus on

offering alternative ways to deal with aspects of

the relationship that are not easily addressable by

simply specifying all possible contingencies. For

example, an incomplete contract may specify

meetings (Ang and Beath 1993; Stinchcombe

1985) or ownership (Bakos and Brynjolfsson

1993a; Grossman and Hart 1986) to deal with

situations where appropriate actions cannot be

specified ex ante. While there is explicit recognition that no contracts are, in reality, complete,

there is lively debate on the extent to which

complete contract theory offers valuable insights

(see Hart and Moore 1999; Maskin and Tirole

1999a; Tirole 1999). In practice, actual contracts

contain both complete and incomplete sections.

Ownership is an alternative mechanism put into a

contract to help address the incompleteness of the

contract, with respect to some aspect of the relationship. This work follows the Grossman–Hart–

Moore definition of ownership: “all the rights

except those specifically mentioned in the contract” (Grossman and Hart 1986, p. 692). This is

an important point. Neither Grossman–Hart–

Moore nor this work claim that there are not parts

of the contract that are complete. Rather, Grossman, Hart, and Moore assert that, after all the

cost-effective clauses are written into a contract,

there are still important aspects of the relationship

that have not been defined. Thus, the contract

grants ownership of an asset to allow the

remaining states of the world and corresponding

actions concerning that asset to become the

responsibility of one of the parties.

The question immediately arises as to why contracting parties would cover some contingencies

directly, but leave others to be handled by alternative mechanisms, particularly when the alternative

mechanisms frequently result in a less-than- optimal solution. One reason is the cost of writing a

contract. Simply stated, if the expected cost of

writing a contract clause exceeds its value, then

the clause should be omitted (Battigalli and Maggi

2000). Another frequently cited reason is the

bounded rationality of the contract writers (Williamson 1985). Segal (1999) offers a rigorous model

of this situation, in which increasing the complexity

of the environment leads to a preference for incomplete contracts. Others simply cite the fact

that real-world contracts are never observed to be

fully contingent (Masten 2000). The important

point is that there is ample theoretical and empirical evidence to support the claim that contract

writers leave contracts incomplete with respect to

subsets of the relationship. Moreover, specific to

this work, the observed contracts were incomplete

with respect to software assets and the incompleteness was resolved with ownership. Therefore, the property rights approach seems to be a

reasonable base upon which to build additional

theory.

The property rights approach (Grossman and Hart

1986; Hart and Moore 1990) is an extension of

transaction cost economics (Coase 1937; Williamson 1975, 1985) and, as such, is aimed at

explaining the boundaries of the firm. The property rights approach posits that two firms create

value by working together. More value is created

if the firms cooperate than if they act indepen-

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

701

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

dently, creating a quasi-rent.2 The property rights

approach follows transaction cost economics in

recognizing that this quasi-rent cannot be entirely

divided by an ex ante contract. Thus, the property

rights approach is also known as incomplete

contract theory, although that is a bit of a misnomer, since many contracting theories recognize

the inability of firms to write complete contracts

(Hart 1995; Hart and Holmstrom 1987; Maskin and

Tirole 1999b; Masten 2000).

The Grossman–Hart–Moore calculus assumes

that investment and output are observable, but not

verifiable. The former avoids some stochastic

elements, making the model more tractable and

distinguishing it from agency theory. The latter

simply means that the courts cannot verify the

investment and, hence, it cannot be contracted

upon.

Therefore, contracts contain clauses

describing property rights rather than detailing the

investments that should be made in creating those

assets. This assumption has received considerable attention (Hart and Moore 1999; Maskin and

Tirole 1999b; Segal 1999; Tirole 1999).

One argument in support of this assumption is that

the set of states of the world are too complex to

specify ex ante. However, through the life of the

contract, the range of potential states becomes

smaller as events unfold, so that the participants

can observe and make informed decisions after

the contract is signed (Grossman and Hart 1986;

Hart and Moore 1988; Segal 1999). Another argument is that verification is costly (Hart 1995; Hart

and Moore 1999). This is persuasive, considering

that lawsuits can take years (or decades) to

resolve and cost millions of dollars. Yet another

argument (Hart 1995; Hart and Moore 1988), is

that there is no legal provision to prevent renegotiation, and in the absence of such a provision

verifiability is moot. Finally, specific to this paper,

each of the contracts examined did, in fact, specify

ownership of intellectual property rather than

define the nature of the investments to be made.

2

A quasi-rent is income above opportunity cost. In this

case, the quasi-rent is the difference between the value

created by working together and the value created by

acting independently.

702

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

The existence of a quasi-rent leads to inefficiencies as each firm recognizes that it may not

get the full benefit of its investment. The property

rights approach specifies that the firms will engage

in ex post bargaining to split the surplus, where the

bargaining position and, hence, the bargaining

outcome are functions of ownership. If a physical

asset is solely owned by one firm, then that firm

will reap 100 percent of the return on any investments made in the asset and, hence, will invest at

an optimal level. If a physical asset is jointly

owned, each firm anticipates the fact that it will

have to share the value generated by its investment, and each firm underinvests. Simply stated,

the problem is that each firm pays 100 percent of

its own investment, but receives only half of the

value of that investment.

The property rights approach proposes ownership

as the solution to this problem. When firms

bargain over the quasi-rent attributable to an

asset, the owner of the asset will receive the entire

value. Creating value with an asset requires the

owner’s consent, and the owner can charge the full

value created for his consent. The essential

prescription of the property rights approach is that

the firm whose investment in an asset creates the

most value should be the owner of that asset. This

result occurs because the owner will make greater

investments in the asset.

The property rights approach has been applied in

prior IT literature to help explain the impact of

information technology on the size of firms. The

proposition is that certain information is inalienable

from the human agents that produce it and, thus,

ownership is predetermined (Brynjolfsson 1994).

This basic idea helps explain why, even when IT

significantly reduces coordination costs, firm size

may not change. That is to say, in spite of the fact

that IT offers a technical solution to outsourcing, in

general, it does not change the incentive structure

resulting from ownership and, thus, has little actual

effect on the level of outsourcing.

