H 5 2015 Nº

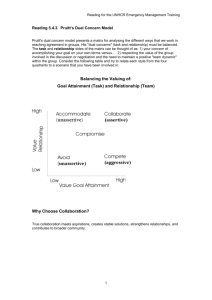

advertisement