Open Spaces as Learning Places CEMETERY UNIT

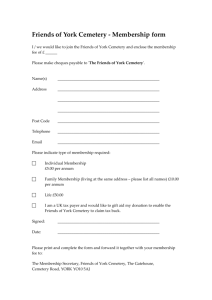

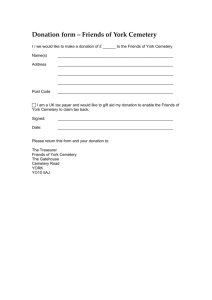

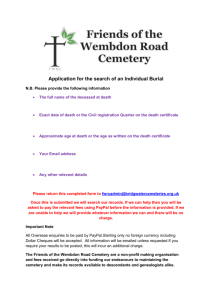

advertisement