Building on this idea, IT literature has shown that

ownership considerations may also lead to firms

using a smaller number of suppliers in order to

give each supplier greater ownership and, hence,

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

greater incentive to invest (Bakos and Brynjolfsson

1993b). Carried to its logical conclusion, this

stream of research has shown that in the presence

of indispensable agents (an agent with inalienable

assets that are necessary for value), the formation

of coalitions is the optimal response (Bakos and

Nault 1997).

This makes a case for less

outsourcing in the face of IT, rather than more.

An important thread to pick out in prior IT literature

concerning the property rights approach is that of

restricted ownership. Generally, the underlying

assumption is inalienability of information assets,

which restricts ownership to a specific firm or

agent. While there are certainly information assets

that are inalienable, this work investigates the

opposite issue. Rather than considering restrictions on ownership, this work considers IT-induced

extensions to ownership.

This is an important point and it bears additional

consideration. The practice of IT is solving

business problems with technology, and prior

literature has certainly demonstrated a business

problem. As Brynjolfsson observes, “merely

embodying information in a tradable form can

‘create’ a great deal of value even without increasing the stock of knowledge” (1994 p. 1652).

This task of embodying information in a tradable

form is an important business problem, which is at

the core of advances in object-oriented paradigms.

Thus, IT practice has spent considerable time and

effort in implementing technological solutions that

enable—force, in fact—new ownership structures

for software. It is time for theory to catch up with

these advances and consider the impacts of these

enhanced ownership structures in the context of

the property rights approach.

in the property rights literature. Ownership in all

applications of the property rights model, to date,

means the ability to exclude other parties from the

value generated by an asset. Grossman and Hart

(1986, p. 694) cite an Oliver Wendell Holmes’

definition of property rights, which concludes with

the sentence: “The owner is allowed to exclude

all, and is accountable to no one but him.” The

essence of ownership in the property rights literature is that the owner has veto power over value

creation. When it comes time to derive value from

an asset, the owner of the asset must give his

approval, or no value may be created.

There are two possible ownership structures under

this definition. One firm may be the sole owner of

the asset, in which case it derives sole value from

the asset. Another possibility is that both firms

jointly own the asset, so that each has veto power

over value creation. In this case, each firm has

equal bargaining power, and the value is assumed

to be split equally between them. While this leads

to a parsimonious model, it is far too simple a view

of ownership.

Legal ownership is richer than simple veto power,

in that it is a complex bundle of rights.3 Complex

combinations of rights can be given in a contract to

offer a much greater range of incentives. Grossman and Hart (1986, p. 692) recognize this bundle

of rights issue when they state “ownership is the

purchase of these residual rights of control.”4

However, in the interest of parsimony, all of these

rights are lumped together into a single construct

called ownership.

The spirit of economic inquiry is to begin with the

simplest possible model at the expense of overly

3

Theory Development

United States Code Annotated, Title 17, “Subject Matter

and Scope of Copyright,” §106, 2002.

4

Ownership

The crux of the basic property rights model is the

idea that ownership provides incentives. Thus, it

is important to clarify what is meant by ownership

As a reviewer points out, it is important to note that

where contracting is easy, one would expect complete

contingent contracts that simply rewarded the vendor

based on action. The Grossman–Hart–Moore model

recognizes that some things are easy to contract on and

only considers the part of the relationship where things

are difficult to contract. Hence, the concept of residual

rights, rather than total rights.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

703

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

restrictive assumptions and then to build knowledge by relaxing those assumptions. This is precisely what is done here. This paper relaxes the

assumption that the bundle of property rights is a

whole, thereby enhancing and providing a deeper

understanding of the concept of property rights.

Moreover, the set of rights associated with an

asset depends on the nature of the asset. For

example, the set of rights attachable to a piece of

land will be different from those attached to an

employee, which will in turn be different from those

attached to software. Explicit recognition of this

allows for the construction of a richer theoretical

framework for property rights—one that generates

useable recommendations for practice and provides a basis for empirical investigation. This work

seeks to extend the theoretical implications of the

property rights literature by recognizing and

incorporating a richer set of property rights into the

basic model.

New Types of IT-Enabled

Property Rights

Property rights can create value in two ways. The

first, usability, allows the owner to actually deploy

the asset to generate profit. This is sometimes

called communal rights (Alchian and Demsetz

1973). The second, excludability, allows the

owner to charge for access to the asset. This

distinction is not informative in the case of physical

or even human capital assets because their finite

nature necessarily means that productive use of

an asset by one firm results in its exclusion from

another firm. An individual employed for the benefit of firm 2 for one year is not employed for the

benefit of firm 1 during that same year. A machine

being used by firm 1 cannot be used by firm 2.

There are obvious time-sharing options, but

because physical and human capital are finite,

there always exists a limit to their use.

Software, however, has no such restrictions

(Kauffman and Walden 2001; Shapiro and Varian

1999). Two or more firms can simultaneously, and

to full extent, use the same software at the same

704

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

time. Thus, this distinction between ownership as

productive use and ownership as excludability

becomes important when dealing with software.

This work investigates outsourcing of software

assets and is most applicable to software development. It can be applied to a varying degree to

other types of outsourcing depending on how

much of the outsourcing relationship is concerned

with intellectual rather than physical property.

Clearly, software allows for very different ownership characteristics than physical assets. While

ownership and possession are often linked for

physical assets, as far as software is concerned,

possession is a meaningless term. In fact, virtually

all ownership characteristics of software are purely

conceptual and defined by law, rather than by

physics. Thus, to use the property rights literature

for software requires considerable reconceptualization of the idea of ownership. (This is not only a

problem in economics and IT, but also an ongoing

issue in the field of law.5)

The nonphysical restrictions of software allow

ownership to be changed in two ways. First,

excludability and usability may be separated. This

means that a firm may be given the right to use an

information asset without also being given the right

to exclude others from its use. This does not apply

to physical assets because by using the asset, one

necessarily excludes others from its use. This is

relevant to even a very large physical asset that it

would seem multiple agents could simultaneously

use, such as a lake. If one is granted usability,

one may pump out all of the water or dump in toxic

chemicals, in effect excluding anyone else from

using it. Thus, if one agent has given away the

right of usability, his ability to exercise the right of

excludability is seriously impaired, because the

value to the remaining agents depends on how the

agent that has usability rights uses the asset. This

arises directly out of the physical law that a body

cannot occupy two different places at the same

5

For a primer on this see the Congressional Budget

Office’s August 2004 publication “Copyright Issues in

Digital Media,” available online at http://www.cbo.gov/

showdoc.cfm?index=5738.

