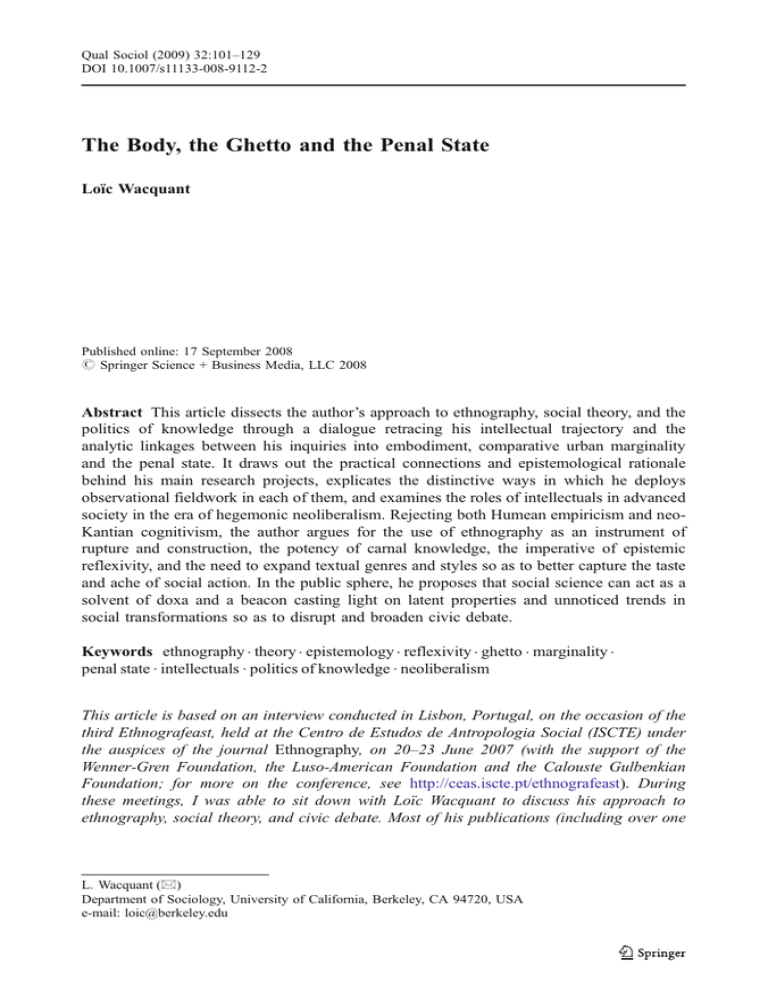

The Body, the Ghetto and the Penal State

advertisement