Final Report for Two Research Studies:

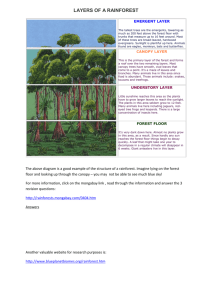

advertisement