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

time.6 Thus, by using a physical asset, an agent

effectively builds a “fence” around the physical

object, thereby excluding others. However, the

information embodied in software can occupy

multiple places at the same time.

The second enhancement is the consideration of

multiple replications of the same right. This allows

for identical and independent ownership to go to

multiple firms. One implication of this is that it no

longer makes sense to simplify the models to

include only two firms, as typical property rights

models do. The model must be expanded to

recognize that excludability still has value to one

firm even if another firm has usability rights. The

idea of independent ownership means that multiple

firms can have property rights without having to

share the benefits, as discussed below.

The Model

Following the Grossman–Hart–Moore calculus

(Grossman and Hart 1986; Hart 1995; Hart and

Moore 1988, 1990), let us consider a relationship

between a risk-neutral client and vendor. In the

initial period, they write a contract that describes

the ownership structures and a transfer price p

from client to vendor. The parties use the transfer

payment to achieve a cooperative bargaining solution that maximizes joint surplus. The ownership

structure that maximizes joint surplus is guaranteed by allowing the party that is better off under

that ownership structure to pay the other party

some amount to compensate it for loss of

ownership.

Hart and Moore say that the contract “specifies the

conditions of trade” (1988, p. 757). They allow

either one or zero units to be traded, which means

that the client will either gain use of the item produced or will not. In this case, the asset of desire

is the software created in the relationship, and thus

trade is not an appropriate term. A trade implies

taking something from one party and giving it to

another. While this is certainly a restriction on

physical assets, it is not a restriction for information assets. It is not necessary for the vendor to

give up use of the item for the client to also have

use of the item. Thus this work explicitly recognizes that the contract defines the terms of use

rather than the terms of trade.

After the contract is signed, the client (c) and

vendor (v) learn about the state of the world and

make investments (i) in the software assets, ic and

iv. The idea of learning the state of the world can

be made more concrete by thinking about it as the

knowledge revelation that occurs between the time

a project is begun and the time it is completed. As

this knowledge is revealed, the client and vendor

make investments in improving the assets. This

work follows the Grossman–Hart–Moore model in

assuming that investments and outputs are

observable, but not verifiable.

Several types of benefit are generated by investments. Grossman, Hart, and Moore assume that

the only value generated is a gain from trade.

However, as this work is concerned with gains

from use, it is necessary to consider more potential

sources of gain. This work considers gain to the

client from use, Uc, gain to the vendor from use,

Uv, and gain from potential resale, S. Grossman,

Hart, and Moore were able to ignore the latter two

gains by assuming that the highest value use of

the asset was with the client, and that only one

entity could use the asset. However, if multiple

entities can simultaneously use the asset, then

each value must be considered independently.

For tractability, all of the potential value from the

resale market is lumped together into one value, S.

One important consideration is that resale may be

easily verifiable, and hence, contractible.7 Certainly, some aspects of resale are verifiable and by

the Grossman–Hart–Moore calculus are excluded

from consideration. However, there are situations

in which resale is imperfectly verifiable. Often,

resale is difficult to verify because resale is done at

the object level rather than the system level. That

is to say, the vendor redeploys some of the objects

to achieve speed and scale, but these objects are

6

This may not be true for quantum particles, but,

thankfully, contracts are not generally written at the

quantum level.

7

I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

705

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

deployed with other objects. This makes it difficult

to sort out each object’s contribution to value.

Furthermore, resale is difficult to verify in software

development because there are often a number of

complementary products that go along with software sales, such as maintenance, upgrades, and

integration. On the other hand, systems may be

designed with commercialization in mind

(DiRomualdo and Gurbaxani 1998), in which case

verifiability would be built into the contract. A promising direction for future research is an examination the boundaries of verifiability of resale. However, for the purposes of this paper, we assume

that there are some aspects to resale that are

unverifiable.

In the second period, after investments ic and iv are

made and the values of Uc, Uv, and S are realized,

the client and vendor costlessly renegotiate a contract dividing these values. The total pie then is

π total = Uc (ic , iv ) + Uv (ic , iv ) + S(ic , iv ) − ic − iv (1)

where the cost of investment is normalized to the

level of investment and Uc, Uv, and S are twice

differentiable, increasing, positive, concave

functions.

The innovation in equation (1) is that, because the

asset under consideration is an information asset,

all the relevant entities can conceivably use the

asset simultaneously. In the Grossman–Hart–

Moore model, only one entity could benefit from

use of the asset. Also, note that investments are

considered to be general, in that they create value

for all the entities involved.

As in the Grossman–Hart–Moore calculus, the

payoff to each party in the second period depends

on each party’s bargaining power in the second

period renegotiation, which, in turn, depends upon

the rights contracted for during the first period.

This work allows for two separate property rights:

excludability and usability. These cannot be

separated for physical assets, but may be for

information assets.

Excludability is the right to engage the legal

apparatus of the nation to force other entities to

706

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

cease use of the asset (or to compensate the

property right owner for damages). With the right

of excludability comes the choice of exercising that

right. In other words, the ability to sell. An entity

with excludability rights can contract with other

entities not to exercise those rights. In this case,

the excluder sells its promise not to exclude. An

entity can choose not to exclude itself. Where

both parties have excludability rights, this work

follows Grossman–Hart–Moore in assuming that

Nash bargaining takes place, giving each party

one-half of the payoff from excludability rights.

Thus, if both parties have excludability rights, then

generating outside value from the asset requires

approval of both parties, who then bargain over the

surplus and receive one-half of that value.

Usability takes precedence over excludability, in

that it allows the property right owner to disengage

the nation’s legal apparatus. Usability is a promise

that no one can exercise excludability. Usability

allows the owner to take any private actions with

the asset that he desires. However, usability does

not allow the right of sale. Those with usability

rights cannot offer any threat to stop others from

using, and hence cannot sell a promise not to

exclude. For example, the author has usability

rights on the word processing software used to

write this paper. I can write what I want, but I

cannot resell, because I cannot credibly threaten

anyone else’s use of the software. No one will pay

me not to engage the legal apparatus of the

nation, because I have no rights to engage that

legal apparatus.

