Document 11478677

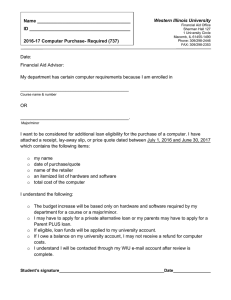

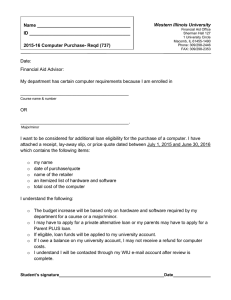

advertisement