BAD DESIGNS, LETHAL PROFITS: THE DUTY TO COLLISION RISKS

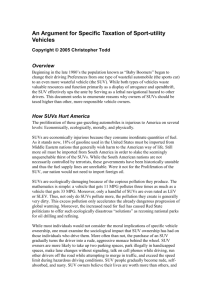

advertisement