Each party’s property rights are an ordered pair of

rights (Re, Ru), where Re denotes excludability

rights and can take values E and N, corresponding

to the presence or absence of excludability rights.

Ru denotes usability rights and can take values U

and N, corresponding to the presence or absence

of those rights. Usability rights allow the owner to

maintain all of the value from the owner’s use. In

general, excludability rights allow the owner to

garner some share of the value of resale S of the

software. The payoffs to different ownership combinations are listed in Table 1. The investment

levels are suppressed, because the client always

pays ic and the vendor always pays iv. Likewise,

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

Table 1. Payoffs to Second Period Game as a Function of Ownership (Client’s Payoff

is on Top)

Vendor

(E,U)

(E,N)

(N,U)

(N,N)

(E,U)

(E,N)

(N,U)

(N,N)

Uc + ½S

½Uc + ½S

Uc

½Uc

Uv + ½S

½Uc + Uv + ½S

Uv + S

½Uc + Uv + S

Uc + ½Uv + ½S

½Uc + ½Uv + ½S

Uc

½Uc

½Uv + ½S

½Uc + ½Uv + ½S

Uv + S

½Uc + Uv + S

Uc + S

Uc + S

Uc

0

Uv

Uv

Uv

Uv

Uc + ½Uv + S

Uc + ½Uv + S

Uc

0

½Uv

½Uv

0

0

the transfer payment p is also suppressed

because the client always pays p and the vendor

always gains p. The derivation of this table is

discussed in the appendix.8

Rather than discuss 16 ownership structures, the

table is simplified to rule out some irrational combinations. In addition, the symmetry of the table is

used to avoid discussions that are identical but for

a change in subscripts.

First, notice that the four ownership structures in

the bottom right of the table are not rational

choices. They are not rational, in the Pareto optimal sense, because other ownership structures

exist which make at least one of the parties better

off without making the other worse off. For

example, [(N,U), (N,U)] can be improved upon by

granting excludability to both of the parties [(E,U),

(E,U)], because each will get what they would

under [(N,U), (N,U)] plus one-half S, which is

positive.

Second, notice that [(E,U), (N,U)] and [(E,N),

(N,U)] have identical payoffs. The only role ownership plays is in determining payoffs. Hence,

[(E,U), (N,U)] and [(E,N), (N,U)] have no relevant

differences. For simplicity, assume that (E,U) will

be chosen over (E,N) if the payoffs are identical.

8

The appendix for this paper is located at http://misq.org/

archivist/vol/no29/issue4/WaldenAppendix.pdf.

This also eliminates [(E,N), (N,N)], [(N,U), (E,N)],

and [(N,N), (E,N)].

This leaves the leftmost column and the topmost

row, which are symmetrical, and the [(E,N), (E,N)]

ownership structure. Because the leftmost column

is symmetrical to the topmost row, only the

topmost row will be discussed. This yields five

ownership structures and associated payoffs, as

described in Table 2. The transfer price and

investment levels are included for completeness.

First Best

It is clear from (1) that the first best level of

investment is the level of investment that solves

∂U c (ic , iv ) ∂U v (ic , iv ) ∂S (ic , iv )

= 1 (2)

+

+

∂i c

∂ic

∂i c

and

∂U c (ic , iv ) ∂U v (ic , iv ) ∂S (ic , iv )

= 1 (3)

+

+

∂i v

∂iv

∂i v

In this first best situation, both the client and

vendor equate their marginal contribution to profit

to the marginal cost of investment. However, this

first best will not be achieved, because under no

proposed ownership structure do the two firms

face a payoff that yields these two first-order

conditions (see appendix). Thus, a second best

solution must be found.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

707

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

Table 2. Reduced Payoffs From Different Ownership Structures

Ownership Structure

[(client rights),(vendor rights)]

Client Payoff

Vendor Payoff

[(E,U), (E,U)]

Uc + ½S – p – ic

Uv + ½S + p – iv

[(E,N), (E,U)]

½Uc + ½S – p – ic

½Uc + Uv + ½S + p – iv

[(N,U), (E,U)]

Uc – p – ic

Uv + S + p – iv

[(N,N), (E,U)]

½Uc – p – ic

½Uc + Uv + S + p – iv

[(E,N), (E,N)]

½Uc + ½Uv + ½S – p – ic

½Uc + ½Uv + ½S + p – iv

Second Best

The contracting parties’ problem is to choose the

ownership structure that maximizes the joint

return. This means choosing the ownership structure that maximizes (1) subject to the constraint

that the chosen level of investment is the solution

to the first-order conditions detailed in the appendix. Thus, investment is a function of ownership structure and joint surplus is a function of

investment.

In general, the optimal ownership structure depends on how each party’s investment creates

value, and none of the structures under consideration dominate any others. Thus, to evaluate the

benefits of different structures, it is necessary to

make meaningful assumptions about the effects of

investments.

Let the term is primarily sensitive to mean that the

level of a value source, V 0 { Uc, Uv, S }, is sensitive (primarily) to one type of investment, ik, in the

sense that MV/Mij = g(MV/Mik), where j, k 0 {client,

vendor}, j … k, and g is arbitrarily small. This

means that only one entity’s investments bring

about any meaningful change in value and the

other entity’s investments have an arbitrarily small

effect.

Let the term depends equally on mean that the

level of a value source, V 0 { Uc, Uv, S }, is determined equally by each entity, in the sense that V =

f(ic) + f(iv), where f is an increasing, concave,

twice-differentiable positive function. Because

708

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

both entities have the same f, the investments by

each have the same impact.

Let the term similar sensitivity mean that for any

two value sources, V, W 0 { Uc, Uv, S } and any

two types of investment, j, k 0 {client, vendor},

MV/Mij = (1 + g)MW/Mik, where g is arbitrarily small.

This simply means that the level of each value

source changes in a similar manner.

Let the term return to investment falls off more

rapidly mean that for any two value sources, V, W

0 { Uc, Uv, S } and any two types of investment, j,

k 0 {client, vendor}, if M2V/Mij2 > M2W/Mik2, then the

return to ij in V falls off more rapidly than the return

to ik in W. This literally refers to the curvature of

the value function. If one value function has

greater curvature, then the impact of investment

on value creation falls off rapidly relative to a

function with less curvature.

Define a source of value, V, as being relatively

more sensitive to an investment type, ij, than value

source, W, if MV/Mij > MW/Mij + q, for all ij, where q is

arbitrarily large. This means that for any given

value of ij, the marginal benefit of investing in V is

much greater than the marginal benefit for

investing in W.

Define a source of value V to be sensitive over a

wide range to a type of investment, ij, if M2V/Mij2 =

g(MV/Mij), where g is arbitrarily small. This simply

means that the rate of change of the first derivative

is small relative to the size of the derivative. Thus,

the impact of investment, ij, is consistent over a

large range of values.

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

Given these definitions, each of the ownership

structures can be evaluated. The conditions presented are not exhaustive, but they are representative of real situations. Other sufficient conditions

exist that may make one ownership structure

preferred to others. All proofs are located in the

appendix.

Proposition 1: When [(E,U), (E,U)] IS

Second Best. If Uc is primarily sensitive

to ic, Uv is primarily sensitive to iv, S

depends equally on ic and iv, and the

sensitivity of Uc to ic is similar to the

sensitivity of Uv to iv, then [(E,U), (E,U)]

ownership is the second best (i.e., it is at

least as good as any other ownership

structure, but fails to be optimal).

This is an intuitive ownership structure where each

party gains the full value of their internal benefit

and the parties share the external benefit equally.

This works if the internal benefit to each party is

unilaterally determined by the party in question.

However, these conditions are not what one would

expect in a typical outsourcing arrangement. In

typical outsourcing, the client’s benefit depends on

the vendor’s investment as much, or more, than it

depends on the client’s. Outsourcing is usually

done to take advantage of the relative superiority

of the vendor.

There are arrangements where this type of

contract would work well. This sort of equality

contract would tend to work well in joint research

and development projects (Jap 2001). Arrangements that are created more for developing a

sellable product than for internal use would be well

served by such a contract. Thus, it is not surprising that the contracts viewed for this work do

not exhibit this ownership structure.

Proposition 2: When [(E,N), (E,U)] Is

Second Best. If Uv is primarily sensitive

to iv, Uc depends equally on ic and iv, S

depends equally on ic and iv, the sensitivity Uc with respect to ic is similar to

the sensitivity Uc with respect to iv, and Uv

is sensitive over a wide range to iv, then

[(E,N), (E,U)] ownership is the second

best.

It is easy to imagine a situation where a technically

competent vendor desires to enter a new business

domain about which it knows very little. The

vendor can then partner with a client that has a

great deal of in-depth business knowledge in the

domain. The combination of technical proficiency

and in-depth business knowledge can then

produce valuable software that the client itself can

use, but that also has good resale potential. A

variation on this would be a situation in which the

vendor’s benefit was very small, but the client

required the vendor’s help, and the software being

designed had significant resale value.

Proposition 3: When [(N,U), (E,U)] IS

Second Best. If Uc is primarily sensitive

to ic, and both Uv and S are primarily

sensitive to iv then [(N,U), (E,U)]

ownership is the second best.

These conditions suggest that value creation is

largely independent so that investment by the

client creates value for the client and investment

by the vendor creates value for the vendor. Under

such circumstances, it is not clear why either party

would desire to form a relationship rather than

produce independently.

This concern could be addressed if Uc = fc(ic) + [giv

+ q], where g is small, q is a large constant, and

the term in brackets is the effect of the vendor’s

investment. In this case, the vendor has a set of

standardized, high-value investments that it makes

but, after making those standard investments,

additional vendor investment has negligible impact

on value creation.

This seems like a reasonable perspective on

typical outsourcing arrangements. The vendor has

some set of general best practices that it brings to

the relationship, which create real value. However, all the specific fine-tuning depends on the

client’s efforts to adapt the software to its particular

processes (or its processes to the software).

Proposition 4: When [(N,N), (E,U)] Is

Second Best. If all sources of value

depend primarily on the vendor’s iv, then

[(N,N), (E,U)] ownership is the second

best.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

709

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

If the vendor is particularly competent, and the

client is not, then this may be a very realistic

scenario. In such a case, it makes sense to give

all of the rights solely to the vendor. However, this

leaves the client exposed and allows the vendor to

appropriate some of the value the client may gain

from the use of the software.

This ownership structure also makes sense when

a vendor hires a domain expert for advice.10 In

such a case, the arbitrary labels client and vendor

are misleading, because the vendor is paying the

client for services. However, the model is flexible

enough to account for this situation, which is

common in practice.

At first glance one would not expect a client to ever

agree to such a contract. However, upon reflection, it seems that clients do sometimes agree to

such a contract, and rationally so. Clients frequently outsource software development because

of a sense of internal frustration. These clients do

not feel that they can effectively manage software

development. They recognize that they need software to handle a function, but they also recognize

that they lack the expertise, in-house, to build the

software. If these types of clients are prudent,

they will grant all of the rights to the vendor in

order to maximize vendor investment, then seek a

transfer price, p, that enables them to gain the

benefits of the system up-front. In other words,

they negotiate a negative p. In essence, they sell

the vendor the right to take advantage of them in

the future for current gains.

In sum, this ownership structure can make sense

even though it reduces incentive for client investment. It makes sense because it allows a client to

gain some up-front payment that compensates the

client for future appropriation by the vendor.

However, it probably also causes other difficulties

beyond the scope of this analysis (Singh and

Walden 2003). Nonetheless it should be recognized and explored.

This may seem like a purely academic logic

exercise, but evidence suggests that it is not.

Cash infusions from outsourcing vendors to clients

are common (Lacity and Hirschheim 1993). The

Outsourcing Institute reports that one of the top 10

reasons for outsourcing is, in fact, to gain a cash

infusion.9 In many full sourcing agreements, the

vendor will purchase all of the client’s hardware

and leases for more than market price. It is

common for vendors to give clients low interest

loans (Lacity and Hirschheim 1993). This suggests that the transfer price agreed upon in the

original contract is, in fact, negative, with the

vendor actually paying the client. Of course, this

payment is then recouped in later periods (Singh

and Walden 2003). Clients frequently cite rising

prices in the later years of the contract as a major

cause of friction (Barthelemy 2001).

Proposition 5: When [(E,N), (E,N)] Is

Second Best. If the value from all

sources depends equally on ic and iv, the

return to ic with respect to Uc falls off

more rapidly than the return to iv with

respect to Uc, the return to iv with respect

to Uv falls off more rapidly than the return

to ic with respect to Uv, and Uc is relatively

more sensitive to iv than Uv is, then

[(E,N), (E,N)] ownership is the second

best.

This situation is likely to occur when the software

development is truly a partnership with the client

supplying business expertise and the vendor

supplying technical expertise. This represents the

ideal of development as a partnership with proper

incentives for both vendor and client. However,

such a partnership only makes sense if both

parties actually contribute equally.

Summary of Ownership Structures

Each of the ownership structures may be second

best in different situations. The conditions provided are not exhaustive, but do offer some indication of meaningful conditions that make each dif-

9

See http://www.outsourcing.com/content.asp?page=

01b/articles/intelligence/oi_top_ten_survey.html.

710

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

10

I thank an anonymous reviewer for this insight.

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

ferent ownership structure superior to the others.

There are two important take-aways. First, this

work details sufficient conditions for each structure to be second best. This knowledge can guide

practitioner creation of contracts, and provides

testable hypotheses for future academic work.

Just as important is the fact that there are so many

nondominant ownership structures. There is a tendency to search for a globally best contract, with

relative disregard for the complexity of choices.

Some commentators suggest that outsourcing

should be a partnership, with each participant

working toward creating shared value. However,

as the analysis shows, this type of contract only

makes sense if the participants are equal partners.

In other situations, it may make sense to grant the

vendor considerable ownership if value is primarily

sensitive to vendor investment. In yet other situations, it makes sense to give each party the fruits

of their labor, and nothing else, but still form a

partnership. The point is, the ideal contract depends on how each party’s investments influence

value creation, and it is not likely that this will be

the same for every relationship. The ideal ownership structures as a function of the relational

environment are displayed in Table 3.

Cannibalization

Because software is intellectual, not physical,

property and can be sold to many agents simultaneously, cannibalization must also be considered. Cannibalization occurs when the vendor

uses or sells software that would generate more

value to the client if the client were the sole user

In such situations, the software that is developed

may have greater value to the client if only the

client has access to that software. This can be

operationalized in the model by making the client’s

value a negative function of resale value.11 In this

case, the joint benefit becomes

11

I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

[

π total = U c ( i c , i v ) −δS ( i c , i v )

]

+ U v (i c , i v ) + S (ic , i v ) − i c − iv

(4)

The term in brackets is the client’s new benefit

function and cannibalization is assumed to enter

linearly. The coefficient * is assumed to be

positive.

It is clear that the potential benefit under cannibalization will be smaller than the benefit absent of

cannibalization because a negative term has been

added to the benefit function. This also means

that the benchmark of first best will be different, so

that the same levels of investment that were first

best without cannibalization will no longer be first

best. However, there are several other effects

which are less clear.

Proposition 6: The Effect of Cannibalization on Client Incentives. If the

net benefit to client use of the software is

[Uc(ic, ic) – *S(ic, ic)], then the client will

have reduced incentive to invest under

each of the five ownership structures.

This is an intuitive result, but is only made accurate because none of the five ownership structures

fully transfers the client’s usage benefit to the

vendor. Thus, the client will always incur some

level of cannibalization loss when it makes investments, which will lead to lower client investment.

The intuition is that the client does not want to

work very hard making software for its competitors.

Proposition 7: The Effect of Cannibalization on Vendor Incentives. If the

net benefit to client use of the software is

[Uc(ic, ic) – *S(ic, ic)], then the possibility of

vendor overinvestment occurs under

each of the five ownership structures.

This is a slightly less intuitive result that again

follows from the fact that the vendor cannot fully

internalize the client’s usage benefit. If the vendor

could appropriate the full value of the client’s

usage benefit, then it would fully consider the

cannibalization costs. However, because it cannot, the vendor can make some investment that

benefits the vendor but harms the client.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

711

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

Table 3. Summary of Ownership Structures

Ownership Structure

Conditions That Make the Ownership Structure Second Best

Ownership structure

[(E,U), (E,U)] allows both

parties to the contract full

use of the software, but

requires that they share

the proceeds from sales

to third parties.

This ownership structure works best when three conditions hold:

(1) The usefulness of the software to each party is determined primarily

by the investments of that party.

(2) The resale value of the software is determined equally by the

investments of each party.

(3) The ability of each party to generate usefulness for itself is

approximately the same.

Ownership structure

[(E,N), (E,U)] allows the

vendor to freely use the

software, but the client

must pay for its use, and

requires that they share

the proceeds from sales

to third parties.

This ownership structure works best when five conditions hold:

(1) The usefulness of the software to the vendor is determined

primarily by the investments of the vendor.

(2) The usefulness of the software to the client depends equally on the

vendor and client’s investments.

(3) The resale value of the software is determined equally by the

investments of each party.

(4) The ability of each party to generate usefulness for the client is

approximately the same.

(5) The ability of the vendor to generate usefulness for the vendor

persists over a wide range of possible investment levels (i.e.,

returns diminish slowly).

Ownership structure

[(N,U), (E,U)] allows both

the vendor and client free

use of the software, but

the vendor keeps all of

the proceeds from sales

to third parties.

This ownership structure works best when three conditions hold:

(1) The usefulness of the software to the client is determined primarily

by the investments of the client.

(2) The usefulness of the software to the vendor is determined

primarily by the investments of the vendor.

(3) The resale value of the software is determined primarily by the

investments of the vendor.

Ownership structure

[(N,N), (E,U)] allows the

vendor to freely use the

software and grants the

vendor all of the proceeds

from sales to third parties.

Moreover, the vendor and

client share the value of

the usefulness of the

software to the client.

This ownership structure works best when all sources of value creation

depend on the vendor’s investments.

712

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

Table 3. Summary of Ownership Structures

Ownership Structure

Conditions That Make the Ownership Structure Second Best

Ownership structure

[(E,N), (E,N)] splits all

benefits equally between

the two parties.

This ownership structure works best when three conditions hold:

(1) The usefulness of the software to each party and the resale value

of the software is determined equally by the investments of each

party.

(2) The ability of the vendor to generate usefulness for the client

diminishes more quickly than the ability of the client to generate

usefulness for the client.

(3) The ability of the vendor to generate usefulness for the vendor

diminishes more quickly than the ability of the client to generate

usefulness for the vendor.

(4) The return to vendor investment in client usefulness is greater than

the return to vendor investment in vendor usefulness.

This is particularly problematic given that vendor

investment in resale is generally more important

than client investment. Vendors have the network,

the marketing channels, and the reputation to

resell useful software. Clients’ competencies

usually lie in other areas, namely, the sale of their

own products. Thus, it generally makes sense to

give excludability rights to the vendor. However, if

the vendor works too hard making the software

usable by the client’s competitors, the client may

derive little or no value from the software. This

can make the software a competitive necessity

rather than a competitive advantage (Hitt and Frei

1998).

The next proposition requires that MUc/Miv is arbitrarily large. This means that the value to the

client is highly sensitive to the vendor’s investment. Viewed another way, it means that the

vendor is very efficient at creating client value.

Presumably this is often the case, as an important

consideration of most outsourcing arrangements is

for the vendor to create value for the client.

Vendors who are not efficient at creating client

value will usually be passed over in favor of

vendors that are more efficient.

Proposition 8: Ownership Structures

to Combat Cannibalization Problems.

If the cannibalization problem is defined

to be greater when the level of * necessary for vendor overinvestment is smaller

and MUc/Miv is arbitrarily large, then the

ownership structures can be ranked from

the largest cannibalization problem to the

smallest as [(E,U), (E,U)], [(N,U), (E,U)],

[(E,N), (E,N)], [(E,N), (E,U)], [(N,N),

(E,U)].

This proposition offers guidance as to when the

cannibalization problem will be more prevalent.

The actual level of the problem depends on the

level of *, but this proposition offers guidance on

when organizations should become concerned

about the problem.

There are two basic strategies suggested by this

proposition on how to handle the cannibalization

problem. First, the parties could sign a contract

that reduces the vendor’s share of the resale

benefit. This limits vendor investment by removing

the primary incentive. However, this solution is

likely to be unappealing in practice because it is

too blunt an instrument. If, as discussed above,

vendors are more competent at resale than clients,

then removing a significant share of the resale

value from them would tend to overcorrect the

problem, causing more harm than good.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

713

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

Table 4. Summary of Cannibalization Effects

Proposition

Implication

Proposition 6: The Effect of

Cannibalization on Client

Incentives

A client will always have reduced incentive to invest in software

created in an outsourcing relationship if the use of that software

by other firms will reduce the value to the client. This occurs

because even when a client has no intellectual property rights, it

can still appropriate some value from the relationship. However,

the value is less than if there is no cannibalization issue.

Proposition 7: The Effect of

Cannibalization on Vendor

Incentives

Vendors may invest more in software created in an outsourcing

relationship than is socially optimal. This occurs because the

vendor cannot internalize the client’s loss of competitive

advantage arising from cannibalization.

Proposition 8: Ownership

Structures to Combat

Cannibalization Problems

The more intellectual property rights the client possesses, the

larger the cannibalization problem. This occurs because the

vendor internalizes less of the client’s loss of competitive

advantage as the vendor surrenders intellectual property rights to

the client.

The second strategy is to give the vendor some

share of the client’s net usage benefit via ownership. Because the vendor can never fully internalize the client’s net usage benefit, this will

always fall short of aligning vendor incentives with

total benefit. However, it does result in a move in

the right direction. Since all five basic ownership

structures promote underinvestment in the

absence of cannibalization, in the presence of

cannibalization, the additional incentive given by

client absorption of some of the costs will temper

the potential for vendor overinvestment.

The optimal strategy depends on the level of

vendor overinvestment. If overinvestment is a real

problem (* is large), then removing some of the

resale rights from the vendor will have more of an

impact on the problem. If overinvestment is a

minor problem (* is moderate), then forcing the

vendor to internalize a portion of the client net

benefit will accomplish a finer tuning of investments. If there is no overinvestment (* is small),

then the strategies discussed in the prior section

will be appropriate with no changes.

Overall, the results show that, in the presence of

cannibalization, client incentives are reduced and

714

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

vendor incentives are increased relative to the new

first best.12 The relative increase in vendor incentives may lead to vendor overinvestment. Parties

to the contract can deal with this by removing a

vendor’s excludability rights or by removing a

client’s usability rights. These ideas are summarized in Table 4.

Discussion

This work has expanded the traditional property

rights approach to consider a variety of different

ownership structures made possible by the nonphysical nature of software. Specifically, the work

proposes, illustrates, and explains how software

permits a separation of usability and excludability.

12

Vendor incentives are actually reduced or unchanged

relative to the first best without cannibalization.

However, the optimal level of investment is reduced by

more than the vendor incentives are reduced. Thus, the

vendor will make investments that are a larger

percentage (perhaps even greater than 100 percent) of

the first best under cannibalization. In the absence of

cannibalization, the vendor’s investments are a smaller

percentage of the first best level of investment.

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

This allows for one firm to hold unlimited usage

rights without requiring the other firm to surrender

any particular rights. Such a distinction requires

the property rights approach to recognize not only

the two firms explicitly involved in a relationship

but also all of the other firms implicitly in the market. This, in turn, leads to ownership structures,

such as copyleft,13 that would be nonsensical for

physical assets.

On a practical front, this work shows that the best

distribution of property rights depends on the

nature of the relationship between the two parties.

Thus, no single way to manage a relationship is

always better than any other way. The choice

between total outsourcing, partnership, incentives,

or any of the many ways to structure the relationship depends on the relative strengths and

weaknesses of the parties.

Another interesting finding is that all of the

contracts studied for motivation offered full usage

rights to clients, whereas theory suggests that a

client might want to be compensated ex ante

rather than to have property rights. One explanation of this is that negotiating power is as important

in the division of assets as value creation (Lerner

and Merges 1998). This line of reasoning suggests that firms will appropriate as many property

rights as possible, even if doing so reduces overall

surplus. Clients are certainly in a strong negotiating position prior to the signing of the contract,

and it is reasonable to believe that they use this

position to appropriate additional rights for

themselves.

This work also shows practitioners how the

possibility of cannibalization distorts the incentives

of the relationship, so that the vendor works hard

to make a technology that can be redeployed by

the client’s competitors.

Contribution

On a theoretical front, this work extends the

property rights approach (Bakos and Brynjolfsson

1993a; Bakos and Nault 1997; Brynjolfsson 1994;

Grossman and Hart 1986; Hart 1995; Hart and

Moore 1988, 1990) in order to make a number of

valuable contributions to IT literature. The thesis

of the work is that different types of assets have

different characteristics, which lead to different

potential bundles of property rights and call for

different methods of contracting for those rights.

Instead of the standard property rights model’s

physical assets, this work considers software

assets. The theory presented is based on the

actual text of real-world contracts, and takes into

account the different property rights that those

contracts exhibit.

13

Copyleft is the type of license that covers Linux. It

specifies that all agents have the right to do anything with

the software except exclude others from its use.

Finally, this work offers suggestions for what

intellectual property should be assigned in five

different situations, and how intellectual property

rights should be modified to account for cannibalization. This is extremely important to practitioners because they must actually formulate and

abide by outsourcing contracts.

Directions for Future Research

and Speculations

As with any intellectual undertaking, simply performing the process has raised new questions, and

this section speculates what some of the more

interesting questions and solutions might be.

Many of these speculations and questions

originated with reviewers.

Moral Hazard and Property Rights

One question that always arises in a research

context is, Why not some other model? Another

popular economic model for interorganizational

relationships is moral hazard (Bhattacharyya and

Lafontaine 1995). In moral hazard models, it is the

goal of the principle to choose a rule for sharing

the value of the output when the inputs are not

observable. A more recent popularization is a

multi-task model in which there are several outputs

and inputs that are more or less observable

(Holmstrom and Milgrom 1991).

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

715

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

Moral hazard type models were not used in this

work, simply because the contract sections dealing

with intellectual property, and specifically software,

did not contain sharing rules. Rather, they contained clauses assigning ownership via software

licenses. Thus, a moral hazard model would not

offer an appropriate description of the contracts

observed. Both simple moral hazard and multitask problems can degenerate into ownership

institutions if the outputs are sufficiently unobservable. However, the choice of different ownership

institutions remains. Rather than deal with the

issues of uncertainty, this work focuses on the

issues of different ownership structures. Thus, this

work offers a parsimonious model of ownership

structures without making additional assumptions

about the relative uncertainty of outcomes.

Of course, unobservability raises questions about

the ability to act on ownership structures.

However, from a practical point of view, firms must

make some estimation of the value propositions of

outsourcing, including the value of intellectual

property. The property rights approach allows

firms to take a guess at the time the contract is

written and assign the appropriate ownership

structure. The moral hazard model would require

a guess to be made at the time the output

occurred, and then to compensate the parties

based on that guess. This would be particularly

problematic in practice because there would be

great incentives to guess wrong.

The guess problem is further complicated in the

moral hazard model because no actions are left to

the parties after the guess and, thus, there is no

mechanism to insure an accurate guess. Adverse

selection problems like those of Snir and Hitt

(2004) solve this by allowing for more value creation beyond the realization of the outcome. Some

such mechanisms could be added to a moral

hazard model to insure that the guesses were

honest. However, this would further complicate

the model and still not address the central question

of different ownership structures. The property

rights approach avoids this guessing problem by

forcing renegotiation, wherein each party can

credibly commit to refuse unreasonable guesses.

While the moral hazard framework is problematic

716

MIS Quarterly Vol. 29 No. 4/December 2005

for the intellectual property part of the contract, it

may be useful elsewhere. For example, one of the

contracts requires that the project manager be

compensated based upon the outcome of a user

satisfaction survey. Such a survey avoids the

guessing problem because the individual users

have no vested interest in lying.

Generalizability

This model is based on a small number of

contracts and, therefore, questions of generalizability arise. As noted in the beginning, there is a

great deal of commonality among these contracts,

so it is not unthinkable that other contracts by the

same vendor will be similar. In practice, contracts

are generally formulated from templates, so these

contracts are probably representative of an ideal

contract that forms the basis for a number of other

arrangements. Because the vendor is large, this

may include a significant fraction of all outsourcing

arrangements. Of course, this is not proof, but

rather it is speculation that should be validated

empirically. From a practical standpoint, that may

be extremely difficult, due to confidentially issues.

As Nobel laureate Ronald Coase laments, “The

main obstacle faced by researchers in industrial

organization is a lack of available data on contracts and the activities of firms” (1992, p. 719).

Many additional directions for future research

present themselves as a result of this analysis.

Generally, these can be categorized as operational

and economic. The operational research questions are touched on briefly in some of the analysis

above. For example, the impact of IT on the ability

to contract, measure, and monitor certainly will

prove to be an interesting and valuable avenue for

inquiry (Banker et al. 2000). Researchers should

not only develop an explanation of how IT may

allow firms to write better contracts, but also how

contracts can be written to take advantage of

some of the special properties of IT, such as

costless reproduction of software. Decision support for outsourcing contracts is also an avenue of

inquiry that would help firms utilize IT to generate

value. While it seems that none are more qualified

to develop such systems than the IT community,

Walden/Intellectual Property Rights

the legal nuances of contracting would require the

cooperation of legal scholars, paving the way for

more interdisciplinary research.

Another important operational research area

concerns itself with digital contracting. Some

authors have begun to examine this issue (Dasgupta and Dickinson 1998). There is no a priori

reason why contracts must be static documents.

Contracts could be dynamic intelligent systems

that constantly update their parameters in

response to changes in the external environment.

A digital contract could have the capabilities of

smoothing the impacts of business events by

tapping directly into the accounting, finance, and

operational systems of each firm.

Another direction for future research is to expand

the range of property rights considered. This work

focuses on two different types of ownership rights

defined in prior property rights literature (Alchian

and Demsetz 1973). However, there are clearly a

multitude of different property rights that exist in

reality.14 For example, each party could have the

right to grant usability rights, so that each party

could freely sell the property to others without

gaining the acceptance of the other party. Alternatively, the software could be created with

copyleft—the ability for anyone to use the software, but for no one to sell the software. Rights

could be assigned to allow one party to exclude

some certain group and the other party to exclude

some other group—like a protected territory. The

range of possible property rights is limited only by

the creativity of the contract writer. Further

exploration of other commonly appearing rights

would certainly be a welcome contribution, as